“Sexting” is a term that refers to the exchange of sexually explicit or sexually suggestive messages or images between individuals using electronic messaging. Teenage sexting is a controversial legal topic because the act of taking nude or semi-nude pictures of a minor technically constitutes child pornography under federal law, even when those pictures were self-portraits taken by the minor in question. This Comment argues that the prosecution of sexting under federal child pornography law constitutes the criminalization of adolescent exploration of sexuality and that states should adopt their own sexting-specific laws to address teenage sexting in a manner that respects teenagers’ personal freedom and bodily autonomy. Part I of this Comment looks at the background of teen sexting, including the long history of teenage sexual expression. Part II examines the current state of the law across both federal and state levels. Part III observes the harm caused by the current law. Part IV describes potential solutions to the problems caused by the current law and proposes a new model law that is better tailored to the specific problems found in teen sexting.

Introduction

Jane Doe was a regular fourteen-year-old girl living in southern Minnesota—until she was caught “sexting.”[2] Jane had texted a revealing picture of herself to a boy she liked at school.[3] Without Jane’s knowledge or consent, that boy went on to distribute Jane’s revealing selfies to Jane’s classmates in school.[4] In January 2018, law enforcement officers found out about the revealing photographs,[5] and local prosecutors immediately charged Jane with felony distribution of child pornography, despite the fact that the revealing selfies were distributed against her will.[6] If Jane Doe is convicted, or even if she pleads guilty to a lesser charge, Jane Doe will be required to register as a sex offender for ten years simply because she took a photograph of her own body.[7]

While this situation might seem like an extreme outlier, cases like this one are all too common in the American criminal justice system. In a similar case, Iowa prosecutors threatened to charge a fourteen-year-old girl with sexual exploitation of a minor after she sent two pictures of herself in her underwear to another student.[8] Such cases are not limited only to girls: in North Carolina, a seventeen-year-old boy had his cell phone seized by police during an investigation.[9] When the police searched the phone, they found sexual pictures of the boy and his seventeen-year-old girlfriend.[10] Although two teenagers that age could legally have sex in North Carolina, it was (and still is) a crime for seventeen-year-olds to take sexual photographs of themselves.[11] North Carolina prosecutors immediately charged the boy with five counts of sexual exploitation of a minor. His name and crimes were published in the local newspaper and on television, and he faced the possibility of a lifetime as a registered sex offender.[12] In another shocking and grotesque case, a seventeen-year-old boy in Virginia was accused of texting a picture of his penis.[13] Police obtained a warrant to take the boy to a hospital and forcibly induced an erection to compare the boy’s penis to the one shown in the photograph.[14] Unfortunately, such criminalization of young people’s sexuality has become all too common—in 2018, the most common age for a registered sex offender was a mere fourteen years old.[15]

Despite the recent abundance of such prosecutions, teenagers engaging in this type of consensual sexual activity is not a new phenomenon. A study in 2008 sparked media outrage by revealing that one in five teenagers had sexted—that is, they sent or received sexually explicit text messages.[16] Teenagers soon became embroiled in legal battles when prosecutors throughout the country began to bring child pornography charges against teenagers who had sexted.[17] Because federal child pornography law makes no exceptions for self-produced images, teenagers can face felony charges, prison time, and even compulsory registration as sex offenders simply for taking a picture of their own bodies.[18]

This Comment argues that the prosecution of sexting under federal child pornography law constitutes the criminalization of adolescent exploration of sexuality and that states should adopt their own sexting-specific laws to address teenage sexting in a manner that respects teenagers’ personal freedom and bodily autonomy. Part I of this Comment looks at the background of teen sexting and the law, including the history of teenage sexual expression, the modern prevalence of sexting among teenagers, and the numerous causes of sexting. Part II examines current state and federal law. Part III explains the harm caused by the current law, including the violation of teenagers’ bodily autonomy, the unjustifiably harsh penalties imposed on teenagers, and the failure of the law to deter sexting. Part IV describes potential solutions to the problems caused by the current law and argues that both state and federal laws must be reformed to prevent future injustices. Ultimately, this paper concludes that sexting laws prosecute a victimless crime, impose punishment where there has been no wrongdoing, and inflict overly harsh punishments on teenagers in a misguided attempt to crack down on what amounts to no more than a natural function of teenage sexual development. In other words, the kids are alright, and the kids deserve better.

Background: Teen Sexting in Context

“Sexting” currently encompasses a wide range of behavior and refers to any messaging that utilizes internet or phone service, where either the messages or images contain sexual content.[19] For the purpose of this Comment, “sexting” will be used in a very specific context that aligns with the legal community’s general understanding of the concept. In relation to the law, “sexting” refers to “the practice of sending or posting sexually suggestive text messages and images, including nude or semi-nude photographs, via cellular telephones or over the Internet.”[20]

Before looking at the law as applied to modern teen sexting, it is essential to contextualize sexting in several distinct areas. These background elements, taken together, demonstrate that teenagers have always engaged in sexual experimentation for a plethora of biological and environmental reasons that are not unique to either cell phones or the modern era. The first section below recounts the history of sexualized messaging and teenage sexual expression, while also addressing whether modern sexting can be placed into historical context. The second section looks at the causes of teen sexting. These sections together clearly illustrate that teenage exploration of sexuality is neither new nor scandalous—rather, it is a consistent and natural part of teenage development.

History of Sexualized Messaging

Teenagers engaging in sexual activity is not a new phenomenon: stories centered around teen romance date back hundreds of years, and historical surveys indicate that teenagers have been consistently sexually active for at least the past half-century.[21] Perhaps surprisingly, modern American teenagers are currently having less sex than at any time since the 1970s.[22] A study conducted in 2014 indicated that teen pregnancy has decreased to a lower rate than at any time since the 1970s.[23] Yet, the impression given by the media has consistently been that teenagers are becoming more sexually provocative and more sexually active each year, despite the steady decline in teenage sexual activity over the years.[24]

Studies disagree as to the extent of modern teen sexting: the highest recorded frequency indicates that up to 71 percent of teenagers sext, while the lowest recorded frequency indicates that only 4 percent of teenagers sext.[25] Thus, the growing trend demonstrated by research is far from the “epidemic” cited by popular news outlets.[26] The media’s overblown and frantic response to teen sexting can be linked to the technological anxiety that characterized the early and mid-2000s,[27] the increased amount of news coverage available on television,[28] and the sensationalized agenda-setting common in televised news programming.[29] Some teenagers have responded to the media outcry to say that sexting is just “not that serious.”[30] Teen sexuality and sexualized communication are not new phenomena; far from being an “epidemic” of teenage sexuality run wild, sexting is simply the most recent iteration of teenagers’ timeless developmental desire to explore their own sexuality.

Even the act of sending sexualized messages and images is not a new phenomenon. History provides us a plethora of examples. One erotic portrait from the seventeenth century depicted a young woman with her breasts exposed, gently washing a string of sausages.[31] Voltaire famously wrote letters in the mid-1700s to a woman with whom he had a romantic relationship, in which he described his sexual organs and sexual acts.[32] Warren Harding wrote letters to his mistress in the early 1900s in which he described his genitals using the nickname “Jerry.”[33] James Joyce wrote similarly erotic letters to his wife in the early 1900s, in which he referred to his wife as “naughty,” used profanity, wrote erotic descriptions, and requested that his wife write him something of a similar nature in return.[34] Much like teen sexuality, sending sexualized images and messages is not a unique “sin” of our modern era but rather an old and common human activity that has only recently received heightened surveillance. The only “new” aspect of sexting is the technology through which sexualized messages and images are sent.

Causes of Modern Teen Sexting

To fully understand the phenomenon of teen sexting, it is essential to understand why teens engage in sexting behavior. Experts have identified two primary reasons why teens may choose to engage in sexting: first, teenagers explore their sexuality through common methods of communication; second, teenagers use sexting as a means of bonding with their romantic partners without becoming physically sexually active.

First, teenagers exploring their sexuality have easy access to new technology that enables them to explore their sexuality in the form of sexts.[35] Technology has become increasingly pervasive in society and more widely available to individuals of all ages. This is especially true among today’s adolescents with smartphones, whose access to the internet is substantially greater compared to previous generations.[36] Technology becomes widely available to adolescents during puberty, around the same time that physical changes in the brain and body cause young people to experience new and intense emotions—including sexual attraction.[37] Thus, sexting is primarily a result of readily available communications, imaging technology, and hormones.[38] Teens are using sexting, then, as a means of exploring their sexuality through technology because they are hormonally driven to do so and texting is such a common means of communication.[39] Moreover, sexting can be a healthy way for teenagers to explore romance, sexual attraction, and their own bodies in a safe way that does not require becoming physically sexually active.[40] This is why the vast majority of individuals who choose to sext report that the experience of sexting was an overwhelmingly positive one.[41] This is also why some adults choose to sext: adults sext even more frequently than teenagers, which casts doubt upon the argument that sexting only occurs among those too young to understand the potential risks.[42]

Second, teens often seek attention from a romantic partner or express their own romantic feelings through sexting.[43] Teenagers are more likely to sext if they are in a serious romantic relationship and are even more likely to sext if they are unable to see their partner in person, such as in long-distance relationships.[44] Indeed, some teens have described sexting as an activity for people who are in love as a way to express their romantic feelings.[45] Adolescent sexting behavior is significantly influenced by a teen’s romantic feelings for and relationship with the intended recipient of the sext.[46] Because sexting occurs as a natural[47] response to available technology and budding sexuality, many teens already flirt or hold romantic conversations over text—they may not even recognize when their own romantic texting has crossed the line into sexting.[48] For example, a teenager texting with someone they are romantically interested in might say, “What are you wearing?” “Oh, I’m just getting ready for bed.” “What do you wear when you sleep?” “Oh, I just sleep in my bra and underwear.” “Oh, really, I don’t believe you.” The teenager might take a photograph of themselves in their bra and underwear to “prove” this is how they sleep without realizing their flirtatious texts have crossed the line into sexting.[49]

Teenagers have always engaged in sexual exploration and expression. Despite the media frenzy surrounding the use of cell phones in teens’ sexual expression, sexting is not a radical expansion of the sexualization of teens.[50] Rather, sexting is the result of teens’ developmental desire to explore their sexuality, to gain attention from potential or existing romantic partners, and to make choices about their own bodies.[51]

The Current State of Sexting Laws

Due in part to the media’s response to teenage sexuality, state legislatures have begun to rapidly enact sexting-specific legislation.[52] The federal law that applies to sexting cases, however, has remained almost entirely unchanged. This Part addresses the state of current sexting law: the first section addresses federal law, while the second section addresses state law.

No federal laws specifically address sexting.[53] However, U.S. Attorneys looking to prosecute cases of teen sexting have relied heavily on another set of laws: those against child pornography. Teenagers caught sexting are typically prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. §§ 2251, 2252A(a)(2), and 2257A (together, referred to as the Prosecutorial Remedies and Other Tools to End the Exploitation of Children Today Act of 2003), which strengthened the enforcement and penalties against any obscene materials that depict children.[54] Under this law, the first offense of using a child to produce pornography holds a prison sentence of fifteen to thirty years.[55] If a teenager is caught sexting, the teenager can be charged under these laws;[56] the charge does not consider whether the teenager is the subject or recipient of the graphic image.[57]

Teenagers who are prosecuted for child pornography must also register with their state’s sex offender registry under the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, which was established in 1994 as a method of tracking sex offenders.[58] The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act, which was published in 2006, also created a federal sex offender registry with which teenagers prosecuted under child pornography laws may be required to register.[59]

Federal child pornography law criminalizes the action of photographing a minor in any sexualized way,[60] but federal law does not consider the age of consent in any given state nor does it consider whether the image was self-produced. Ultimately, this means that two individuals under the age of eighteen could legally have sex, but if they were found in possession of any sexually explicit photographs of each other, they could still be charged under federal child pornography laws.[61]

State Laws Regarding Teen Sexting

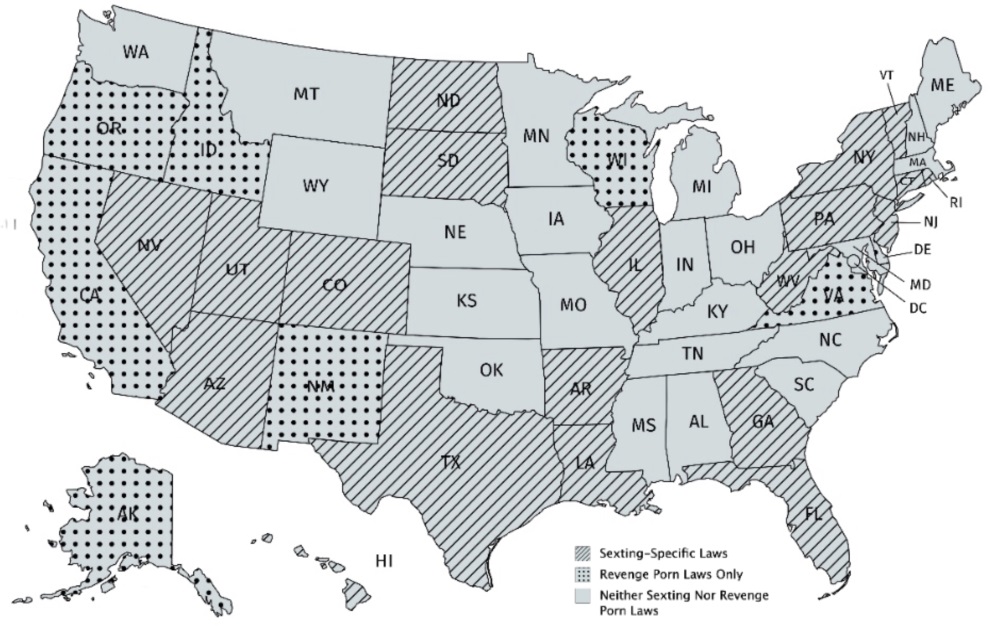

States take one of three primary approaches to sexting laws. Some states have one or more sexting-specific laws. Other states do not have sexting-specific laws, but they do have nonconsensual pornography laws that prohibit the distribution of intimate photos without a user’s consent. Still other states have neither type of law: in these states, there are no laws regarding sexting or the distribution of private intimate photos. The map above demonstrates which stance each state has taken on this issue: adoption of sexting-specific laws, adoption of nonconsensual pornography laws only, or lack of adoption of any law on this topic.

As of 2018, approximately twenty states have passed sexting-specific laws. These states include Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Vermont, and West Virginia.[62] Most of these reforms simply offer less severe sentencing options. In Rhode Island, for example, sexting is a status offense[63] that is tried in family court. Yet the law explicitly states that the juvenile may not be charged under state child pornography laws, will not be deemed a “sex offender,” and will not be required to register.[64] However, some states have introduced fairly complex regulatory schemes that differentiate between different “types” of sexting: Colorado’s sexting law, for example, creates three tiers of offenders.[65] Under the first tier, teens who are approximately the same age and who exchange sexual images with the understanding of consent have committed a civil infraction and may be required to participate in an educational program.[66] Under the second tier, teens who possess an image of another teen without their permission have committed a petty offense, with the potential to rise to a Class 2 misdemeanor if the possessor has images of between three and ten separate persons.[67] Under the third tier, teens who distribute or post images of either themselves (if the recipient did not request the photograph and it caused the recipient emotional distress), or other teens (who had a reasonable expectation that the images would remain private), have committed a Class 2 misdemeanor.[68] That charge can be enhanced to a Class 1 misdemeanor if: (1) the poster had an intent to coerce, intimidate, or cause emotional distress; (2) the poster had previously been found guilty of a sexting offense; or (3) the poster had posted images of three or more separate persons.[69]

While not all states explicitly forbid teen sexting, the sharing or distribution of sexts without the user’s consent may still be barred in states with nonconsensual pornography laws.[70] “Nonconsensual pornography” refers to the sharing of another person’s sexually explicit or intimate images without his or her permission.[71] The term “nonconsensual pornography” describes the sharing of images originally obtained with consent that are later shared without the subject’s consent (such as when an intimate photograph is consensually shared with a single person, but the image is later shared with third parties without the subject’s consent).[72] Nonconsensual pornography is different from sexting.[73] Sexting occurs when an individual takes a sexually explicit photograph and shares that photograph with another person with both the knowledge and intent that the recipient will view the sexually explicit image.[74] However, if the recipient of that sexually explicit image were to share or distribute that image without the subject’s consent (by showing the image to others in person, texting it to others, sharing it online, or any other means of distribution that lack the subject’s consent), such an act would be an act of nonconsensual pornography.[75] Many states without sexting laws still criminalize the act of distributing sexually explicit photographs without the subject’s consent through nonconsensual pornography laws.[76] Other states have no sexting laws and also do not have any nonconsensual pornography laws.[77]

In states with sexting-specific laws, prosecutors may decide whether to prosecute under federal or state law. This allows prosecutors more flexibility in pressing charges that fit the nature of the crime committed.[78] In states without sexting-specific laws, however, prosecutors dealing with teen sexting cases are left with a difficult question: whether to pursue child pornography charges or to drop the charges entirely. Even prosecutors who might wish to pursue lesser charges are bound by the lack of a sexting-specific law and forced to choose between pressing felony charges or dropping all charges. Faced with such a choice, many prosecutors choose to press charges against teens for producing child pornography—a felony that requires the teen to register as a sex offender if convicted.[79]

The Harm Caused by Current Law

This Part describes three primary harms caused by prosecuting teens under federal child pornography law for the act of consensual, private sexting. First, teenage bodily autonomy is violated when the government polices the bodies of consenting young people. Second, the overly harsh sentences levied against teens convicted of sexting are unjust because teenagers are marked for life for actions undertaken as adolescents. Finally, the current law fails to deter sexting in any way and may incentivize young people to commit further crimes.

The criminalization of sexting legislates how teenagers should use their bodies and unjustifiably strips teenagers of their own right to bodily autonomy and sexual privacy. Teenagers have a partially recognized constitutional right to self-determination over their own bodies and sexual activities, provided that they understand and can make intelligent decisions about their circumstances.[80] In Bellotti v. Baird, the Supreme Court held that “mature” minors have a constitutional right to access abortion services without parental consent and that “[t]he child’s right to constitutional protection is virtually coextensive with that of an adult.”[81] The Court found that “children generally are protected by the same constitutional guarantees against governmental deprivations as are adults,” but the government may adjust the legal system to account for the vulnerability of children and the child’s need for concern, sympathy, and parental attention.[82] The Court focused its analysis on how to best respect children’s constitutional rights. At the same time, the Court acknowledged that children are uniquely vulnerable and often need guidance from their parents as well as protection from the full force of the law.[83]

Further, in Planned Parenthood of Central Missouri v. Danforth, the Court held that “[c]onstitutional rights do not mature and come into being magically only when one attains the state-defined age of majority.”[84] The Court cited a dissenting opinion from the lower court, arguing that a woman under the age of eighteen seeking an abortion should be “entitled to the same right of self-determination now explicitly accorded to adult women, provided she is sufficiently mature to understand the procedure.”[85] The Supreme Court’s decision focused on the teenager’s maturity, understanding of the situation, and ability to make rational decisions regarding her own body.[86] While the Court accepted that not all children are equally capable of mature, rational decision-making, the Court found that a law that restricted the constitutional rights of juveniles without consideration for their potential maturity lacked sufficient justification for the restriction.[87] Some states formally codify the right of minors to engage in consensual sexual activities with other minors of a similar age in so-called “Romeo and Juliet” laws, which recognize that juveniles are capable of informed consent and rational decision-making regarding their own bodies.[88] Like other forms of sexual expression, sexting is best understood as an exercise of bodily autonomy and the teenager’s own private sexual choices.[89]

The criminalization of teen sexting, therefore, represents an attack on teenagers’ bodily autonomy, self-determination in their own private choices, and right to sexual privacy.[90] Laws that deprive teenagers of their right to control (and photograph) their own bodies are antiquated, are based on fear of teen sexuality, and serve only to suppress sexual autonomy and sexual development in consenting teenagers.[91] Rather than harshly penalizing teenagers for sexual activity, the law must instead acknowledge that teenagers have a constitutional right to bodily autonomy. Courts and lawmakers alike must assert, like the Court in Bellotti v. Baird, that the proper role of the state is to protect the constitutional rights of children and prevent overly harsh penalties from being imposed on children who are still developing and uniquely vulnerable.[92] Instead of criminalizing adolescent sexuality in the digital world, laws regarding sexting should focus on the minor’s ability to provide informed consent, his or her autonomous actions as an independent person, and his or her capability for rational decision-making.[93]

Overly Harsh and Unjust Sentences Levied Against Teens

Laws against sexting are facially unjust due to the disproportionate level of punishment meted out for a decision made as a teenager. Children who are convicted of charges relating to sexting are marked for life in real, discernable ways with permanent consequences, including being branded as a felon and forced to register as sex offenders while still in their teenage years. Children are too often required to register as sex offenders; in 2018, the most common age for a registered sex offender was fourteen years old.[94]

Teenagers who are convicted of sexting under child pornography laws are legally classified as sex offenders and are required to register as such.[95] While different states and statutes have different requirements, sex offenders may have to register for a period of time or for their entire life.[96] In the United States, the stigma of registering as a sex offender has the potential to linger long after removal from a formal database, due to the easily searchable nature of such registrations. Some states even have a “click to print” icon beside a sex offender’s pictures, so the mugshots can be easily printed and shared.[97] Most sex offenders report having been physically or verbally harassed or fired from their place of employment after their registration status was discovered.[98]

Unfortunately, the registration requirement and attendant social stigma are often the mildest of the consequences. Sex offenders are sometimes barred from areas where children congregate.[99] Georgia, for example, legally prohibits registered sex offenders from living or working within one thousand feet of a school, church, park, skating rink, or swimming pool.[100] Some sex offenders are entirely unable to find homes due to these restrictions and have become permanently homeless.[101] In some cases, sex offenders have even been murdered based on their registration status.[102]

This social stigma is especially concerning because the public is often unaware that sex offender registries do not distinguish between serious offenses and petty offenses. Based upon the sex offender registry alone, it is impossible to know whether the name is listed due to a violent sexual assault or the simple act of sexting during adolescence.[103] These laws are especially punitive for an individual who was required to register at a young age: such individual may have committed a regrettable error as a teen but will be marked for life as a sex offender. The lasting collateral consequences of sex-offender status for teenage sexting could include being barred from taking one’s own children to a playground or swimming pool later in life.[104] These individuals will be forced to live their entire adult lives as registered sex offenders.[105]

The Supreme Court has previously recognized that lifelong punishments may be unjust when imposed on juveniles. In Roper v. Simmons, the Court recognized the injustice of imposing a lifetime prison sentence on a juvenile for three primary reasons.[106] First, juveniles have an underdeveloped sense of responsibility, which encourages them to engage in more risky behavior.[107] Second, compared with adults, juveniles are “more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure.”[108] Finally, juveniles’ personalities and characteristics are “not as well formed” as those of adults, and juveniles may be more likely to experience personal growth or change.[109]

The Supreme Court again recognized that children are constitutionally different from adults for sentencing purposes in both Graham v. Florida[110] and Miller v. Alabama.[111] In Miller, the Court recognized that justice requires that punishment for a crime be proportional. Accordingly, because of the characteristics of youth and the long lives that juvenile offenders have left to live, lifelong sentences imposed on juveniles are often disproportionate.[112] At least one court has already recognized that the logic applied to prohibit lifetime prison sentences for juveniles should also be applied to prohibit lifetime sex offender registry requirements for juveniles. Citing Roper, Graham, and Miller, the Colorado Court of Appeals held in In re T.B. “that requiring a juvenile, even one who has been twice adjudicated for offenses involving unlawful sexual behavior, to register as a sex offender for life without regard for whether the teenager poses a risk to public safety is an overly inclusive—and therefore excessive—means of protecting public safety.”[113] Lawmakers must recognize that imposing lifelong sex offender status on juveniles, which permanently threatens the juvenile’s safety and livelihood, is fundamentally unjust.

Failure to Deter

The overly harsh legislation currently used to prosecute teen sexters does not effectively deter teenagers from sexting.[114] Surveys indicate that teenagers are generally unaware of the legal risk and repercussions associated with sexting.[115] Other studies have shown that “fear-based” approaches to deter risk-taking behavior by teens—such as increased criminal penalties and an increased threat of prosecution—simply do not work on teenagers.[116] Fear-based approaches fail to deter young people from engaging in risky behavior because they create the impression that the behavior in question is taboo and therefore exciting.[117] Another reason why harsh penalties are generally unsuccessful is that teenagers do not think about the law when they sext.[118] Studies show that teenagers find it difficult to make rational decisions in situations that involve new experiences or rapid decision-making, both of which are often present in teen sexting.[119] Additionally, teenagers are not well informed about the law. After being formally charged with a felony under a child pornography law for sharing sexts, one fourteen-year-old simply stated, “I didn’t know it was against the law.”[120]

Not only do overly strict sexting laws fail to deter teens from sexting in the first place, but teenagers who face the full force of the law are more likely to commit other sex-related crimes in the future.[121] Individuals who are forced to register may feel that they have already been marked for life and stigmatized by society. These individuals may accordingly believe they have little to lose by committing additional sex-related crimes. Thus, they may be more likely to recommit sex-related crimes compared to those who are not charged with a sex offense.[122] Rather than providing a deterrent effect, the application of overly harsh sexting laws to teens may only encourage these individuals to commit sex-related crimes in the future.[123]

Arguments Justifying the Current Law and Why They Fail

The current method of prosecuting teenagers caught sexting under federal child pornography law improperly strips teenagers of their partially recognized legal right to sexual privacy and imposes overly harsh criminal penalties on young people—yet it still fails to deter sexting. Even so, lawmakers still justify the criminalization of sexting under three primary theories: (1) sexting represents self-exploitation by teenagers; (2) sexting laws are necessary to protect young women from predatory teenage boys; and (3) sexting is a permanent act of wrongdoing and should therefore be punished to the full extent of the law. This section addresses each argument in turn and explains why these arguments ultimately fail to justify the criminalization of sexting.

First, some scholars have argued that sexting should not be understood as an expression of bodily autonomy but rather as an example of self-exploitation.[124] Professor Lara Karaian argues that the modern world is so inherently sexualized that teenagers may feel pressured by television and movies to act in sexualized ways. Thus, teen sexting represents a teenager’s surrender to societal expectations and sexualized self-exploitation in exchange for social acceptance.[125]

However, this argument simply does not square with the research, which indicates that a teenager’s decision to sext is primarily influenced by whether they are in a romantic relationship—not by their peer group or what societal pressures they experience.[126] Additionally, the argument that teen sexuality originates from societal pressure ignores the history of teen sexuality even in societies that were not overtly sexual. It also overlooks the fact that teen sexuality stems from developments that occur during puberty rather than the movies a teenager has seen.[127] Further, the argument that “self-sexualization” is inherently bad relies on the notion that teenagers are ideally chaste and should not explore their sexuality until after reaching adulthood—notions which run contrary to the history of, and science behind, teen sexual development.[128] Experts have shown that it is counterproductive to blame sexting on societal pressures or self-sexualization because, when framed in such a way, such discourse can erase young people’s capacity for choice and exploration of sexuality.[129] Finally, because sexting laws fail to deter the act of sexting, arguments regarding preventing teens from sexting are moot.[130] Far from “self-exploitation,” teen exploration of sexuality can be a way for teenagers to become comfortable with their changing bodies and hormones, easing the transition from childhood to adulthood.[131]

The second primary argument offered by authors who focus on criminal justice is that even if sexting primarily stems from teenagers’ healthy desires to explore sexuality, sexting should remain criminalized in order to protect young women from being pressured by young men into sexting against their will.[132] Indeed, many discussions around sexting criminalization focus disproportionately on young women as “at risk” for being pressured into sexting beyond the extent to which they would normally consent, and those who discuss the benefits of sexting criminalization often purport that it protects young girls.[133] However, this argument is similarly unsupported by the evidence.[134] The evidence suggests that young women—far from being powerless victims of male sexuality—are equal and active participants in sexting and sext at similar rates and in similar manner compared with young men.[135] In fact, the criminalization of sexting may in fact cause greater harm to young women by publicizing young women’s sexting and encouraging the “slut shaming” of women who choose to sext.[136]

The third argument offered, particularly by concerned parents and teachers such as Dr. Beth Robinson, is that teen sexting should be criminalized to avoid the nonconsensual distribution of a teenager’s intimate photographs.[137] However, sexting does not inherently involve the spread or distribution of the sexted images, and the law can address the two issues separately. States can and should provide a remedy for individuals who have their intimate photographs distributed without their consent. Such remedies can be provided through separate nonconsensual pornography statutes, which specifically address the nonconsensual sharing of intimate photographs among people of all ages.[138] These nonconsensual pornography laws criminalize the act of sharing intimate photographs without the subject’s consent without criminalizing the consensual sexting of intimate photographs.[139] It is unnecessary to criminalize the act of consensual sexting among minors to provide a remedy for victims of revenge porn.

Child pornography laws were instituted with the purpose of protecting children from being sexually victimized, but when the images in question are consensually produced by the child him or herself, child victimization is not an issue.[140] When law enforcement officers prosecute sexting cases, doing so only serves to bring further attention, stigmatization, and legal pressure to young teens whose only crime was to photograph their own bodies.

Potential Solutions: Striking a Balance Between the Protection and Indiscriminate Prosecution of Teens

Given the many problems associated with the prosecution of sexting under federal child pornography laws, the law clearly must be revised to protect teenagers from suffering overly harsh punishment. Additionally, states must enact their own sexting-specific laws to formally decriminalize consensual sexting among teens but should separately punish the nonconsensual distribution of intimate photographs. This part addresses possible solutions for the sexting problem while offering some suggestions as to how new state-level laws should be written to avoid the current problems associated with prosecuting sexting under federal child pornography laws. The first section argues that Congress should revise federal child pornography laws to exclude self-produced images and that Congress should further take action to amend the sex offender registry requirements in a manner that will protect teens. The second section argues that consensual sexting between minors should be decriminalized and that nonconsensual sexting should be addressed in a manner appropriate for juveniles.

Congress should amend federal child pornography laws in a manner that treats self-produced child pornography separately from child pornography produced by another person. Some potential reforms include making self-produced child pornography a misdemeanor, making it a summary offense, making it a status offense, punishing self-produced child pornography differently depending on the number of offenses, and classifying minors as a protected class from child pornography charges.[141] But perhaps the best reform would be to add amendments exempting self-produced child pornography from federal child pornography laws entirely if the case meets a very narrow definition of “self-produced.”[142] Such a definition should be drafted using a list of factors for consideration to allow courts to holistically assess each case based on the specific circumstances present. The factors listed in the definition should include the subject’s capacity for understanding the situation, the subject’s informed consent over the use and distribution of the photograph in question, and whether the image in question was primarily the result of the subject’s own choices or of coercion by the recipient. This would allow courts to determine whether the image was the result of child exploitation or of consensual, private sexting, and it would exclude the latter category from prosecution.

Congress should further amend the Sex Offender Registry and Notification Act to require that, as a separate step in the sentencing process, a jury approve all sex offender registry sentences.[143] The Act requires that sex offender registration be applied to a case by an “appropriate official” but does not specify how such sentencing ought to occur.[144] Currently, the sex offender registry requirement is imposed by the judge at the conclusion of the case and is determined by looking at the ultimate charges that were sustained rather than the underlying conduct.[145] The introduction of a jury into this process would solve many problems by allowing a group of individuals to determine whether the convicted person is truly a threat to society. While judges tend to look at the general criminal law that a person has been convicted of, a jury would instead look to the underlying conduct to determine whether sex offender registration is appropriate. Additionally, being sentenced by a jury of peers would allow a person convicted of sexting to be judged by other individuals in the same situation, who may be more familiar with sexting than would a single judge, and who may be hesitant to apply the same harsh registration requirements on young teenagers.[146]

States Should Revise or Enact Sexting-Specific Laws to Address Consensual Sexting Between Minors

While the federal law is being redrafted, states should enact state-level, sexting-specific laws to prevent prosecution of sexting under federal child pornography laws. The state laws should remove the option for prosecutors to bring charges against teenagers who privately and consensually sext, but the laws should provide prosecutors with an option for bringing charges against those who distribute intimate photographs without the subject’s consent.

States should enact legislation that decriminalizes the act of consensual sexting between two minors. Such laws should ideally include definitions of both “sexting” and “consent” that are unique to minors in sexting cases[147] to address the issue that minors cannot legally “consent” and to avoid prosecution under the principles of statutory rape.[148] Such laws should also include a provision similar to the “Romeo and Juliet” laws, which consider the ages of the two individuals engaging in the sexualized conduct.[149] Finally, such laws should consider the age of consent in each given state and should contain no penalties for private sexting between individuals over the age of consent.[150] These state-level reforms, in addition to the necessary federal reforms, would completely remove the option for prosecutors to bring charges against teenagers involved in innocent sexting.

States should, however, criminalize the act of distributing intimate photographs without the subject’s consent to protect the privacy of individuals who choose to take intimate photographs.[151] States could accomplish this through implementation and enforcement of nonconsensual pornography laws, which would criminalize the nonconsensual sharing of intimate photographs without criminalizing the act of private, consensual sexting. Alternatively, states could create a new category of crime dubbed “aggravated sexting” to decriminalize sexting between two minors that is consensual while still criminalizing the nonconsensual distribution of sexts.[152] If a teen forwards, shares, or distributes an image without the sender’s consent, states could charge the teen with “aggravated sexting.” Such a charge could be punishable with community service, school suspension, juvenile detention, or other sentences that would serve to punish the teenager in a manner that would not cause permanent harm to the teenager’s life.[153] The best solution may involve a combination of both nonconsensual pornography laws and “aggravated sexting” laws. This would allow prosecutors some flexibility to charge the most serious of juvenile offenders under nonconsensual pornography laws.[154]

Urged on by media frenzy and unjustified panic regarding teen sexuality, overly zealous prosecutors have harshly penalized sexting—a generally victimless crime that takes place privately and consensually. As a result, teens have been marked for life by harsh and inflexible laws that serve only to criminalize teen sexuality. By changing the law, future injustices against teenagers will be prevented, and teen privacy and bodily autonomy may be protected in future sexting cases.

Conclusion

Teen sexting is unique to our time in history, but its roots are not—teens have always expressed their sexuality with other teens due to the physical developments in their brains and bodies, their newfound desire to act on romantic feelings, and pressures from peers and society alike. But while these behaviors are more normal than the media typically portrays, these behaviors can be dangerous if the messages or images become widely shared. In states that do not have sexting-specific laws, prosecutorial reliance on federal child pornography statutes results in a heavy-handed and ill-suited system that ruthlessly punishes teens in a manner that marks them for the rest of their lives. The current system represents a fundamental injustice against teens, which only serves to overload sex offender registries and potentially disserve true victims of child pornography. While many potential solutions and new laws have been discussed, the best law would be one which only targets the nonconsensual sharing of sexts rather than the production or viewing of consensually shared sexts, and which takes the age of the participants into consideration. The heavy-handed prosecution of children under federal child pornography law is an unjust and overly harsh response to a normal expression of teen sexuality. The kids are alright, and the kids deserve better.

- J.D. Candidate, 2020, University of Colorado Law School; Associate Editor, University of Colorado Law Review. I would like to thank the University of Colorado Law Review and all its members for their tireless work in preparing this article for publication. In particular, I would like to thank Perdeep Badhesha, Andrew Jacobo, and Marty Whalen Brown for dedicating their time and effort to help complete this project. I would also like to thank my mother, Brenda Bayliss, for her advice and support throughout the drafting process. Finally, I would like to thank my husband, Joseph Samelson, without whom this article would not have been possible. ↑

- . Teresa Nelson, Minnesota Prosecutor Charges Sexting Teenage Girl with Child Pornography, ACLU: Speak Freely (Jan. 5, 2018, 11:45 PM), https:// www.aclu.org/blog/juvenile-justice/minnesota-prosecutor-charges-sexting-teenage-girl-child-pornography [https://perma.cc/CXM5-QPBQ]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Bridgette Dunlap, Why Prosecuting a Teen Girl for Sexting Is Absurd, Rolling Stone (Oct. 7, 2016, 6:35 PM), https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/ culture-news/why-prosecuting-a-teen-girl-for-sexting-is-absurd-127458/ [https:// perma.cc/4QEK-GSKT] (highlighting that in the first picture, the girl was wearing both underwear and a sports bra, while in the second picture, the girl was wearing only underwear, but her breasts were covered by her hair). ↑

- . Conor Friedersdorf, The Moral Panic Over Sexting, Atlantic (Sept. 2, 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/09/for-sexting-teens-the- authorities-are-the-biggest-threat/403318/ [https://perma.cc/4MLP-KHD7] (explaining that the investigation in this case originally dealt with an unrelated, non-sexting crime). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Friedersdorf, supra note 8. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Lenore Skenazy, There Are Too Many Kids on the Sex Offender Registry, Reason (May 2018), https://reason.com/archives/2018/04/09/there-are-too-many-kids-on-the [https://perma.cc/E7B7-9SF9]. ↑

- . The Nat’l Campaign to Prevent Teen & Unplanned Pregnancy, Sex and Tech: Results from a Survey of Teens and Young Adults 1 (2008), https://powertodecide.org/sites/default/files/resources/primary-download/sex-and-tech.pdf [https://perma.cc/7P3A-4W5C]; Eli Rosenberg, In Weiner’s Wake, a Brief History of the Word ‘Sexting’, Atlantic (June 9, 2011), https://www .theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/06/brief-history-sexting/351598/ [https:// perma.cc/W5NB-K3XG]. ↑

- . Dunlap, supra note 7 (“When the sexting panic hit in the late 2000s, prosecutors started charging kids with child pornography for photographing and filming themselves in consensual acts.”). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Sam Biddle, Where Did the Word “Sexting” Come From?, Gizmodo (June 10, 2011, 1:40 PM), https://gizmodo.com/5810722/where-did-the-word-sexting-come-from [https://perma.cc/YCD6-KASD]; see also Sexting, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sexting (last visited Aug. 8, 2019) [https://perma.cc/M53N-MU59] (defining “sexting” as “the sending of sexually explicit messages or images by cell phone”). ↑

- . Miller v. Mitchell, 598 F.3d 139, 143 (3d Cir. 2010) (adopting the plaintiff’s definition of “sexting” as “the practice of sending or posting sexually suggestive text messages and images, including nude or semi-nude photographs, via cellular telephones or over the Internet”). ↑

- . See, e.g., Steve James, Romeo and Juliet Were Sex Offenders: An Analysis of the Age of Consent and a Call for Reform, 78 UMKC L. Rev. 241, 242–43 (2009) (noting that some teenage romantic interactions are “not all that different” from the teen romance in Shakespeare’s famous play). Studies regarding historical levels of teen sexuality indicate that teenagers have consistently been sexually active, and sexual relations among teenagers is no new phenomenon. Phillips Cutright, The Teenage Sexual Revolution and the Myth of an Abstinent Past, 4 Fam. Plan. Persp. 24, 31 (1972) (“Hopefully, now that we have acknowledged that teenagers are having sex relations, recognizing it is no new thing, we may act sensibly and realistically to solve the problems consequent upon it, rather than cling stubbornly to the myth of an age d’or of sexual abstinence, or cheer on a largely non-existent ‘sexual revolution’ to topple the establishment.”); see also Melissa S. Kearney & Phillip B. Levine, Brookings Inst., Teen Births Are Falling: What’s Going On? 1 (2014); Gladys Martinez, Casey E. Copen & Joyce C. Abma, U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Servs., Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth, 23 Vital & Health Stat. Series, Oct. 2011, at 1, 5; Sandra L. Hofferth, Joan R. Kahn & Wendy Baldwin, Premarital Sexual Activity Among U.S. Teenage Women over the Past Three Decades, 19 Fam. Plan. Persp. 46, 50 (1987); Brent C. Miller & Kristin A. Moore, Adolescent Sexual Behavior, Pregnancy, and Parenting: Research Through the 1980s, 52 J. Marriage & Fam. 1025, 1025 (1990); Freya L. Sonenstein, Joseph H. Pleck & Leighton C. Ku, Sexual Activity, Condom Use and AIDS Awareness Among Adolescent Males, 21 Fam. Plan. Persp. 152, 154 (1989). ↑

- . Kate Julian, Why Are Young People Having So Little Sex?, Atlantic (Dec. 1, 2010), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/12/the-sex-recession/ 573949/ [https://perma.cc/HKB9-JCDB]. When teenagers do engage in sexual behavior, they do so in a far safer manner, making them less likely to experience sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancies compared to previous generations. Kearney & Levine, supra note 20, at 1. ↑

- . Kearney & Levine, supra note 20, at 1 (referring to the recent drop in teen pregnancy rates as a “stunning decline”). A 2018 report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that nationwide, only 39.5 percent of high school students had ever had sexual intercourse. Laura Kann et al., U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017, 67 MMWR Surveillance Summaries 1, 1 (2018). Most of these numbers come from older teens: only 13 percent of teenagers under the age of fifteen have had sex. Kathryn Stamoulis, Yes Your Teenager Is Having Sex . . . But It’s Not That Bad, Psychol. Today (June 14, 2010), https://www .psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-new-teen-age/201006/yes-your-teenager-is-having-sex-it-s-not-bad [https://perma.cc/M8NF-JWKZ]. ↑

- . For example, in 2005 the San Francisco Chronicle reported that teens were engaging in “rainbow parties,” which involved orgies of oral sex and multi-colored lipstick. Jeff Stryker, Over the Rainbow / Oral Sex Among Teens Is New Spin the Bottle, SFGate (Oct. 23, 2005, 4:00 AM), https://www.sfgate.com/ opinion/article/Over-the-rainbow-Oral-sex-among-teens-is-new-2563722.php [https://perma.cc/65ZY-JY2N]. In fact, no “rainbow parties” were ever documented outside of vague rumors. Cathy Young, The Great Fellatio Scare, Reason (May 2006), https://reason.com/archives/2006/05/05/the-great-fellatio-scare [https:// perma.cc/X6S5-W94P]. A similar scare took place in 2003, when reports speculated that the colorful bracelets worn by teens might correlate to sexual acts that the teenager had engaged in, with the color of the bracelets revealing the teen’s sexual history. Lauren Johnston, Fun Fashion, or Sex Signal?, CBS News (Dec. 10, 2003, 4:31 PM), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fun-fashion-or-sex-signal/ [https://perma.cc/68ZJ-9WG6]. The hype over these “sex bracelets” caused several schools to ban the colorful accessories, despite the lack of any real-world instances of teens using the bracelets to indicate sexual experience. Some argue the rumors of “sex bracelets” can be traced back to the 1970s, when parents were worried that their children were distributing “sex coupons” or “shag bands”—rumors that were similarly unsubstantiated. David Mikkelson, Sex Bracelets, Snopes (Mar. 31, 2014), https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/sex-bracelets/ [https:// perma.cc/KU5P-FKUE]. See generally Joel Best & Kathleen A. Bogle, Kids Gone Wild: From Rainbow Parties to Sexting, Understanding the Hype Over Teen Sex (2014) (describing how media has consistently overstated and exaggerated stories regarding teens’ sex lives, including inventing scandals regarding “sex bracelets,” “pregnancy pacts,” “rainbow parties,” and sexting despite a dearth of factual evidence). ↑

- . The most widely discussed study on teen sexting came from a survey conducted by The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy in 2010, which found that one in five teens reported that they had sent nude or seminude pictures of themselves to fellow teens. Nancy E. Willard, Sexting & Youth: Achieving a Rational Response, 6 Ctr. Soc. Sci. 4 (2010). Additionally, 71 percent of females and 67 percent of males reported sending sexually suggestive text messages to their significant other. Id. The Pew Research Center conducted a similar study in 2009, which found that only 4 percent of teens claim to have sent sexts, while 15 percent of teens claim to have received sexts. Amanda Lenhart, Pew Research Ctr., Teens and Sexting 2 (2009), http://www.pewinternet.org/ ~/media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Teens_and_Sexting.pdf [https://perma.cc/2ES6-VX3C]. The study showed that the age of teens correlated to their proclivity towards sexting: teens age seventeen or older were twice as likely to have both sent and received texts. Id. In 2009, a study from the Associated Press and MTV found that between 33 percent and 40 percent of teens had sexted. Heidi Strohmaier, Megan Murphy & David DeMatteo, Youth Sexting: Prevalence Rates, Driving Motivations, and the Deterrent Effect of Legal Consequences, 11 Sexuality Res. & Soc. Pol’y 245, 246 (2014). Another study conducted in 2014 found that 28 percent of respondents admitted to having sent sexts as teenagers. Id. Yet another study found that approximately 14 percent of teens had sent sexts, while 27 percent of teens had received sexts. Bruce Y. Lee, Here Is How Much Sexting Among Teens Has Increased, Forbes (Sep. 8, 2018, 10:22 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2018/09/08/here-is-how-much-sexting-among-teens-has-increased/#7f8cb4c636f1 [https://perma.cc/DV98-U74H]. ↑

- . See Marcos Ortiz, Why Is Teen Sexting Being Called an Epidemic?, ABC4 (May 10, 2017), https://www.abc4.com/news/local-news/why-is-teen-sexting-being-called-an-epidemic/711292231 [https://perma.cc/7W5Y-AXTF]. ↑

- . Kimberlianne Podlas, The “Legal Epidemiology” of the Teen Sexting Epidemic: How the Media Influenced Legislative Outbreak, 12 Pitt. J. Tech. L. & Pol’y 1, 6–9 (2011) (describing “technological anxiety” and its impact on adult perceptions of teen sexting). ↑

- . Id. at 21 (providing historical examples to demonstrate that increased media coverage of a topic correlates with increased public concern regarding that same topic). ↑

- . Id. at 9–18 (explaining that media reports on sexting spiked in 2009 following a string of sexting-related prosecutions, which further spread the media frenzy over sexting). ↑

- . Ahmina James, Criminalizing ‘Sexting’ Sends Wrong Message, S.F. Chron. (Mar. 22, 2009, 4:00 AM), https://www.sfgate.com/opinion/article/ Criminalizing-sexting-sends-wrong-message-3247606.php [https://perma.cc/MYH6 -KXR6]. ↑

- . Diane Kelly, “Sexting” Is Just a New Name for a Very Old Activity, Gizmodo (Aug. 28, 2015, 12:10 PM), https://gizmodo.com/sexting-is-just-a-new-name-for-a-very-old-activity-1726949863 [https://perma.cc/PGL2-C7EX]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Willard, supra note 24, at 1. ↑

- . Mary Madden et al., Pew Research Ctr., Teens and Technology 2013 1 (2013), http://boletines.prisadigital.com/PIP_TeensandTechnology2013.pdf [https://perma.cc/G8MG-NCCE]. In 2009, the Pew Research Center reported that 58 percent of teenagers owned a cell phone by the age of twelve. Lenhart, supra note 24, at 2. As of 2013, 93 percent of teenagers had access to the internet through a computer, and 78 percent of teenagers had a cell phone, nearly half of which were smartphones. See Madden et al., supra, at 2. The popularity and availability of cell phones among teens has only increased—in 2018, 95 percent of teens had access to a smart phone and 45 percent of teens reported being online “almost constantly.” Monica Anderson & JingJing Jiang, Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018, Pew Res. Ctr. (May 31, 2018), http://www.pewinternet.org/ 2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ [https://perma.cc/94YG-73LS]. ↑

- . Puberty is the time when the limbic system begins to mature at a faster rate than the frontal lobe. Puberty is thus accompanied by a “proliferation of receptors for oxytocin,” which causes teens to want to engage in more risky behavior to experience pleasure. Laurence Steinberg, A Social Neuroscience Perspective on Adolescent Risk-Taking, 28 Developmental Rev. 78, 89 (2008). The rapid limbic system development means that teens develop a strong “socio-emotional network” and are therefore more susceptible to certain strong emotions. Id. at 89–90. At the same time, less rapid frontal lobe and prefrontal cortex development means that teens have less impulse control compared with adults. Id. at 94–95. Adolescent brains are also less able to evaluate the risks involved in activities and may have more difficulty analyzing the potential long-term consequences of risky actions. Id. at 96, 99. ↑

- . Willard, supra note 24, at 1. ↑

- . Nicola Döring, Consensual Sexting Among Adolescents: Risk Prevention Through Abstinence Education or Safer Sexting?, 8 Cyberpsychology: J. Psychosocial Res. on Cyberspace 1 (2014). ↑

- . Tara Haelle, That Teen Sexting Study: What Else You Need to Know Before Freaking Out, Forbes (Feb. 27, 2018, 1:40 PM), https://www.forbes.com/ sites/tarahaelle/2018/02/27/that-teen-sexting-study-what-else-you-need-to-know-before-freaking-out/#3cf515e66569 [https://perma.cc/MW4W-GGPB]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . One survey from 2015 found that 88 percent of adults had previously sexted, and 82 percent of adults had sexted within the previous year. Diane Kelly, Psychologists Say that Sexting Can Be Good for You, Gizmodo (Aug. 10, 2015, 11:35 AM), https://gizmodo.com/grownups-sext-too-1722943639 [https://perma.cc/ K5SB-BXNY]. This figure is eleven percentage points higher than even the highest suggested rate of teen sexting, which is 71 percent. Willard, supra note 24, at 4. ↑

- . Willard, supra note 24, at 4. ↑

- . Michel Walrave, Wannes Heirman & Lara Hallam, Under Pressure to Sext? Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Adolescent Sexting, 33:1 Behav. & Info. Tech. 86, 86 (2013). ↑

- . What They’re Saying About Sexting, NY Times (Mar. 26, 2011), https:// www.nytimes.com/2011/03/27/us/27sextingqanda.html [https://perma.cc/P2KM-5UZS]. ↑

- . Willard, supra note 24, at 4. ↑

- . Those who are unconvinced that sexting is acceptable simply because it is natural should consider that sexting may even be safer than other forms of sexual expression: when done with the consent of both participants, sexting can be a safe way for teenagers to explore their sexuality without the pressure of an in-person meeting. In contrast to an in-person meeting, sexting participants feel free to withdraw or slow down at any time and can freely engage in some sexual activities without becoming physically sexually active. Nona Willis Aronowitz, When Is It Safe to Send a Partner Nude Photos?, Teen Vogue (May 2, 2019), https://www.teenvogue.com/story/when-is-it-safe-to-send-nude-photos-dtfo [https:// perma.cc/NJK6-46XY]. ↑

- . Nick Keppler, Adults Are Missing a Few Key Things About Teen Sexting, Vice (Aug. 8, 2017, 11:00 AM), https://tonic.vice.com/en_us/article/mgmemb/ adults-are-missing-a-few-key-things-about-teen-sexting [https://perma.cc/C3UY-JMM4] (explaining that teens who are romantically interested may send somewhat revealing photographs as part of otherwise normal conversation, which can blur the lines between flirting and sexting). ↑

- . Id. Numerous other factors may partially influence a teen’s decision to sext (such as the teenager’s sexual maturity, curiosity regarding sex, whether the teenager is in a romantic relationship, whether the teenager’s peers are sexting, and whether the teen has concerns about becoming physically sexually active but does not have the same concerns about sexting), but ultimately sexting represents a decision that a teenager makes regarding what to do with their own body. Raychelle Cassada Lohmann, 5 Reasons Teens Sext, U.S. News (May 18, 2017, 9:47 AM), https://health.usnews.com/wellness/for-parents/articles/2017-05-18/5-reasons-teens-sext [https://perma.cc/97X8-5R8N]. ↑

- . See supra Section I.A. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See, e.g., Thomas Crofts, Murray Lee, Alyce McGovern & Sanja Milivojevic, Sexting and Young People 25–42 (2015) (explaining how media is partially responsible for the actions of state and local governments regarding sexting). ↑

- . Kimberly O’Connor, Michelle Drouin, Nicholas Yergens & Genni Newsham, Sexting Legislation in the United States and Abroad: A Call for Uniformity, 11 Int’l J. Cyber Criminology 235, 235–36 (2017). ↑

- . Krupa Shah, Sexting: Risky or [F]risky – An Examination of the Current and Future Legal Treatment of Sexting in the United States, 2 Faulkner L. Rev. 193, 197 (2010). ↑

- . 18 U.S.C. § 2251(e) (2008). ↑

- . Sexting offenses may generally fall under federal child pornography law, although the exact nature of the charges is too complex to specify in this paper. Some charges involve the creation of child pornography, the transmission/ transportation of child pornography, and—in some instances—the mere receipt of child pornography. Isaac A. McBeth, Prosecute the Cheerleader, Save the World: Asserting Federal Jurisdiction over Child Pornography Crimes Committed Through Sexting, 44 U. Rich. L. Rev. 1327, 1362 (2010). While the interpretation of the law and jurisdiction vary case to case, prosecutors have found methods of applying child pornography law to sexting cases, although the fit is imperfect and the method is complex. See Id. at 1352–58. ↑

- . Bryn Ostrager, SMS. OMG! LOL! TTYL: Translating the Law to Accommodate Today’s Teens and the Evolution from Texting to Sexting, 48 Fam. Ct. Rev. 712 (2010). ↑

- . Id. at 715. ↑

- . Id. For more information on the requirements of sex offender registry, see Section III.B. ↑

- . 18 U.S.C. § 2251(a). ↑

- . Antonio M. Haynes, Note, The Age of Consent: When is Sexting No Longer “Speech Integral to Criminal Conduct”?, 97 Cornell L. Rev. 369, 369–71, 376 (2012); see also 18 U.S.C. § 2251(a) (criminalizing the visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct of a “minor”; id. § 2256(1) (defining a “minor” as “any person under the age of eighteen years,” without making exceptions for any state’s age of consent laws). Some state laws suffer from the same issue. See Emily L. Evett, Inconsistencies in Georgia’s Sex-Crime Statutes Teach Teens that Sexting Is Worse than Sex, 67 Mercer L. Rev. 405, 433–34 (2016). ↑

- . Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 8-309 (2019); Ark. Code Ann. § 5-27-609 (2019); Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-7-109 (2019); Conn. Gen. Stat. § 53a-196h (2019); Fla. Stat. § 847.0141 (2019); Ga. Code Ann. § 16-11-90 (2019); Haw. Rev. Stat. § 712-1215.6 (2019); 705 Ill. Comp. Stat. 405/3-40 (2019); La. Stat. Ann. § 14:81.1.1 (2019); Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.737 (2017); N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2A:4A-71.1 (2019); N.Y. Pen. Law § 60.37 (McKinney 2012); N.Y. Pen. Law § 235.20–.22 (McKinney 1996); N.Y. Soc. Serv. Law § 458-l (McKinney 2012); N.D. Cent. Code. § 12.1-27.1-01 (2019); 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 6312 (West 2019); 11 R.I. Gen. Laws § 11-9-1.4 (2018); S.D. Codified Laws § 26-10-33 (2019); Tex. Pen. Code Ann. § 43.261 (2019); Utah Code Ann. § 76-10-1206 (2019); Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, § 2802b (2018); W. Va. Code § 49-4-717 (2019). ↑

- . “Status offense” refers to a crime committed by a juvenile that would not have been a crime if it had been committed by an adult (such as underage drinking). See Offense, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). When status offenses are tried, the court enjoys broad jurisdictional power in sentencing and may impose lesser sentences (such as educational programs or community service) based on the understanding that the status offender is not as serious a threat to society as a “real” offender. See, e.g., Susan K. Datesman, Offense Specialization and Escalation Among Status Offenders, 75 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1246, 1247 (1984). ↑

- . 11 R.I. Gen. Laws § 11-9-1.4. ↑

- . Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-7-109. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Nonconsensual pornography laws are sometimes referred to as “revenge porn” laws due to the phenomenon of pornographic images being shared without the subject’s consent following a romantic breakup as a form of “revenge” against a person’s former romantic partner. Zak Franklin, Justice for Revenge Porn Victims: Legal Theories to Overcome Claims of Civil Immunity by Operators of Revenge Porn Websites, 102 Calif. L. Rev. 1303, 1306–09 (2014). This Comment will use the term “nonconsensual pornography” both for clarity as well as to describe a larger phenomenon of intimate photographs being shared without the subject’s consent, regardless of the situation surrounding the sharing of such images. ↑

- . Matthew Edward Carey, Nonconsensual Pornography: Prevention Is Key, 89 U. Colo. L. Rev. F. 17, 18 (2018). ↑

- . Danielle Keats Citron & Mary Anne Franks, Criminalizing Revenge Porn, 49 Wake Forest L. Rev. 345, 346 (2014). ↑

- . See Merriam-Webster, supra note 18. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See, e.g., Carey, supra note 70, at 18 (“In 1980, Hustler magazine published intimate photos of a woman that were taken by her husband during a camping trip in what was one of the first instances of widely distributed [nonconsensual pornography].”). ↑

- . Sameer Hinduja & Justin W. Patchin, Cyberbullying Research Ctr., State Sexting Laws: A Brief Review of State Sexting and Revenge Porn Laws and Policies (2015). The states that do not have sexting-specific laws, but do have revenge porn laws, include Alaska, California, Delaware, Idaho, New Mexico, Oregon, Virginia, and Wisconsin. O’Connor et al., supra note 52, at 225–29; see also Alaska Stat. § 11.61.120 (2018). For more information on nonconsensual pornography laws, see generally Carey, supra note 70 (explaining in-depth the problem with nonconsensual pornography, current laws addressing nonconsensual pornography, and future potential steps to curb the spread of nonconsensual pornography). ↑

- . States that do not have either sexting-specific laws or revenge porn laws include Alabama, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Washington, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia. O’Connor et al., supra note 52, at 225–29. ↑

- . Richard Chalfen, ‘It’s Only a Picture’: Sexting, ‘Smutty’ Snapshots and Felony Charges, 24 Visual Stud. 258, 264 (2009). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . The Court has increasingly recognized that teenagers, like adults, have a right to privacy. This indicates that the Court may be willing to extend these constitutional protections to include the act of sexting under the Fourteenth Amendment. Elizbaeth C. Eraker, Stemming Sexting: Sensible Legal Approaches to Teenagers’ Exchange of Self-Produced Pornography, 25 Berkeley Tech. L. J. 555, 585–86 (2010). ↑

- . 443 U.S. 622, 634 (1979). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . 428 U.S. 52, 74 (1976). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Linda Lowen, What Romeo and Juliet Laws Mean for Teens, ThoughtCo (Sept. 9, 2018), https://www.thoughtco.com/romeo-and-juliet-laws-what-they-mean-3533768 [https://perma.cc/NXT2-ZPHP]. ↑

- . See generally Amy Adele Hasinoff, Sexting Panic: Rethinking Criminalization, Privacy, and Consent 101–27 (Univ. of Ill. Press ed., 2015) (describing sexualization and participation, arguing that while peer pressure and society may play a role, a teenager’s choice to sext must ultimately be attributed to the teenager’s own sexual agency). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . David J. Ley, Stop Criminalizing Teens for Sexting, Psychol. Today (Nov. 8, 2015), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/women-who-stray/ 201511/stop-criminalizing-teens-sexting [https://perma.cc/A9E8-ZMYX]; Claire Meehan & Emma Wicks, Sexting: Technology Is Changing What Young People Share Online, Conversation (Dec. 12, 2017, 8:38 PM), https://theconversation .com/sexting-technology-is-changing-what-young-people-share-online-82684 [https://perma.cc/Z9L3-XMM7]. ↑

- . Planned Parenthood of Cent. Mo. v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52, 73–74 (1976). ↑

- . Raymond Arthur, Consensual Teenage Sexting and Youth Criminal Records, 5 Crim. L. Rev. 377, 380 (2018). ↑

- . Skenazy, supra note 14. ↑

- . Shah, supra note 53, at 205. ↑

- . See Ostrager, supra note 56, at 715 (“The Jacob Wetterling Act requires states to implement a sex offender registry that contains the offender’s current address. Under the Act, the offender must verify his or her address annually for a minimum of 10 years.”). ↑

- . America’s Unjust Sex Laws, Economist (Aug. 6, 2009), https://www .economist.com/leaders/2009/08/06/americas-unjust-sex-laws [https://perma.cc/ R8XP-8NDW]; see, e.g., Colorado Convicted Sex Offender Search, Colo. Bureau Investigation, https://apps.colorado.gov/apps/dps/sor/index.jsf (last visited Sept. 10, 2019) (after searching for registered sex offenders on the Colorado Bureau of Investigation website, users are provided with a “print” icon at the top of the search results). ↑

- . America’s Unjust Sex Laws, supra note 96. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. The threat of death or violent assault is not only limited to the sex offender: a study from Florida found that out of 183 families of registered sex offenders, 19 percent reported having been “threatened, harassed, assaulted, injured, or suffered property damage” as a result of sharing a home with a person forced to register as a sex offender. Justice Policy Inst., Registering Harm: How Sex Offense Registries Fail Youth and Communities 23 (2008). Studies from New Jersey and Colorado similarly found that families of juvenile sex offenders were concerned about the impact that the public registry would have on their other, innocent family members. Id. ↑

- . Monica Davey, Case Shows Limits of Sex Offender Alert Programs, N.Y. Times (Sept. 1, 2009), https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/02/us/02offenders.html [https://perma.cc/69WG-GK82]. ↑

- . America’s Unjust Sex Laws, supra note 96. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . 543 U.S. 551, 569 (2005). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 570. ↑

- . 560 U.S. 48, 80 (2010). ↑

- . 567 U.S. 460, 79–80 (2012). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . No. 16CA1289, 2019 WL 2528764, ¶ 44 (Colo. App. June 20, 2019). The Court of Appeals held that lifetime sex offender registry is “excessive” and unjust but did not offer a conclusion regarding whether lifetime sex offender registry is a cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment, nor did the court find that lifetime sex offender registry for juveniles was necessarily unjust in every situation. Rather, the court found that these sentences are unjust when applied without consideration of the fact that such sentences offer no deterrent effect or of whether sex offender registry is truly necessary to protect the public. Id. The court additionally found that there was an insufficient discovery of facts and remanded to the lower court to gather further evidence and make findings on the issue of whether lifetime registration requirement for juveniles constitutes cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. Id. ¶ 52. ↑

- . Strohmaier et al., supra note 24, at 246 (“More than 25% of study respondents who had received sexually explicit images forwarded these texts to others, and more than 33% of those who sent them reported being aware of potential legal consequences, suggesting that sexting legislation may not be a particularly effective deterrent.”). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Lawrence G. Walters, How to Fix the Sexting Problem: An Analysis of the Legal and Policy Considerations for Sexting Legislation, 9 First Amend. L. Rev. 98, 148 (2010). ↑

- . David J. Ley, We Can’t Stop Teens from Sexting, Psychol. Today (July 5, 2018), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/women-who-stray/201807/we-cant-stop-teens-sexting [https://perma.cc/DP9T-LNKP]. ↑

- . Julia Halloran McLaughlin, Crime and Punishment: Teen Sexting in Context, 115 Penn St. L. Rev. 135, 146 (2010) (“Because 56% of those sexting do not perceive the conduct as illegal, the potential risk of legal prosecution is absolutely irrelevant to their decision-making process.”). ↑

- . Jennifer A. Drobac, Age-of-Consent Laws Don’t Reflect Teenage Psychology. Here’s How to Fix Them., Vox (Nov. 20, 2017), https://www .vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/11/20/16677180/age-consent-teenage-psychology-law-roy-moore [https://perma.cc/44V8-X9Y2] (“Neuroscience and psychosocial evidence confirms that teens can make cognitively rational choices in ‘cool’ situations—that is, when they have access to information, face little pressure, and possibly have adult guidance. Teens make decisions differently in ‘hot’ situations that involve peer pressure, new experiences, and no time for reflection.”). ↑

- . Jan Hoffman, A Girl’s Nude Photo, and Altered Lives, N.Y. Times (Mar. 26, 2011), https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/27/us/27sexting.html [https:// perma.cc/NU4C-AHV5]. ↑

- . Elizabeth J. Letourneau, The Influence of Sex Offender Registration on Juvenile Sexual Recidivism, 20 Crim. Just. Pol’y Rev. 136, 147 (2009). ↑

- . This may be because an individual who is already required to register as a sex offender may feel that they have little to lose by committing additional sex-related crimes. Therefore, the potential consequences of committing sex-related crimes are less severe for individuals who are already required to register as sex offenders compared to those who are not. Id. ↑

- . See J.J. Prescott & Jonah E. Rockoff, Do Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws Affect Criminal Behavior?, 54 J. L. & Econ. 161, 161 (2011) (“We find that notification may actually increase recidivism. This latter finding, consistent with the idea that notification imposes severe costs that offset the benefits to offenders of forgoing criminal activity, is significant, given that notification’s purpose is recidivism reduction.”); Sarah Theodore, Integrated Response to Sexting: Utilization of Parents and Schools in Deterrence, 27 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol’y 365, 389 (2011). ↑

- . Lara Karaian, What Is Self-exploitation? Rethinking the Relationship Between Sexualization and ‘Sexting’ in Law and Order Times 337–51 (Renold Ringrose ed., 2015). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See supra Section I.B. ↑

- . See supra Part I (explaining that teenagers acting in sexualized ways is nothing new and is a normal part of puberty as well as sexual development). ↑

- . See supra Part I. ↑

- . See Amy Adele Hasinoff, Blaming Sexualization for Sexting, 11 Girlhood Stud. 102, 102 (2018). ↑

- . See supra Section III.C. ↑

- . See Hasinoff, supra note 128, at 102. ↑

- . See Michael Salter, Thomas Crofts & Murray Lee, Beyond Criminalisation and Responsibilisation: Sexting, Gender and Young People, 24 Current Issues Crim. Just. 301 (2013); see also Eilish O’Regan, Girls as Young as Nine ‘Sexting’ Nude Photos to Boys in Class, Independent (Feb. 23, 2017), https:// www.independent.ie/irish-news/education/girls-as-young-as-nine-sexting-nude-photos-to-boys-in-class-35475030.html [https://perma.cc/CCM2-4MH3] (“A nine-year-old girl who was sending nude photos of herself to boys in her class is a victim of the growing trend of ‘sexting’ which is now becoming the ‘norm’ among young people, it emerged yesterday.”). ↑

- . See Kath Albury, Selfies, Sexts, and Sneaky Hats: Young People’s Understandings of Gendered Practices of Self-Representation, 9 Int’l J. Comm. 1734, 1738 (2015); Nora R.A. Draper, Is Your Teen at Risk? Discourse of Adolescent Sexting in United States Television News, J. Child. & Media 221, 226–28 (2011). ↑

- . See Lenhart, supra note 24, at 4 (reporting no gendered difference for either sending or receiving sexts); Bianca Klettke, David J. Hallford & David J. Mellor, Sexting Prevalence and Correlates: A Systematic Literature Review, 34 Clinical Psychol. Rev. 44, 50–53 (2014) (finding no gender difference in sexting behavior for sending texts but reporting some gendered differences in the rate of receiving sexts); Eric Rice, Jeremy Gibbs, Hailey Winetrobe, Harmony Rhoades, Aaron Plant, Jorge Montoya & Timothy Kordic, Sexting and Sexual Behavior Among Middle School Students, 134 Pediatrics 21, 24–27 (2014) (finding no gendered difference in sexting behavior regarding sending texts, with no significant conclusions regarding gendered differences in the rate of receiving texts); Pouria Samimi & Kevin Alderson, Sexting Among Undergraduate Students, 31 Computers Hum. Behav. 230, 230–41 (2014) (finding that, after accounting for relationship status, there was no noticeable difference in sexting behaviors between males and females, but females did exhibit more apprehension in sexting and were more likely to be focused on potential negative consequences). ↑