Open PDF in Browser: Carolina Núñez, Lucy Williams, David Wingate, Aerin Christensen, & Anna Mae Walker,* “Women’s Language” in Supreme Court Oral Arguments

“[A] girl is damned if she does, damned if she doesn’t. If she refuses to talk like a lady, she is ridiculed and subjected to criticism as unfeminine; if she does learn, she is ridiculed as unable to think clearly, unable to take part in a serious discussion: in some sense, as less than fully human.”

— Robin Lakoff[1]

In 1973, sociolinguist Robin Lakoff famously argued that female speakers use “women’s language”—a distinct set of linguistic patterns that signal tentativeness, diffidence, and powerlessness. In this Article, we test that hypothesis by identifying and analyzing gendered language patterns during Supreme Court oral arguments. We lexically analyze a corpus of more than six thousand oral arguments to identify four features of “women’s language”: hedges, super polite forms, intensifiers, and hesitation forms. We find striking evidence to support Lakoff’s hypothesis: The women in our dataset do, in fact, hedge more, hesitate more, intensify more, and use more polite forms than their male counterparts.

Our results have important implications for the study of gender, language, and the law. Since the 1970s, scholars have debated whether “women’s language” is an actual, measurable phenomenon. Our study—the first to examine “women’s language” in the Supreme Court context—suggests that it is. Our study also prompts questions about how “women’s language” affects law and the women who practice it. It is possible that “women’s language” facilitates communication, or that it is a stylistic choice that has no effect on women’s arguments, ideas, or identities. If that is true, then the patterns we observe are curious, but nothing more. But as Lakoff insisted, it is also possible that “women’s language” reflects women’s inequality and maintains women in a subordinate status. If that is so, then it is troubling to see such clear evidence of “women’s language” at the Supreme Court.

The Article proceeds in four parts. In Part I, we introduce “women’s language” and describe previous research that has explored its nuances. In Part II, we discuss our dataset and methods and describe our analysis. In Part III, we present and discuss our results. In Part IV, we explore the substantive and normative implications of our research and identify avenues for future study.

Introduction

In the 1872 case Bradwell v. Illinois, the Supreme Court held that states could deny women the right to practice law.[2] Justice Bradley’s concurring opinion explained that the Court’s decision was proper because “[t]he natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.”[3] In the 150 years since that decision, American women have proved the Court and Justice Bradley wrong.[4] Since the first woman was admitted to the Supreme Court Bar in 1879, the number of women in the legal profession has exploded. In 2023, more than half of America’s law students were women, compared to only 9 percent in 1970.[5] More than 50 percent of law firm associates are now women, compared to roughly 38 percent in 1991.[6] And whereas there were no female Article III judges for the first 138 years of American history, women now make up approximately one-third of the federal judiciary.[7] Men “still dominate the upper echelons of the legal profession,”[8] but women are now better represented in the legal field than ever before.[9]

Not surprisingly, the increasing number of women in law has prompted new research about women and law. In recent years, legal scholars have devoted new attention to reproductive rights,[10] domestic violence,[11] and other substantive legal issues that uniquely affect women’s bodies.[12] They have studied the social, political, and professional barriers that prevent women from obtaining prominent or powerful legal positions.[13] They have considered how gender affects female judges’ approach to legal issues.[14] And they have studied how female lawyers are treated in classrooms, law firms, and courts.[15]

Notably absent from these studies is any research about how women in the legal profession speak. This dearth is surprising. In nearly every other field—including business,[16] healthcare,[17] education,[18] sociology,[19] and linguistics[20]—scholars have spent considerable energy exploring how women use language to construct their social and professional identities.[21] In law, though, we know more about when and why women don’t talk[22] than about what they say when they do.

This Article begins to fill that gap by offering an analysis of the language women use during oral argument at the United States Supreme Court. Using a variety of statistical methods, we analyze a corpus of over 1.5 million conversational turns from 6,063 oral argument transcripts to identify instances of what linguist Robin Lakoff termed “women’s language”—a distinct set of linguistic patterns and tropes that convey tentativeness, insecurity, and powerlessness.[23] We focus, in particular, on four features of that discourse: hedges (e.g., “probably,” “generally,” “supposedly”), super polite forms (e.g., “thank you,” “respectfully”), intensifiers (e.g., “very,” “clearly”), and hesitation forms (e.g., pauses, stutters, “I mean”). Our analysis reveals that there are clear differences between the ways men and women speak during oral argument. Women use all four “women’s language” tropes more than their male counterparts do. Given that finding, it is not surprising that our data also show that “women’s language” has increased over time during Court arguments. After all, women are a larger share of the speakers during oral argument today than they were fifty years ago.[24] But our data suggest that something more interesting is going on. Male advocates are using more “women’s language” today than they were fifty years ago, and male Justices use more “women’s language” than male advocates do. These findings do not change the strongest dynamic we observe—that women use more “women’s language” across the board—but they do raise new questions and opportunities for discussion.

Our findings have important implications for scholarship on women, language, and the law. First, and most obviously, our results offer new insights for ongoing debates about “women’s language.” Countless scholars in linguistics and other fields have tried to determine whether Lakoff’s “women’s language” is an actual phenomenon, but previous research has reached conflicting results.[25] Our study does not resolve those inconsistencies, but it does provide new evidence for the proposition that women speak differently than men. Our study also uses advanced lexical analysis with regular expressions, which are more powerful and precise than the manual techniques “women’s language” researchers have used in the past.[26] Our analysis thus illustrates how researchers in law, linguistics, and other fields might use such methods to study unresolved questions about gender and language.

More importantly, our results prompt questions about how “women’s language” affects the law and the women who practice it. When Lakoff first conceptualized “women’s language,” she suggested that the speech patterns she described both reflect and reinforce women’s subordinate status in society. Specifically, Lakoff argued that women are taught from a young age to speak in a certain way, and when they comply, others interpret their language as “proof” of women’s subordinate role.[27] In recent years, though, some researchers have rejected Lakoff’s normative assessment and have instead argued that “women’s language” serves important communicative and persuasive functions.[28] If this latter view is correct, then the “women’s language” we observe might be a useful model for lawyers of any gender who are seeking to improve their craft. Our finding that male advocates have increasingly adopted “women’s language” is consistent with this theory. But if “women’s language” is a source and symptom of subordination, as Lakoff suggested, our findings raise some troubling possibilities. The “women’s language” we observe might, for instance, indicate that women are or feel inferior even when they are highly trained, highly educated, and operating at the pinnacle of the legal field. It might also shore up existing gender inequalities by making “women’s language” public, visible, and prominent.

These questions of gender, language, power, and law are pressing and pertinent. In recent years, the Supreme Court has dealt major blows to women’s reproductive rights.[29] Several states have enacted laws that prohibit required usage or discussion of preferred pronouns.[30] Other states have passed legislation banning transgender people from seeking gender-affirming care or from using bathrooms consistent with their gender identities.[31] And most recently, the Trump administration has declared its commitment to “defend women’s rights . . . by using clear and accurate language and policies that recognize women are biologically female.”[32] With these and other issues of gender, language, and law at the forefront of American politics, Lakoff’s hypothesis remains as relevant and troubling as it was fifty years ago. It also warrants further study and investigation because if language does, in fact, reflect and perpetuate gender and power inequities, that discovery could have important implications for how judges, lawyers, and legal academics think through and talk about contemporary legal issues.

This Article proceeds in four parts. In Part I, we introduce “women’s language” and describe previous research that has explored its nuances. In Part II, we discuss our dataset and methods and describe our analysis. In Part III, we present and discuss our results. In Part IV, we discuss the substantive and normative implications of our findings and identify avenues for future study.

Robin Lakoff and “Women’s Language”

Gender and language research is an interdisciplinary field that analyzes “the linguistic resources individuals draw on to present themselves as gendered beings” and “the discursive construction of gender and its many components through words and images.”[33] The field includes researchers from many academic disciplines, including linguistics, communications, education, business, and medicine.[34] And it encompasses a variety of methods, ranging from conversation analysis, stylistics, and discourse analysis to ethnography and corpus linguistics.[35]

One of the first and most influential scholars in gender and language research was the linguist Robin Lakoff.[36] In a 1973 article titled “Language and Women’s Place,” Lakoff famously argued that women speak differently than men.[37] Using “introspective methods”—namely, her own observations of women’s speech—Lakoff proposed that women use a distinctive “women’s language” made up of particular lexical units, syntactical rules, and intonational patterns. Specifically, Lakoff argued that women use precise color terms (e.g., “mauve” instead of “purple”),[38] avoid strong expletives,[39] and employ empty adjectives like “lovely” and “sweet.”[40] They convert declarative sentences into questions by using rising intonation.[41] Women also use tag questions (e.g., “Right?” or “Isn’t that true?”),[42] hedges (e.g., “somewhat,” “generally”),[43] intensifiers (e.g., “very,” “really”),[44] hypercorrect grammar,[45] and super polite language (e.g., “please,” “excuse me”).[46]

According to Lakoff, “women’s language” often comes across as hesitant, tentative, or trivial. For example, tag questions “give the impression [that a speaker is not] really sure of himself, . . . looking to the addressee for confirmation, . . . [or has] no views of his own.”[47] Hedges communicate diffidence and “convey the sense that the speaker is uncertain about what he (or she) is saying.”[48] Polite, profanity-free language limits a speaker’s ability to express strong emotions.[49] And precise color terms (“mauve” instead of “purple”) indicate awareness of and responsibility for trivial descriptions.[50] Taken together, the tropes of “women’s language” thus “submerge[] a woman’s personal identity by denying her the means of expressing herself strongly . . . and encouraging expressions that suggest triviality in subject matter and uncertainty about it.”[51] “The ultimate effect,” Lakoff concluded, “is that women are systematically denied access to power[] on the grounds that they are not capable of holding it as demonstrated by their linguistic behavior.”[52]

Since the 1970s, dozens of scholars have tested, challenged, extended, and complicated Lakoff’s hypothesis.[53] Some have questioned whether the linguistic patterns Lakoff observed stem from gender or from something else—social status,[54] age,[55] culture,[56] relational factors,[57] personality factors,[58] self-conception about sex roles, and more.[59] Others have analyzed the effects of gendered language patterns by considering whether so-called “women’s language” affects a speaker’s persuasiveness,[60] attractiveness,[61] or ability to exert social influence.[62] A few have questioned Lakoff’s description and identification of “women’s language” tropes, noting that linguistic forms like hedging and tag questions can “serve different ends across different sociolinguistic contexts.”[63] Some have engaged with the normative implications of Lakoff’s hypothesis, arguing that gendered language patterns—if they exist—reflect differences but “do not involve deficiencies.”[64] And many have used empirical methods (as opposed to Lakoff’s “introspective” technique[65]) to test the hypothesis that men and women speak differently.[66]

Scholars have likewise refined, applied, and extended Lakoff’s ideas into the legal field. For example, in one of the earliest and most influential studies to test Lakoff’s hypothesis, William O’Barr and Bowman K. Atkins used ethnographic methods to analyze “women’s language” in North Carolina trial courts.[67] They discovered that some women used “women’s language” more than others and that men occasionally used it, too.[68] They also observed that the speakers who used “women’s language” most frequently tended to occupy a lower social status.[69] The authors thus determined that “so-called ‘women’s language’ is neither characteristic of all women nor limited to only women.”[70] Rather, “the variation in [‘women’s language’] features may be related more to social powerlessness than to sex.”[71]

Legal scholars have also considered the effects of “women’s language” in various legal contexts. They have used surveys and experiments to determine whether “women’s language” (or “powerless language,” to use O’Barr and Atkins’s terminology) affects perceptions of credibility or blame in courtroom proceedings.[72] They have studied the effects of “women’s language” in different types of legal writing, including wills,[73] appellate opinions,[74] and briefs.[75] They have considered how “women’s language”—if it exists—affects speakers’ ability to access procedural justice or exercise rights that must be invoked verbally, like the Fifth Amendment rights to counsel and silence.[76] And they have generally examined how “women’s language” affects courtroom and client interactions.[77]

Surprisingly and disappointingly, this vast literature has yielded few clear insights about “women’s language.” Scholars disagree about how to identify and measure the tropes of “women’s language” in the first instance.[78] They also disagree about the normative significance of gendered language patterns. Though some maintain that “women’s language” is a marker of tentativeness or submission,[79] others suggest that the tropes of “women’s language” might actually be powerful linguistic techniques that women use to express interpersonal solidarity,[80] articulate care or concern,[81] or fulfill other important functions.[82] Perhaps most significantly, academics disagree about whether the phenomenon of “women’s language” actually exists: Though many studies suggest that women do, in fact, use the linguistic features Lakoff identified,[83] others have found that men are more likely to use those features,[84] or that there is no relationship at all between gender and language patterns.[85] In short, notwithstanding fifty years of scholarly pursuit, “[i]t is now apparent that, if they do exist, gender differences in hedging [and in language overall] are subtle and subject to marked variation across speakers and contexts of use.”[86]

In what follows, we revisit Lakoff’s simplest, original hypothesis—namely, that women speak differently than men. More specifically, we use lexical analysis to identify and analyze the tropes of “women’s language” in a new context: oral arguments at the United States Supreme Court.[87] Our study, which we describe in Part II below, is the first to investigate “women’s language” in the Supreme Court context.[88] It is also the first to use statistical lexical analysis to analyze “women’s language” in the law. Our work thus offers new and novel insights about whether and how Justices and advocates at the nation’s highest Court use “women’s language.” It also illustrates how future legal researchers might use similar analytical techniques to study more nuanced questions about language, gender, and power.

Measuring “Women’s Language” In Supreme Court Oral Arguments

Data

Our study relies on a corpus of Supreme Court oral argument transcripts from 1955 to 2024. We created this corpus using transcripts from Oyez.org, a multimedia archive that provides transcripts, synchronized and searchable audio, case summaries, and full-text opinions for nearly every Supreme Court case. Though similar transcripts are available on the Supreme Court’s website, we used Oyez because it covers more years of Supreme Court argument: The Supreme Court’s official archive begins in 1968, whereas Oyez begins in 1955. The Oyez transcripts also identify the speakers who participated in each oral argument—something that official Supreme Court transcripts did not do until 2004.[89]

The Oyez transcripts from 1980 to the present are based on the same official Court transcripts that are available on the Supreme Court’s website.[90] For terms prior to 1980, Oyez used outsourced labor to generate the transcripts from audio recordings of oral argument.[91] In our communications with Oyez, a representative noted that poor-quality source audio occasionally made it difficult for the Oyez team to accurately transcribe the arguments and speaker identities, “though the extent of the inaccuracies is challenging to measure.”[92] Notwithstanding these shortcomings, the Supreme Court’s website lists Oyez alongside Westlaw, Lexis Advance, the National Archives, and ProQuest as a place where researchers can access oral argument transcripts.[93] We thus feel confident that the Oyez transcripts are an accurate and reliable source for our study.

Transcripts provided by Oyez are organized by docket number. Each case is then separated into conversational turns, or continuous segments of speech attributed to different speakers. Each turn is annotated with pointers to the relevant audio recording, and is attributed to a single speaker, along with some metadata about the speakers’ role (either as a Justice or as an advocate).

To preprocess the data, each conversational turn was annotated with year, docket number, current speaker, current speaker’s gender, previous speaker, previous speaker’s gender, and the “relative year” of service of the current speaker.

Oyez does not provide the gender of the speakers. To determine the gender of each of the speakers, we analyzed each name using the GPT-4o language model from OpenAI. GPT-4o, drawing on its training data (which includes publicly available data, proprietary data, audio, video, and code), coded each name with a gender.[94] Though the oral argument transcripts may have been part of GPT-4o’s training data, we did not provide those transcripts when we provided the speakers’ names, and we did not prompt GPT-4o to consider the transcripts when assigning gender. However, we did provide some context about the speaker in question, telling GPT-4o that it was someone who argued before the Supreme Court, with the date and title of the case. Finally, we allowed GPT-4o to respond with “unknown” as the gender; in those cases, manual human annotation was used to assign gender.[95]

In total, our corpus contains transcripts from 6,063 cases. It includes 66,102,723 words spoken across 1,512,720 conversational turns by 8,833 different oral argument speakers. Eighty‑nine percent of our corpus consist of turns spoken by men; 9 percent spoken by women, and 2 percent with an unknown gender.

Coding “Women’s Language”

Lakoff’s original essay identified at least twelve features of “women’s language.”[96] These include:

- Hedges (e.g., “It seems to me that . . . ,” “I’m not sure I agree . . . .”)

- Super polite forms (e.g., “If you don’t mind . . . ,” “Could you please . . . .”)

- Tag questions (e.g., “It’s nice here, isn’t it?”)

- Intensifiers, or “speaking in italics”[97] (placing emphatic stress on words like “very,” “super,” and “so”)

- Empty adjectives (e.g., “cute,” “lovely,” “divine”)

- Hypercorrect grammar and pronunciation

- Lack of humor

- Heavy use of direct quotes

- Precise color terms (e.g., “mauve” instead of “purple”)

- Rising intonation on declarative statements (e.g., “I don’t agree?”)

- Hesitation forms (e.g., “um” and repeated words)

- Avoidance of strong swear words

Of these twelve tropes, we analyze four: (1) hedges, (2) super polite forms, (3) intensifiers, and (4) hesitation forms. We selected these tropes because they routinely occur during oral arguments and are readily identifiable in written transcripts. We omitted the remaining eight tropes because they are either irrelevant or absent during oral argument or because they are difficult to identify using lexical methods. For example, four of the tropes we omitted—hypercorrect grammar, empty adjectives, precise color terms, and avoidance of strong swear words—are either absent or irrelevant during oral argument. Supreme Court arguments are formal and professional proceedings, so participants tend to avoid both profanity and frivolous words. All participants are highly educated and hyper prepared, so they generally use grammar that is precise and correct. And because oral arguments are often highly technical discussions of law, there are rarely reasons for participants to use color terms. We thus expected to see little variation in any of these “women’s language” features.

We also excluded tag questions and direct quotations, because both take on different meanings in oral argument than in ordinary speech. In day-to-day conversation, tag questions and direct quotes might indicate diffidence or insecurity.[98] In an appellate argument, though, parties routinely quote caselaw, statutes, and legal briefs to establish the authority of their positions. And while advocates rarely ask questions of the Justices, Justices always (if not exclusively) ask questions of the advocates, and they often do so using the tag-question form.[99] Analyses of tag questions and direct quotes are thus likely to yield skewed or misleading results. Because of this, we excluded both from our study.

Finally, we excluded tropes that are difficult to identify or analyze using lexical analysis. Humor is subjective, and laughter generally does not appear in oral argument transcripts. Intonation likewise is not detectable in written transcripts.

These exclusions limit our ability to draw conclusions about “women’s language” broadly. However, there are many existing studies that focus on just one or two “women’s language” tropes.[100] Our analysis thus offers more breadth than many prior analyses. Further, our study is the first to analyze “women’s language” in Supreme Court oral arguments. If it is narrow, it nonetheless provides novel insights about gendered language patterns in the nation’s highest Court.

In the remainder of this Section, we explain the technical decisions we used to identify hedges, super polite forms, intensifiers, and hesitation forms in Supreme Court oral argument. In the following Part III, we present our analysis.

Hedges

Hedges are words or phrases that “make language less definite”[101] and “convey the sense that the speaker is uncertain about what he (or she) is saying, or cannot vouch for the accuracy of the statement.”[102] Hedges also distance speakers from their assertions and make a speaker’s claims less susceptible to falsification because it is difficult to challenge a statement that a speaker has cabined from the outset.[103]

In 2012, Rachael Hinkle conducted a study of more than fifty hedges in judicial opinions.[104] Our study borrows from Hinkle’s list, but we use only those hedges that seem most likely to appear in oral argument. Additionally, we include hedges that appeared during our preliminary review of the oral argument transcripts. We include all possible tenses and variations of each word—for example, “approximate” and “approximately”; “seem,” “seems,” and “seemed,” and so on. In total, our analysis includes 107 hedges, which we list in the footnote below.[105]

Super polite Forms

Super polite forms are words or phrases a speaker uses to convey politeness and propriety.[106] According to Lakoff, women use super polite forms because “women are the repositories of tact and know the right things to say to other people.”[107] Further, women are expected to conform to societal rules—including rules about civility and politeness—and they suffer social consequences (more so than men) when they stray from those conventions.[108]

Any word or phrase that is traditionally used to convey formality or deference qualifies as a super polite form. Lakoff specifically identifies two: “please” and “thank you.”[109] But Lakoff also acknowledges that super polite forms may vary across contexts and cultures.[110]

For this study, we identified eleven polite forms that are particularly likely to appear in the context of oral argument: “thank you,” “thanks,” “I appreciate,” “please,” “excuse me,” “would like,” “have to,” “could,” “my friend,” “sorry,” and “respectfully.” We omitted the polite form “your honor,” because it is essentially required during oral argument: By convention, advocates always address Justices as either “Justice” or “your honor.” Further, only advocates use the term “your honor”; Justices never refer to themselves or others that way. Thus, the frequencies of “your honor” would be inevitably skewed toward advocates.

Intensifiers

Intensifiers—words like “clearly,” “obviously,” and “so”—“intensif[y] the meaning of the word or phrase that [they] modif[y].”[111] In her original article, Lakoff posited that intensifiers are signs of tentativeness and powerless because they allow speakers “a way of backing out of committing oneself strongly to an opinion.”[112] More recently, scholars have suggested that intensifiers convey insecurity because they “are used to cover up a lack of logical proof”[113]—that is, speakers turn to intensifiers when they have no other support for their claims.[114]

For this analysis, we focused on the same twelve intensifiers that Long and Christensen included in their 2008 study of intensifiers in appellate briefs: “very,” “obviously,” “clearly,” “patently,” “absolutely,” “really,” “plainly,” “undoubtedly,” “certainly,” “totally,” “simply,” and “wholly.”[115] We also coded for five of the intensifiers included in Bradac, Mulac, and Thompson’s 1995 study of intensifiers in small group problem-solving conversations: “completely,” “definitely,” “extremely,” “fully,” and “quite.”[116] We selected these intensifiers because they have previously been studied in the legal context, seem particularly likely to appear in Supreme Court oral arguments, or both. We excluded other intensifiers that are colloquial, slang, or vulgar and therefore less likely to be present in our dataset.[117]

Hesitation Forms

Hesitation forms are any language pattern that causes a disruption in the flow of speech.[118] These include pauses, self‑repetitions, stutters, filler words (e.g., “um,” “ah,” “eh”), and meaningless small words (e.g., “you know,” “oh,” “well,”

“let’s see”).[119] Like other tropes of “women’s language,” hesitation forms are thought to make speakers seem less confident and credible, regardless of the content of their speech.[120]

Our study analyzes one type of hesitation form: meaningless phrases.[121] We focus on meaningless phrases because oral argument transcripts are inconsistent in whether and how they record filler words like “um” and “eh.” They are also inconsistent in how they record pauses and self-repetitions. Sometimes these hesitation forms are transcribed as either “—” or “. . . ,” sometimes they are written out, and sometimes they are not transcribed at all.[122] Because of these inconsistencies and variations, we chose not to include self-repetitions, pauses, and filler words in our analysis.

To measure meaningless phrases, we selected nine words and phrases that other scholars have used in their research on hesitation forms. From O’Barr and Atkins’s 1980 study of trial transcripts, we included: “oh,” “well,” “let’s see,” “now,” and “so.”[123] And from Boonsuk, Ambele, and Buddharat’s 2019 study, we included: “I think,” “I mean,” “you know,” and “you see.”[124]

Methods

The tropes we have identified are defined by specific sets of words and phrases that can be easily identified in argument transcripts. This suggests a straightforward technical strategy: Instead of a semantic analysis of the meaning of arguments, we instead opt for an analysis of the specific words used by specific speakers. This is known as “lexical analysis”; a semantic analysis of our data is possible but is beyond the scope of this Article.[125]

Detecting tropes in transcripts is a straightforward programming task. We analyzed the transcript associated with each case by identifying each speaker’s conversation turns—that is, the continuous segment of text attributed to that speaker before another speaker begins or the transcript ends. We then searched the text of each turn for each trope word. We counted the number of occurrences of each trope word and attributed that count to the trope word’s corresponding category. Searching was accomplished using standard regular expressions (a basic pattern‑matching technique that allows us to account for variations on a base lemma), with some lightweight text preprocessing. This was all automated with a single analysis script to avoid any human-introduced error. Finally, the category counts were attributed to individual speakers via the metadata provided by Oyez.

However, not all Court participants speak for equal amounts of time—there are significant differences between the number of words spoken by different speakers, with some only contributing a few hundred words to an argument, while others may contribute thousands. To compensate for the variability in per-speaker word counts, we centered our analysis on the rate at which a given speaker uses women’s tropes. This rate was calculated by counting the number of trope words used by a speaker divided by the total number of words used by a speaker.

Any individual speaker (either Justice or advocate) may participate in multiple cases before the Court in any given year. Preliminary analysis (not included in this Article) suggested that the rate of trope usage changes over the course of an individual’s career. For both of these reasons, we opted to calculate trope rates by aggregating counts on a per-year basis.

Our data therefore consists of tuples of (year, speaker, gender, role, trope rate); any given speaker may appear multiple times in our dataset. The “role” data is provided by Oyez and indicates an individual’s role at the time the case was argued. Certain individuals (such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg) argued cases before the Court as an advocate before joining as a Justice, and therefore appear in our data multiple times with multiple different roles.

Results

In this Section, we catalogue and explore our results. We first provide a high-level visualization of our data’s overall quantity and distribution across time. We then compare “women’s language” usage by gender and role, in the aggregate and across time. Our analysis reveals five striking patterns.

First, our analysis shows that “women’s language” exists in Supreme Court oral arguments: On average, female speakers in our dataset hedge more, hesitate more, intensify more, and use more super polite forms than their male counterparts. Second, these usage patterns exist regardless of the speaker’s role: Female Justices use more “women’s language” than male Justices, and female advocates use more “women’s language” than male advocates. Third, we observe that “women’s language” usage has increased over time for men and women participating in oral arguments.

Our fourth finding is that Justices use “women’s language” more than advocates do: Male Justices and female Justices use “women’s language” more than male advocates and female advocates, respectively. Fifth, and perhaps most interestingly, male Justices’ trends in their “women’s language” usage parallel female Justices’ usage trends. That is, when “women’s language” increases among the female Justices, the same occurs in the male Justices’ rate of usage.

In the remainder of this Section, we elaborate on each of these findings in the course of discussing (1) our dataset as a whole, (2) speaker gender and corresponding rates of “women’s language,” (3) speaker role and corresponding “women’s language” rates, and (4) historical trends in Justices’ and advocates’ rates of “women’s language.” Throughout our discussion, we also explore possible explanations for the unexpected patterns we observe, mindful of our methodology’s limits and inability to identify causal relationships. This provides context for the implications we examine in Part IV below.

Overview of Total Conversation Turns

As noted above, our corpus of oral argument transcripts includes over sixty-six million words spoken by 8,833 unique speakers. Figure 1 provides an overview of speakers’ conversation turns over time. A conversation turn is a continuous segment of text attributed to a single speaker before another speaker begins or the transcript ends. A conversation turn may be as short as an advocate saying “Yes, Your Honor” or a Justice asking a question. A conversation turn may also represent several minutes of oral argument that stops upon interruption by a Justice. In other words, conversation turns do not represent the volume of words used in oral argument; rather, they help illustrate the dynamic exchange of arguments and questions that takes place. In an argument where Justices interrupt often or pepper advocates with questions, there will be many conversation turns because the argument rapidly shifts from one speaker to another. By contrast, in a slower argument where Justices have few questions or allow advocates to speak for longer intervals without interruption, the number of conversation turns will be low.

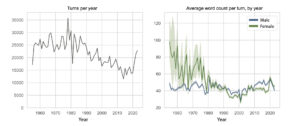

We depict the conversation turns by year on the left side of Figure 1. As illustrated there, conversation turns generally hovered between twenty thousand and thirty thousand from 1960 till the early 1990s, with a few exceptions in the late 1970s and 1980s. As reflected in Figure 1, there were over thirty-five thousand conversation turns in 1978 and under eighteen thousand conversation turns in 1981. It is unclear what drove the spike and subsequent drop; the trend does not correspond with any reduction in the number of cases decided by the Court in those years.[126] There is a clear correlation, however, between the decrease in conversation turns that begins in the early 1990s and the decrease in the number of Court decisions made since then. As the Court has reduced its docket, the number of conversation turns each year has, not surprisingly, fallen.[127] We observe a sharp spike in 2021 that might reflect the addition of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Court and changes to oral argument format. Commentators have noted that Justice Brown Jackson is a particularly active participant in oral arguments and often speaks more than her predecessor, Justice Stephen Breyer.[128] But the magnitude of the spike most likely relates to significant changes in the format of oral arguments during that time period. When the Court returned to in-person hearings after the pandemic, the Justices resumed their pre-pandemic practice of interrupting advocates’ arguments to ask questions and, in addition, continued the pandemic-era practice of each Justice taking turns to ask questions at the conclusion of the advocates’ argument.[129] On the right side of Figure 1, we plot the average number of words spoken in a single conversation turn by gender; we see that before about 1985, women’s conversation turns were longer than men’s, perhaps reflecting Justices making fewer interruptions to women’s arguments. After 1985, the dynamic changed. The length of speaking turns for men and women are much closer, with men’s speaking turns slightly longer, on average, than women’s.

Figure 1. Conversation Turns and Average Word Length by Year[130]

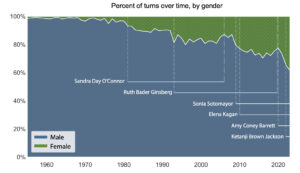

Figure 2, below, depicts the proportion of conversation turns spoken by women (green) and by men (blue) during oral arguments. This Figure includes all conversation turns, whether by advocates or Justices. The most obvious trend to note is the increase in female conversation turns over time.

In the early years of our dataset, female oral argument participants had few conversation turns relative to male participants. Indeed, in 1955, the first year of our dataset, less than 1 percent of conversation turns are attributed to women. This is consistent with historical records of those early oral arguments. In the 1957 volume of the Journal of the Supreme Court of the United States, which catalogues the details of all cases considered by the Court, we find only three cases in which women argued before the Court.[131] This is unsurprising: From 1950 to 1970, less than 5 percent of attorneys in the United States were women.[132]

Over time, however, the proportion of female conversation turns has gradually increased, rising to account for more than one-third of all conversation turns in 2024. This increase parallels the overall rise in female attorneys and judges in the United States[133] but, interestingly, outpaces the increase in oral arguments made by women at the Supreme Court over the same time period. While women were responsible for just over 15 percent of oral arguments during 2015,[134] more than 20 percent of conversation turns for that year were by women. There are many possible explanations for this. As examples, female Justices’ conversation turns might account for the gap, or interruptions to women’s arguments or questions may result in more—but shorter—conversation turns for women.[135]

The vertical dashed lines in Figure 2 mark the confirmation years of each female Justice (also annotated are the years when Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg left the Court). There is a clear inflection point in the proportion of female conversation turns at the year of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s confirmation. Some of that increase is quite likely due to the introduction of Justice O’Connor’s conversation turns during oral argument. Some may reflect the rapid increase in the number of female attorneys during the 1990s: While the total number of women lawyers in the United States increased from 3 percent to 8 percent between 1970 and 1980, that number increased from 8 percent to 20 percent between 1980 and 1991.[136]

Figure 2. Conversation Turns by Gender Over Time[137]

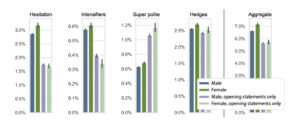

Comparing “Women’s Language” Usage by Speaker’s Gender

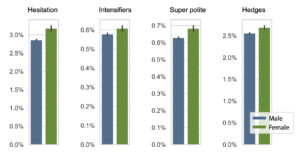

Figure 3 depicts men’s and women’s average rates of usage for each “women’s language” trope per oral argument and provides a visual comparison of the averages for men and women for each trope. As the Figure shows, female oral argument participants used each of the four “women’s language” tropes more frequently than male oral argument participants,[138] even accounting for the uncertainty range.[139] This result is noteworthy. As we explained above, past studies of “women’s language” have disagreed about whether and to what extent “women’s language” exists.[140] But our study, the first analysis of “women’s language” in the Supreme Court context, provides support for Lakoff’s hypothesis that women and men speak differently. At least during oral argument, women seem to hedge more, intensify more, hesitate more, and use more polite forms than male participants, and they do so more than men at a consistent rate across all tropes.

Figure 3. Average Rate of Usage of Each “Women’s Language” Trope, by Gender[141]

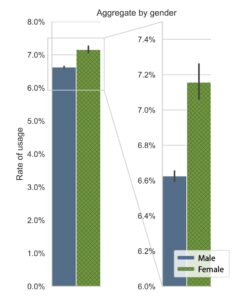

Figure 4 below represents the aggregated comparison of female speakers’ and male speakers’ “women’s language.” As shown in the Figure, women’s rate of “women’s language” is more than half a percentage point higher than men’s. Put in relative terms, women’s rate of “women’s language” usage is 108.3 percent of men’s. This is not surprising, given the consistent pattern observed in each individual trope throughout the dataset.

Figure 4. Average Rate of Usage of All “Women’s Language” by Gender[142]

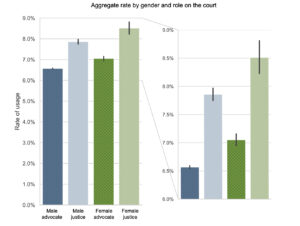

Comparing “Women’s Language” Usage by Role

As discussed in Part I above, some past researchers have suggested that “women’s language” might be a function of a speaker’s relative power rather than a function of gender. O’Barr and Atkins, for example, found that in their study of trial courtrooms, “powerful” speakers (i.e., speakers who have high social standing or special status in the court) used “women’s language” less frequently than “powerless” speakers.[143] To explore this possibility, we separated our data by speaker role: advocate and Justice.[144] Figure 5 depicts this division. The colored bars represent the average rate of usage per oral argument for each of four categories: male advocate, male Justice, female advocate, and female Justice.

As the Figure shows, within each role, men use “women’s language” less than their female counterparts do. That is, male Justices use “women’s language” less than female Justices do, and male advocates use “women’s language” less than female advocates do. This result is consistent with Lakoff’s hypothesis that “women’s language” varies by gender. This result also casts some doubt on O’Barr and Atkins’s competing power hypothesis. Among Justices, there is no significant difference in power as social standing: All Justices have elite academic credentials, all were nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, and so on. And though advocates may have different social statuses, they nonetheless enjoy the same status before the Supreme Court. In short, there is no meaningful variation in power in either the Justice group or the advocate group. And yet, we continue to see gendered differences in “women’s language” usage within each group. If power, rather than gender, explained “women’s language” usage, we would expect no variations in “women’s language” where, as here, power is held relatively constant. That gender variations persist even after we control for power (by separating our dataset by role) suggests that gender has some effect on speech patterns.

Our findings cast further doubt on O’Barr and Atkins’s argument by revealing a second, unexpected dynamic. When we compare “women’s language” usage across roles, rather than across genders, we see that Justices use more “women’s language” than their advocate counterparts. That is, female Justices use “women’s language” more than female advocates do, and male Justices use “women’s language” more than male advocates do. If O’Barr and Atkins’s power hypothesis were correct, we would expect to see the opposite result: Advocates, the less powerful party in an oral argument, would use more “women’s language” than Justices. Our contrary finding thus undermines the idea that “women’s language” is related to power rather than gender, at least at the Supreme Court. If anything, our results suggest that a contrary dynamic is at play: “Women’s language” may correlate with higher relative standing in an oral argument.

Figure 5. Average Rate of Usage of All “Women’s Language” Usage Per Oral Argument by Role and Gender[145]

It is difficult to explain why a higher status—that of Justice—might correlate with increased use of “women’s language.” It is possible that this dynamic is merely an artifact of high‑stakes litigation at the Supreme Court. Only a small percentage of attorneys in the United States have argued or will ever argue before the Supreme Court,[146] and the results of a Supreme Court case are significant to the litigants and to the country at large. As a result, advocates spend an enormous amount of time preparing for oral argument. By the time advocates argue before the Court, they have spent weeks refining and rehearsing, often in front of a panel of other attorneys who raise questions they believe the Justices are likely to ask. Thus, an advocate’s oral argument, including responses to questions, is highly polished.

Further, across the board, “women’s language” tropes are not associated with the confidence and assertiveness that public speaking guides encourage.[147] Lakoff herself denigrates “women’s language” in her initial writings about the phenomenon, suggesting that it “relegate[s] women to certain subservient functions” and makes it appear that women are “unable to speak precisely or to express [themselves] forcefully.”[148] It is no surprise, then, that advocates of all genders might practice, edit, and rehearse to deliberately avoid “women’s language” in their arguments.

To explore whether the rehearsed nature of the advocates’ oral arguments might help explain the difference between advocates’ and Justices’ use of “women’s language,” we isolated every conversation turn that begins with “May it please the Court.” We assume these conversation turns, which we will call “opening statements,” are the beginning of an advocate’s oral argument and are highly rehearsed and possibly memorized. These conversation turns are not responses to Justices’ questions and represent the advocate’s attempt to set the tone for her or his argument.

Our results provide evidence that rehearsed conversation turns contain less “women’s language” than more spontaneous conversation turns. Figure 6 depicts individual “women’s language” trope usage in male and female opening statements and in the rest of oral argument. We see that both men and women use significantly fewer hesitations and intensifiers during their opening statements than they do across all oral argument speech. In fact, the rate for hesitations and intensifiers in opening statements for both male and female advocates is about half the rate across all oral argument. Notably, female advocates use intensifiers less in opening statements than their male counterparts do: This is the only instance where we see male advocates use more “women’s language” than female advocates even when accounting for uncertainty ranges. Because of the rehearsed nature of opening statements, we speculate the higher rate of intensifiers in male advocates’ opening statements represents an intentional choice meant to persuade or show confidence. However, we cannot explain why women would not also choose to use as many intensifiers in their opening statements.

For super polite forms, we see a different result: Advocates, regardless of gender, appear to use more super polite forms in opening statements than across all oral argument. Because opening statements follow rigid formality norms that involve a high number of super polite terms (for example, “May it please the Court”—the very phrase we used to identify opening statements—includes a super polite form), we do not find this result meaningful. For hedges, the rates are nearly the same in opening statements and across all speech for both female and male advocates. As with super polite forms, we do not assign much meaning to that result. Opening statements often include broad overviews of legal doctrine because advocates are trying to introduce their arguments quickly and succinctly. It makes sense, then, that advocates would use terms like “generally” and “usually” at the beginning of their presentations.

Figure 6. Average Rate of Usage for Each “Women’s Language” Trope in Opening Statements by Gender[149]

Justices’ participation in oral argument differs dramatically from that of the advocates. Justices’ questions and interjections are less likely to be rehearsed and polished in a way that eliminates “women’s language” tropes. Though Justices surely have topics and themes they would like to explore during oral argument, their questions are often contemporaneous reactions to something the advocate has said rather than a practiced segment of speech. Justices’ conversation turns, then, are not the same as advocates’ conversation turns. One might conclude that the two are not good candidates for comparison and that our finding that the Justices use “women’s language” more than their advocate counterparts holds little meaning. But before drawing that conclusion too hastily, it is worth considering that the very difference between advocates’ and Justices’ speech during oral arguments points to a power dynamic. Justices are not subject to the same pressures to polish and prepare for oral argument precisely because they wield the power in the Court. The reverse is true; advocates must polish and prepare precisely because they are subject to the Justices’ power to decide the case. Supreme Court oral arguments may provide a highly visible example of how power and status are counterintuitively associated with the usage of “women’s language,” and this larger dynamic may play out in other contexts that our methodology could help us explore.

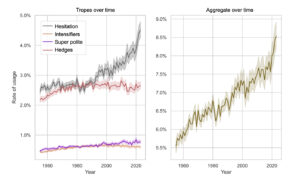

Exploring Historical Trends

Thus far, we have observed clear gender-associated and role-associated patterns in the use of “women’s language” across our entire dataset. We now turn to the historical trajectory of “women’s language” at Supreme Court oral arguments.

Figure 7 below provides a bird’s-eye view of “women’s language” historical trends in oral argument. The right panel, which represents all “women’s language” usage, shows a distinct trend of increasing usage. This is hardly surprising, given the historical increase in female conversation turns during oral arguments[150] and in light of our finding that women use more “women’s language” than their male counterparts do.[151] The participation of more women, who generally use more “women’s language,” should indeed result in increasing “women’s language.” The left panel breaks out the data by individual trope and shows that much of the upward trend is due to increasing hesitation.

Figure 7. “Women’s Language” Usage Over Time[152]

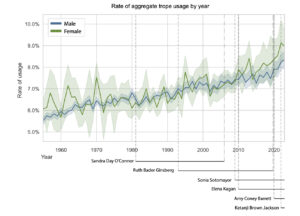

Figure 8 below adds an unexpected twist to our result. Figure 8 depicts “women’s language” usage by men and women over time. The overall upward trajectory of this Figure parallels the trend we saw in Figure 7. But the fact that both men and women have started using increasingly more “women’s language” during oral argument is unexpected. That is, the increase we see in Figure 7 is not entirely attributable to the increase in female conversation turns and female speech during oral arguments. Men are also using “women’s language” tropes more and more.

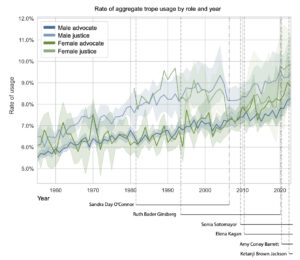

Figure 8. “Women’s Language” Usage, by Gender, Over Time

To further understand the increase in “women’s language,” we separated the data by both role and gender and plotted it across time in Figure 9, below. Consistent with Figures 7 and 8, the overall trend remains largely the same. Advocates and Justices, whether male or female, are using more “women’s language” today than they were in the past. Figure 9, however, reveals that advocates’ use of “women’s language” has increased gradually and relatively evenly when compared to the Justices’ use of “women’s language.”

As seen in Figure 9, the average rate of “women’s language” usage for female Justices and male Justices has several sharp increases and drops. We expected this result for female Justices. We know that female Justices use, on average, more “women’s language” than male Justices do,[153] and the number of women on the Court has historically been small, which amplifies the effect of each addition or retirement to the female Justice’s ranks. The retirement of a female Justice can cut the number of female Justices in half, as it did with the retirement of Justice O’Connor in 2006. Likewise, the appointment of two female Justices in rapid succession can triple that number, as occurred with the appointments of Justices Kagan and Sotomayor in 2009 and 2010. Indeed, we see a drop in female Justices’ rate of “women’s language” in 2006 when Justice O’Connor retired, and increases when Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, Coney Barrett, and Brown Jackson joined. The only counterexample of the general pattern of more female Justices correlating with more “women’s language” by female Justices is a drop after the appointment of Justice Ginsburg. While we did not divide out “women’s language” rates for each Justice, we suspect the drop might be driven by an unusually low rate of “women’s language” from Justice Ginsburg.[154]

What we did not expect from analyzing the trends by gender and role was that male Justices’ use of “women’s language” would generally parallel that of the female Justices. The trend for male Justices includes similar increases and drops that coincide with those of the female Justices. While our methods do not allow us to make causal inferences, it is hard to ignore that these parallel trends have significant inflection points at the year of female Justices’ appointments and retirements. Beginning in 1981, after Justice O’Connor’s appointment, male Justices’ “women’s language” increased and hovered well above where it had been prior to Justice O’Connor’s appointment. Joint increases occurred during several other years as well—in 2010 and 2011, which correspond with the appointments of Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, and in 2020, which corresponds with the death of Justice Ginsburg and the appointment of Justice Barrett. And at Justice O’Connor’s retirement in 2006, we observe sharp decreases in both the female and male Justices’ rate of “women’s language.” In short, when female Justices’ rate of “women’s language” rises or drops, it appears that male Justices’ rate often does the same.

There are also tandem inflection points in male and female Justices’ “women’s language” in years that do not correspond with appointments or retirements. For both female and male Justices, we observe coinciding peaks in 1989 and valleys in 2015. This is not to say that there aren’t instances in which male Justices increase their rate of “women’s language” while female Justices decrease their rate, or vice versa. We see an example of contrary inflection in 2001, when male Justices’ rate of “women’s language” increased at the same time female Justices’ decreased. But the instances of contrary inflection are fewer and less dramatic than the overall comparable trends.

It is curious that male and female Justices’ use of “women’s language” seems to increase and decrease in tandem. If these parallel trends were more subtle and less variable, like the trends for male and female advocates, we might attribute the phenomenon to a general pattern of increasing “women’s language” usage during oral argument. But that is not the case. While our data cannot tell us the cause of the phenomenon, we offer a few possible explanations.

Figure 9. “Women’s Language” Usage by Gender and Role Over Time[155]

One possibility is that Justices mirror each other’s language. Numerous studies document the human tendency to subconsciously mirror each other during conversation. Humans mirror each other’s speech patterns, tone, facial expressions, and body movements.[156] Sometimes called the “chameleon effect,” mirroring can help individuals establish rapport with each other because it communicates shared sentiments, empathy, and equal social status.[157] In experiments, people who feel excessively dissimilar from an important group often mimic that group.[158] The reverse is also true: Existing rapport can result in more mirroring during interactions.[159]

A natural human dynamic, then, may play a role in the similar trends we see in female and male Justices’ “women’s language,” with Justices subconsciously adopting each other’s speech patterns to build rapport. At first blush, though, our data suggest that this mirroring is gendered in a counterintuitive way. Why would eight male Justices significantly increase their “women’s language” usage when one female Justice joins the Court? If anything, it seems more plausible that the Justice who is in the minority—the female Justice—would adopt the language patterns of the majority. But without data on how the Justices speak outside of oral argument (i.e., without knowing whether and how they use “women’s language” in ordinary conversation), we cannot speculate as to whether there is a gendered dynamic to mirroring among the Justices. It may be that female Justices are indeed mirroring their male counterparts and that their “women’s language” usage is less than it would otherwise be during oral argument. A historical analysis of “women’s language” on a Court that starts out with a majority‑male bench but later becomes a majority-female bench may offer clues.

Of course, there are likely many other explanations for the parallel patterns we observe over time, including the idiosyncrasies of one or two Justices. We do not map out the appointment of male Justices in this study, but if a particular male Justice uses significantly more “women’s language” than the others, we would expect the average usage for male Justices to increase during that Justice’s tenure on the Court. This wouldn’t fully explain the parallel peaks and valleys we see in both male and female Justices’ “women’s language,” but it might account for some of the more general trends. Likewise, the subject matter of cases might have an effect on “women’s language.” In years where case subject matters are more technical or less accessible to most of the Justices, we might see more hesitations and hedges.[160] Still, though, any of these explanations seem unlikely to explain male Justices’ increased rates of “women’s language” with the addition of each female Justice.

Whatever the cause of parallel rates of “women’s usage” for male and female Justices, we find the dynamic noteworthy. If it is the case that the presence of women on the bench can cause changes in the speech patterns of their male counterparts, it raises the possibility that the presence of women can affect other aspects of courtroom proceedings and decision-making. Our very brief discussion of possible explanations serves only to flag this issue for future study.

* * *

While we cannot speak conclusively as to the cause of any pattern we observe and describe above, our results show that women—whether advocates or Justices—consistently use “women’s language” more than their male counterparts. This finding alone, which lends credence to Lakoff’s initial hypothesis, has important implications that we more fully discuss in Part IV below. But we have also observed patterns in “women’s language” usage that raise additional questions not addressed by Lakoff’s hypothesis. We observe that men have increasingly used “women’s language” during oral arguments and that Justices use “women’s language” more than advocates of the same gender. We have also found that male and female Justices’ use of “women’s language” has historically risen and fallen in tandem. Below we explore some implications of these findings as well.

Implications

In the last fifty years, countless scholars have responded to, challenged, tested, and complicated Robin Lakoff’s hypothesis that female speakers use a distinct “women’s language.”[161] The foregoing analysis adds to that rich literature by using statistical lexical methods to analyze “women’s language” in Supreme Court oral arguments. As explained above, our analysis shows clear patterns of gendered language at the Supreme Court: Female speakers do, in fact, tend to use the tropes of “women’s language” more frequently than their male counterparts.[162] We also observe that men are increasingly using “women’s language,” and that Justices use “women’s language” more than advocates of the same gender. We also take note of the curious parallel historical trends in male and female Justices’ use of “women’s language.”

These results have important substantive and normative implications. In this Part, we first explain how our findings enhance and complicate prevailing understandings of “women’s language.” Specifically, we describe how our findings contribute to existing debates about the existence of “women’s language.” We also note how our findings complicate the hypothesis that “women’s language” is a function of power rather than of gender. Next, we consider the normative implications of our results. Specifically, we examine “women’s language” both as a symptom of inequality and as a deliberate rhetorical strategy. We then consider how the Supreme Court’s reinforcement of “women’s language” patterns might affect the legal profession, either by perpetuating subordination or by helping to destigmatize the speech style. Finally, we describe avenues for future research.

Substantive Implications

First, and most obviously, our results provide evidence that “women’s language” is, in fact, an observable phenomenon. This contribution is meaningful because, despite fifty years of research, many scholars do not agree that “women’s language” actually exists.[163] Because we are the first to analyze “women’s language” at the Supreme Court, our results provide new reason to believe that women and men speak differently, at least in the oral argument context. Our findings also stem from rich lexical methods, which are more powerful and precise than the manual techniques researchers have used in the past.[164] Though our analysis is, admittedly, quite simple, it reveals clear differences between male and female speech during Supreme Court oral arguments. These findings provide new and important evidence for Lakoff’s original hypothesis.

Our findings also complicate the competing theory—first articulated by William O’Barr and Bowman Atkins—that language varies with power, not with gender.[165] O’Barr and Atkins defined power as “social standing in the larger society and/or status accorded by the court.”[166] At the Supreme Court, nearly every speaker is “powerful” in the former sense: Justices and advocates are all “well-educated, professional,” and of relatively high “social status in the society at large.”[167] But there is a clear hierarchy in “status accorded by the court”: The nine Justices are arguably the most prestigious attorneys in the United States and hold all decision-making power; advocates, by contrast, are experts in their respective cases but have no control over questioning or outcomes. If O’Barr and Atkins’s hypothesis is correct, then, we might expect to see advocates (the less powerful players) using “women’s language” more often than Justices. But as discussed in Section III.C, above, that is not what we found. Instead, our analysis shows that Justices use Lakoff’s tropes at a higher rate than advocates, regardless of gender. These findings are difficult to square with O’Barr and Atkins’s proposition that power, rather than gender, predicts which speakers use Lakoff’s tropes.

Normative Implications

In addition to complicating the existing literature on language, gender, and power, our research raises important normative questions about what “women’s language” means for and about female attorneys and the law. In her original article, Lakoff argued that “women’s language” is both a symptom and source of gender inequities.[168] If this is true, what does “women’s language” at the Supreme Court signify? And what new inequities might it cause?

“Women’s Language” as a Symptom

Participants in Supreme Court oral argument are highly trained, highly educated, and well prepared. For any given case, advocates might spend hundreds of hours rehearsing and mooting their arguments.[169] Justices likewise come prepared with questions and follow-ups. Given how rehearsed and practiced arguments are, it is somewhat surprising that “women’s language”—with all its “ums,” “sorrys,” and stutters—appears at all. The fact that advocates use less “women’s language” during their highly prepared opening statements than during the remainder of oral argument suggests that they recognize (or, perhaps, have been taught) that “women’s language” is not the most effective or powerful way to convey ideas.[170] But if oral argument participants scrub “women’s language” from opening statements, why do they pick it up again during the rest of the argument?

One explanation might be that the women in our dataset do not select “women’s language” consciously at all. As Lakoff notes, little girls who “‘talk[] rough’ like a boy [are] normally . . . ostracized, scolded, or made fun of.”[171] Girls are thus socialized from a young age to use language that is soft, tentative, and hesitant. When they grow to womanhood, Lakoff argues, that socialization process ensures that many women are “unable to speak precisely or to express [themselves] forcefully.”[172] Perhaps that is true even at the Supreme Court: “Women’s language” might be so deeply engrained in societal norms that it naturally creeps into spontaneous speech, even if it can be edited or rehearsed out of opening statements.

The women in our dataset might also default to “women’s language” because they have long occupied a subordinate position in the legal profession.[173] Since its inception, the practice of law has been dominated by men.[174] And despite remarkable gains made in the last fifty years, women remain underrepresented on the bench, in federal clerkships, and in other prestigious legal positions.[175] Given these dramatic and longstanding gender disparities, it is perhaps unsurprising that women still present themselves using language patterns that some perceive as tentative, timid, and weak.

A final, and more optimistic, possibility is that the women in our dataset intentionally select “women’s language” for its communicative advantages. Curiously, Benjamin Franklin recounted doing just that. In his autobiography, he described deliberately using hedges, super polite forms, hesitations, and other tropes that we now associate with “women’s language.” Reflecting on the effects, he wrote, “[T]he conversations I engag’d in went on more pleasantly. The modest way in which I propos’d my opinions procur’d them a readier reception . . . I had less mortification when I was . . . wrong, and I more easily prevail’d with others . . . when I happened to be in the right.”[176] In recent years, some scholars have similarly proposed that “women’s language” can be “used to good effect.”[177] For instance, linguist Jennifer Coates suggests that hedges can help a speaker “respect the . . . needs of all [conversation] participants, . . . negotiate sensitive topics, and . . . encourage the participation of others.”[178] Linguist Janet Holmes urges that “women’s language” improves decision-making, problem-solving, and cooperation, especially in professional settings.[179] And Susan Schick Case, a professor of organizational behavior and gender studies, claims that in complex, multicultural organizations, “certain features of women’s speech . . . influence the performance and goal attainment of the organization as a whole, as well as help in the development of complex and novel decisions that require pulling together perspectives and information from many different groups.”[180]

If these observations are correct, then “women’s language” could be an asset in various professional settings. In the legal field, the ability to “encourage the participation of others” and artfully navigate “sensitive topics” is an essential skill—for negotiations, attorney-client relations, persuading judges and juries, and other purposes.[181] And in any profession, communication that facilitates decision-making, problem-solving, and cooperation is a boon.[182] If “women’s language” yields these advantages, it is possible that the women in our dataset—all sophisticated users of language—intentionally use “women’s language” to achieve their communicative objectives. The patterns we observe might thus be evidence of purposeful rhetorical decisions rather than proof of systemic gender inequality.[183]

“Women’s Language” as a Source

In addition to whatever “women’s language” might reflect about society, the legal profession, and the individual speakers in our dataset, its presence during Supreme Court oral argument has the potential to shape norms and expectations going forward. The Supreme Court is the most prominent judicial institution in the United States, if not the world. Its Justices are admired and revered. And its advocates are considered some of the best in their field. The Court’s proceedings and opinions are studied and emulated in moot court competitions, legal research and writing programs, and doctrinal classes. If young lawyers see participants in Supreme Court oral arguments using “women’s language,” they may consciously or subconsciously learn that “women’s language” is how good female attorneys speak. The result might be that young female lawyers emulate the “women’s language” they observe, while young male lawyers come to expect “women’s language” from their female colleagues.

Whether this is beneficial or problematic depends on how one assesses “women’s language” to begin with. If Lakoff is correct that “women’s language” “systematically deni[es] [women] access to power,”[184] there is reason to worry that the Supreme Court is modeling—and by extension perpetuating—norms of gender inequality and subordination. In the legal field, strong communication skills are vital to career advancement. Attorney speech is evaluated in interviews, at trial, in oral argument, and in interactions with coworkers. So, if “women’s language” is in fact a source and sign of weakness, women in the legal profession may be marked as less sophisticated because they use it. They might also face the added—and in many ways invisible—hurdle of scrubbing “women’s language” from their vernacular. Whether women choose to proceed using “women’s language” or not, they could face heightened scrutiny compared to their male counterparts as society polices and penalizes their communication style.

If, however, Coates, Case, and others are correct that “women’s language” has communicative benefits,[185] then perhaps we ought to rejoice that these rhetorical techniques are on display at the Supreme Court for Americans of all genders and professions. If “women’s language” is a valuable rhetorical tool, then there is good reason for the legal profession to welcome, celebrate, and elevate those who use it. And if male attorneys begin using more “women’s language” (as we see them doing at the Supreme Court), then the entire legal field might benefit from its relationship-facilitating, cooperation-inducing effects. Put differently, “women’s language” might be one of the many ways that female lawyers have “feminized” the legal profession for the better.[186]

Paths Forward

Like all studies, our analysis is limited. Though we analyzed an enormous amount of text, our corpus did not contain many instances of “women’s language,” because until recently, there were not many women on or at the Supreme Court. Thus, especially for the earlier years in our dataset, our findings are noisy. Additionally, we only analyzed four of Lakoff’s tropes, so we did not capture the full spectrum of what Lakoff considers “women’s language.” And we used Lakoff’s original framework without any of the modifications or revisions that subsequent scholars have added.[187] A sociolinguist might thus object that our framework is incomplete or outdated. They would probably be right.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our analysis is the first to study “women’s language” during Supreme Court oral arguments. And it provides clear evidence that “women’s language” exists in that context. Our study thus makes an important preliminary contribution to the study of gender, language, and law.

As the first of its kind, though, our analysis leaves many questions unanswered. We hope that future researchers will continue what we have begun by asking deeper and more nuanced questions about gender, language, and the law. For example, as researchers have done in other fields, legal scholars might analyze whether “women’s language” affects the way speakers are perceived or received—for example, whether female Justices who use “women’s language” are seen as less competent or capable than their male colleagues.[188] Legal scholars might likewise consider whether “women’s language” affects the substantive outcome of a case. Future researchers could also ask whether “women’s language” varies depending on the subject matter of the case—for example, if female speakers use less “women’s language” in cases that involve women’s issues. They might also analyze whether “women’s language” varies depending on the gender of the listener.[189]

Most importantly, though, future researchers should explore the normative implications of “women’s language” in the law. As we have noted, the “women’s language” we observe during Supreme Court oral arguments might be either positive or negative—an intentional, strategic rhetorical choice or a symptom of systemic inequality. Because our goal in this Article has simply been to identify “women’s language,” we have not taken a normative stance on whether the phenomenon is discouraging or hopeful. We hope future researchers will take up that task. Experiments and interviews could help determine whether “women’s language” in oral argument and other legal contexts has the positive, communication-facilitating effects that scholars like Coates, Case, and Holmes posited.[190] Ethnographic research might also help us understand whether speakers use “women’s language” intentionally (which would suggest that it is a deliberate and strategic choice) or habitually (which might indicate that “women’s language” is symptomatic of a deeper social problem). These and other efforts to understand the normative significance of “women’s language” will better equip legal scholars and practitioners to respond to and address its effects.

Conclusion

In business, healthcare, education, sociology, linguistics, and other fields, scholars have spent considerable energy researching how women use language to construct their social and professional identities.[191] In law, by contrast, we know very little about how women express themselves. This paper has begun to fill that gap by providing a first-of-its-kind study of female speech during Supreme Court oral arguments. Specifically, we used lexical methods to identify and analyze four tropes of “women’s language” in a corpus of more than six thousand oral arguments, and we found clear evidence that women participants in oral argument use each of those tropes more than their male counterparts.

These findings prompt important questions about women’s status in the legal profession. Since the early 1970s, scholars of gender and discourse have suggested that “women’s language” is both a symptom and source of gender inequality. Even so, other studies have argued that “women’s language” can be a valuable rhetorical tool that fosters cooperation and improves decision-making.[192] If it is true that “women’s language” signals inequality, then the prevalence of “women’s language” at the Supreme Court suggests that, notwithstanding their ever-increasing numbers, women in the law are not (or do not feel) equal. But regardless of which view is correct, scholars interested in gender, language, power, and equality ought to take seriously this possibility—especially at a time when issues of women’s legal rights are increasingly before the Court.

** Professorial authors are listed first in alphabetical order by last name, followed by professional authors in alphabetical order by last name. The authors would like to thank the many brilliant people who helped bring this project to fruition, including (but not limited to): Tom Lee, Annalee Hickman Pierson, the faculty at the Chase College of Law (Northern Kentucky University), the participants at the 2025 Law and Society annual meeting, and the excellent editors at the Colorado Law Review.

† J.D., Charles E. Jones Professor of Law, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University.

‡ J.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University.

** Ph.D., Associate Professor, Brigham Young University Department of Computational, Mathematical, and Physical Sciences.

†† J.D., J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University.

‡‡ J.D., J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University.

- Robin Lakoff, Language and Woman’s Place, 2 Language Soc’y 45, 48 (1973). ↑

- Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872). ↑

- Id. at 141 (Bradley, J., concurring). ↑

- Indeed, Bradwell might qualify as a part of the American anticanon. See Jamal Greene, The Anticanon, 125 Harv. L. Rev. 379, 464 (2011) (suggesting that “anticanon” cases are cases that are theorized incompletely and “inconsistent[] with [America’s national] ethos” but nonetheless reflect methods of legal reasoning that, at some level, seem correct). ↑

- Women in the Legal Profession, ABA (2024), https://www.americanbar.org/news/profile-legal-profession/women [https://perma.cc/V6S9-QG7R]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. Though this number is a significant improvement, it is obviously still not proportionate to the number of women in the general population or to the increasing number of women in the legal field. ↑

- Id. (“[M]en still dominate the upper echelons of the legal profession through federal judgeships, state supreme courts, law firm partnerships, and corporate counsel positions.”). ↑