Open PDF in Browser: Tracey E. George & Albert H. Yoon,* The Visible Trial: Judicial Assessment As Adjudication

Only a small fraction of lawsuits ends in trial—a phenomenon termed the “vanishing trial.” Critics of the declining trial rate see a remote, increasingly regressive judicial system. Defenders see a system that allows parties to resolve disputes independently. Analyzing criminal and civil filings in federal district court for the forty-year period from 1980 to 2019, we confirm a steady decline in the absolute and relative number of trials. We find, however, this emphasis on trial rate obscures courts’ vital role and ignores parties’ goals. Judges adjudicate disputes directly by ruling or effectively through other assessments of the parties’ cases. Even as their absolute and relative numbers decrease, trials remain the most visible event in trial courts. The visible trial serves effectively as a guide star. Our findings warrant a fundamental reconceptualization of litigation as primarily about educating parties rather than about trying cases. The assessment theory proposed here views adjudication as a continuous, information-disclosing process that is guided by but not destined for trial. Our evaluation and expectations of the modern justice system should be focused on the effectiveness of judges as teachers.

Introduction

Over two decades ago, leaders of the civil justice bar warned that trials were “vanishing.”[1] The American Bar Association (ABA) Section of Litigation announced in 2002 the launch of a massive multidisciplinary, multi-year project to examine the dwindling number of civil and criminal trials.[2] That same year, the ABA’s flagship journal published The Vanishing Trial as its lead article, warning that federal and state courts had experienced sharp declines in civil and criminal trials: “For a phenomenon with far-reaching implications for our system of justice, the decline in federal trials has barely registered on the professional radar screen.”[3] While a few scholars had warned of vanishing jury trials in the past, the concept that trials generally were vanishing had not gained real traction before 2002.[4]

The Vanishing Trial Project (“Project”) quickly took over the discourse, drawing immediate interest from and spawning debate among practitioners, jurists, and scholars.[5] In 2003, the ABA sponsored a two-day symposium devoted to the subject, drawing state and federal judges as well as leading lawyers from across the country.[6] The ABA Section of Dispute Resolution dedicated an issue of its magazine to the topic the following year.[7] Federal and state judges also took up the topic, offering their views in interviews, speeches, and writings.[8] Nearly every litigation-related organization—including the American Law Institute, American Trial Lawyers Association, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, state bar associations, and judicial conferences—devoted time at their annual meetings to discussion of the Project.[9]

The vanishing trial idea also inspired legal scholars and social scientists.[10] Cornell Law School recently debuted an academic journal devoted to quantitative analysis of law and legal institutions, the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, and its second issue focused on the vanishing trial. Prominent judicial and procedural scholars examined this phenomenon from multiple perspectives: state versus federal trials;[11] trials in the United States versus other countries;[12] reasons for trial displacement;[13] and the effect on particular areas of law.[14] A few examined criminal cases, but most focused on civil actions. While some writers took a descriptive rather than normative view on the declining rate of trial,[15] most adopted an implicitly,[16] if not explicitly,[17] critical view of the dwindling number of trials.[18]

The vanishing trial phenomenon has become so well-accepted today that the term is now used with little need for elaboration or citation.[19] More than fourteen-hundred law review articles cited the vanishing trial between 2002 and 2022 with sustained frequency.[20] Books have offered more extended explorations.[21] The ABA’s Project and the subsequent writing and discussion elevated the subject. No one seriously disputed that the trial, an American institution, was endangered. While the positive theory of the vanishing trial is fairly well-settled, the normative one is decidedly not.

One normative theory views infrequent trials as evidence of the degradation of the judicial system, arguing that courts have abandoned their adjudicator role.[22] The strongest form of this theory argues that trials are ultimately the most important means of providing justice, and thus their decline is a concomitant decline in the justice provided by the judicial system.[23] The moderate form views the decline in trials as a signal—perhaps even an alarm—that something is amiss.[24] These procedural and social justice scholars see possible judicial abandonment of adjudication in the vanishing trial.

A competing normative theory takes the opposite view, seeing the decline in trials as evidence that courts are less relevant as parties can make sound decisions with only the prospect of court intervention.[25] The strong version of this theory argues that parties can do an effective job forecasting litigation outcomes, thereby obviating the need for judges and juries to resolve more than a handful of representative—or bellwether—cases.[26] The moderate view acknowledges that courts play a more important role because a plaintiff (or prosecutor) could ask a court to intervene. That is, that prospect, whether raised before or after a claim (or charge) is filed, will impact parties’ actions. According to economic theorists, in many disputes, apparent adjudication does the work more effectively and efficiently—perhaps even more fairly—than actual adjudication.[27]

The justice and efficiency theories generate starkly different normative views but share an important positive core: trials are the adjudicative measure that matters. Justice theorists contend that the rarity of trial reflects an increasingly inefficient, inaccessible, and unfair judicial system in need of correction.[28] Efficiency theorists view the low trial rate as a testament to the efficacy of a common law system because the system allows parties to resolve disputes on their own.[29]

This Article contends that the emphasis on trial rate obscures the meaningful and complex informational role that trial courts play in resolving litigated disputes. The conflation of trial with adjudication perpetrates what we term the “trial myth.”

Our analysis confirms the infrequency of trials but also reveals the active part trial courts play in resolving a majority of civil as well as criminal claims. Our primary evidence includes the universe of civil and criminal cases filed in federal district court for the forty-year period from 1980 through 2019 and includes both how and when these cases resolved. While trials, whether jury or bench, occurred in less than 2 percent of civil filings, judges adjudicated over 60 percent of all filed civil actions through pretrial judgments and dismissals. We conclude that the true level of court participation likely exceeds 60 percent because settlements on average took longer to resolve than pretrial judgments and dismissals, suggesting that many settlements are responsive to information shared by courts through pretrial decisions. Criminal cases generate a similar pattern. The criminal trial rate was less than 5 percent during this period, but the duration of criminal matters that culminated in trial was only a few months longer on average than the duration of criminal matters that resulted in plea agreements. Again, as with civil actions, the criminal case evidence strongly suggests that pleas often occur in the aftermath of a judicial determination.

The well-established narrative around the vanishing trial is overly reductionist and, we argue, misguided. The focus on trials rather than the litigants produces an overly narrow view of the role of courts. The purpose of litigation is the resolution of the parties’ dispute. A litigant-focused view warrants two significant reconceptualizations. First, litigation is better understood as a continuous rather than a dichotomous process. Second, the court’s role is to actively promote the production of information between litigants, thereby fostering dispute resolution. We therefore should develop and rely on metrics tied to those features.

This Article proceeds as follows. We discuss in Part I the dominant normative theories of the vanishing trial: the justice theory (“adjudication abandonment”) and the efficiency theory (“apparent adjudication”). In Part II, drawing upon detailed data on the progress of civil and criminal actions in federal district courts, we take a closer look at the positive theory of the vanishing trial. We revisit the trend to see where we are two decades after the ABA’s Project. We also propose and apply alternative measures for determining the role that courts play in resolving claims. We offer a new framework and tools for measuring trial court effectiveness in Part III. Part IV offers concluding thoughts about the remaining questions and their importance.

I. The Vanishing Trial View of Litigation

Scholars have drawn two distinct normative positions based on the rarity of trial. One side, informed by procedural and social justice theories, works from the premise that litigants come to court seeking assistance and protection because they lack access to extra-judicial resources and because the justice system exists in part to aid the public. These justice theorists generally view trial as good. The other side, relying on economic models, works from the premise that litigants are sophisticated and draw upon their understanding of their case and the relevant law to resolve disputes on their own, when possible. Efficiency theorists generally view trial as bad. The conflicting starting perspectives of each side lead them to reach starkly divergent conclusions from the empirical evidence that trials are rare events. We refer to the justice-based theory as “adjudication abandonment” and the efficiency-based theory as “apparent adjudication” to highlight the common themes among a vast body of scholarship presenting the two counter narratives.

A. Adjudication Abandonment Theory

The justice model sees the decline of civil and criminal trials as evidence of a failed system. In an ideal world, under this theory, all litigants would have the opportunity for a trial. Indeed, Yale Law Dean Charles Clark, a leading architect of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, believed that a merits decision by a jury should be the goal of procedure.[30] Practical considerations—most notably the substantial number of filed cases relative to the number of judges as well as the availability of courtrooms—may preclude this possibility for all cases. However, it should remain a meaningful option across civil and criminal matters.[31]

The trial selection effect has consequences on both an individual and an aggregate level. Litigants who have meritorious claims but lack the resources to hold out until trial may end up with outcomes far worse than their counterparts with equally meritorious claims and more resources.[32] Accordingly, case closure without the benefit of trial may deny many litigants fair outcomes.[33] Without the benefit of trial, litigant wealth plays as much a role in determining case outcomes as do the merits of each side.[34] Collectively, this phenomenon comes at a social cost.[35]

At the aggregate level, the selection criteria for trial skews which cases resolve by trial and therefore which cases contribute to the corpus that is the common law.[36] Imagine the common law as a multidimensional canvas on which courts add incrementally with each decision. If courts chose a random sample of cases to decide by trial, their decisions, over time, would fill in a representative and substantial part of the canvas. Of course, cases decided by trial are nonrandom,[37] meaning that courts may focus on only certain parts of the canvas (such as claims that judges view as more inherently meritorious or claimants whom they favor)[38] at the expense of other parts of the canvas (such as claims and claimants against whom judges are biased or disputes where one or both litigants systematically eschew a trial outcome for financial or other reasons).[39]

Justice theorists point to many additional advantages of trial and disadvantages of alternatives. Non-trial outcomes lack the imprimatur of the courts.[40] The selection criteria that determine which litigants proceed to trial have a regressive streak because trials take time and resources which many litigants lack.[41] Trial provides a forum for debate about rights and responsibilities and a means to disclose the law and parties’ actions to the public.[42] Ultimately, trial is part of the foundation of American democracy.[43]

B. Apparent Adjudication Theory

Economic scholars have long heralded the efficiency of the common law.[44] Accordingly, cases that resolve without trial reflect litigants rationally acting in the shadow of the law—anticipating how the case would be resolved at trial and settling on those terms (adjusted for saved legal costs and discounted by the probability of success).[45] Cases that proceed to trial reflect relatively uncommon instances where existing law is unclear and for which opposing parties have an ex ante equal chance of prevailing at trial.[46] While subsequent work has challenged both the theoretical[47] and empirical[48] validity of that perspective on which disputes are selected for trial, the notion that the common law generally provides clear guidance to litigants continues to hold intuitive appeal.

In this model, cases operate in a market where litigants resort to trial when either existing precedent fails to signal a clear result given the facts of the case, or the litigants disagree over the relevant facts and hence over which prior outcome controls. This approach takes an agnostic view of the frequency of trial but recognizes that the cases that do resolve by trial shed light on the type of disputes that cannot be settled by the parties and require judicial (and even jury) intervention.[49]

Early economic models of litigation assumed that the common law—incrementally with each published decision—converges towards efficiency.[50] The private and social incentives to litigate often diverge:[51] The choice that benefits the individual litigant may differ from the choice that benefits society.[52] Early scholarship found that decisions that converge towards efficiency, taken collectively, promote social welfare,[53] while some later scholars identified conditions under which selection out of trial may reduce social welfare by discouraging certain cases from proceeding to trial while encouraging others.[54] However, the efficiency model of litigation ultimately views trial as a “failure.”[55]

C. Two Theories, One Premise

The existing spectrum of theories of trial are presented in Figure 1, which underscores the differences between them. While leading scholars disagree on the relative virtues of trial—notably Fiss[56] and Bok[57]—they implicitly share a common view that litigation culminates either in trial or settlement. This reductionist framework has endured in the literature for both proponents[58] and critics[59] of non-trial outcomes. They diverge on their interpretation of the rate of trial, with economically minded legal scholars viewing it primarily as a proxy for particularly challenging cases, and procedural and ethics scholars as a manifestation of access to justice issues. For reasons we describe in detail below, we proffer a different theory of adjudication, one that recognizes the multifaceted role that trial courts perform, of which only a fraction occurs during trial.

| Figure 1. Competing Adjudication Theories | |||

|

Adjudication Abandonment Theory |

Apparent Adjudication

Theory |

||

|

Status Quo |

Steering | Signaling |

Symbolic |

| Courts reinforce existing power structures | Courts facilitate parties’ private interactions | Courts allow parties to estimate outcomes |

Courts play little active role in dispute resolution |

II. Revisiting the Trial Court Data

The Vanishing Trial Project’s most striking and oft-cited finding was that while civil dispositions increased five-fold between 1962 and 2002, the number of civil trials decreased by 20 percent.[60] Marc Galanter, who led the substantial data analysis for the Project, reported that the civil trial rate therefore decreased from around 12 percent in the first years of the sixties to around 2 percent by the early twenty-first century. The criminal findings are almost as striking: the criminal caseload more than doubled during the same period, while the absolute number of criminal trials fell by 30 percent.[61] The criminal trial rate fell from roughly 15 percent to 5 percent.

We take both a broader and more detailed look at the trial court data. We first find that the vanishing trial trend line reaches farther back in time and continues today. Thus, federal caseload statistics confirm the conventional wisdom that trials are rare and becoming rarer.

Trials, however, represent only the proverbial tip of the iceberg of how civil and criminal cases resolve. Keep in mind that while Galanter found a meaningful drop in the number and rate of trials from 1962 to 2002, he did not find that trial was a common event at any point during the period: only twelve in one hundred civil actions and fifteen in one hundred criminal actions went to trial in 1962. To reveal more about the work of courts, we look more closely at the process from filing to conclusion of civil and criminal matters.

For our analysis, we use the Federal Judicial Center (FJC) Integrated Database (IDB). The database was created through a partnership between the FJC and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO) to track federal case filings through the trial and appellate systems. IDB contains case-level data on civil and criminal filings and terminations in the district court. The unit of analysis is the case filing, containing detailed information including the docket, court jurisdiction, date of filing and termination, nature of the suit (civil cases) or major offense (criminal cases), and disposition. To gain a fuller understanding, it helps to examine the entire universe of case filings and their resolution. For ease of clarity, we discuss civil and criminal filings separately.

Measuring the phenomenon requires a definition of what constitutes a trial. A trial is a court proceeding where the parties present evidence to secure a final judgment. A trial can be before a judge and jury or only a judge alone (i.e., a bench trial). A civil action or criminal prosecution is decided by trial when either the factfinder issues a verdict or the judge rules, before the case is submitted to the jury, that no reasonable jury could find for the opposing party and orders a directed verdict.[62]

A. Taking a Longer Look

The Project covered four decades, beginning in 1962 and ending in 2001. Galanter and others, however, noted that trial was not standard even before that time.[63] According to the AO annual reports, the civil trial rate was at 12 percent—the 1962 rate—as far back as 1950 and was only 15 percent in 1940.[64] The criminal trial rate was in fact lower in the 1940s and 1950s—hovering around 8 to 13 percent.[65] The difference is the steeply negative slope in the three decades before the vanishing trial report.

The attention to the vanishing trial and judicial concern expressed about it could have countered the decline or at least slowed it. Many of the commentators—both practitioners and scholars—set forth recommendations to encourage and facilitate more trials.[66] We find, however, that the frequency of trial in civil and criminal matters has continued its downward trend since 2002. Table 1 provides data on all federal district court cases from 1980 through 2019 using the FJC IBD.[67] We break the data out for each decade during the forty-year period and then aggregate it for the full period, reporting both the absolute number of trials as well as the percentage of filings that ended in trial. We look at federal cases because of the completeness, validity, and reliability of federal data in general and as contrasted to state data.[68] The federal data include all ninety-four district courts and thus covers the entire United States and its territories.

| Table 1. Filed Federal Cases Resolved by Trial, 1980–2019 | |||||

|

Civil Trials |

Criminal Trials | ||||

| Number of Cases Resolved by Trial | Percentage of All Filed Cases | Number of Cases Resolved by Trial |

Percentage of All Filed Cases |

||

|

1980–1989 |

94,984 | 4.20% | 67,861 | 7.76% | |

|

1990–-1999 |

64,800 | 2.69% | 58,562 |

9.13% |

|

|

2000–-2009 |

41,355 | 1.62% | 36,321 |

4.21% |

|

|

2010–-2019 |

24,188 | 0.86% | 22,704 |

2.60% |

|

| 1980–-2019 |

225,327 |

2.24% |

185,448 |

6.50% | |

| Source: Federal Judicial Center, Integrated Database, https://www.fjc.gov/research/idb. | |||||

Table 1 confirms the conventional wisdom that an extremely small percentage of filed civil or criminal cases culminate in trial and, indeed, this percentage has been steadily declining with each successive decade. Unsurprisingly, the rate of criminal trials is higher than for civil trials, given that Sixth Amendment constitutional protections afford criminal defendants the right “to a speedy and public trial.”[69] Notably, however, the relative decline in trial rate for civil cases is greater (roughly 80 percent) compared with criminal cases (roughly 20 percent).

B. Taking a Closer Look

Federal caseload statistics confirm the conventional wisdom that trials are rare and becoming rarer. Trials, however, are only the most visible substantive resolution of civil and criminal cases. To reveal more about the work of courts, we look more closely at the process from filing to conclusion of civil and criminal matters.

The FJC IDB contains case-level data on civil and criminal filings and terminations in the district court. The unit of analysis is the case filing, containing detailed information including the docket, court jurisdiction, date of filing and termination, nature of the suit (civil cases) or major offense (criminal cases), and disposition. To gain a fuller understanding, it helps to examine the entire universe of case filings and their resolution. For ease of clarity, we discuss civil and criminal filings separately.

1. Civil Case Resolutions

The AO records how each civil case resolves, assigning one of twenty-one resolutions.[70] For our time period, we exclude the eighteen observations where the resolution was “missing” or “unknown.” Table 2 provides a breakdown of each of the resolutions, grouped together into five broad categories:

Transfer/Remand: Roughly 10 percent of civil filings are transferred or remanded to another district court, a state court, or an administrative agency. In some instances, a court decides that cases filed across different jurisdictions can be consolidated and transferred to a single district judge to handle common questions of fact and law (multidistrict litigation or MDL).

Dismissal: This category represents civil filings where the court dismissed the case (not including dispositive motions to dismiss). More than one in three filed claims (35 percent) resulted in dismissal. The AO categorizes over 60 percent of dismissals as “other” which omits the specific grounds for the court dismissing the case. Close to one-third of dismissals are voluntary, in which the litigants themselves agree to dismiss the case. The remaining dismissals are due to a lack of jurisdiction or want of prosecution (e.g., the plaintiff fails to pursue the case in a timely manner).

Settlement: According to the AO, nearly 30 percent of all filed civil suits resolve through settlement reported to the court.

Judgment: This category represents actions by the court that do not require a trial but nonetheless resolve the matter for the parties. The AO lists a range of outcomes that fall within this category. The most common category—nearly half of all judgments—is a pretrial dispositive motion. One common motion is a motion to dismiss due to the plaintiff’s failure to make a cognizable claim or meet another threshold prerequisite to a viable legal action. Another is a motion for summary judgment in which the court rules that the parties agree on the material facts, and the court can decide the case as a matter of law. Default judgments—where the court typically rules in favor of the plaintiff due to defendant inaction—are common within this category, as are decisions to affirm or deny an appeal from the decision of a magistrate judge (MJ).

Trial: Jury verdicts comprise over half of trial outcomes. The judge decides the remaining matters, usually at the end of a bench trial (42 percent of trial outcomes) but also by issuing a directed verdict in a jury trial, finding that one of the parties has failed to prove their case as a matter of law (only 5 percent of trial outcomes).

Table 2 presents a more nuanced portrait of civil litigation than found in most of the scholarly debate about the merits of trial. While there may be a certain intuitive appeal to thinking of civil litigation through the lens of trials and settlement (which is comprised of everything that is not trial), this binary construct fails to capture the myriad ways in which civil litigants resolve their disputes.

Civil litigation is not simply a choice between trial and settlement. While trials clearly occur infrequently, a similar argument can also be made for settlement. That the data reveal only a quarter of all civil suits result in settlement is a lower estimate than scholars in earlier work have found.[71]

Second, Table 2 reveals that for most civil suits filed, the court provides the substantial adjudication for the parties by sharing crucial information about and assessment of their cases. Ignoring transfers and remands—which redirect the parties to a different adjudicative forum (and are captured in resolution statistics in those fora)—the courts’ actions in dismissals, judgments, and trials comprise 69 percent of all civil filings. Stated slightly differently, the court is formally adjudicating the dispute in over two-thirds of all civil filings. Although most of these outcomes do not involve adjudication by trial, they nonetheless involve adjudication by judges. Moreover, in many instances—such as when a court adjudicates motions for summary judgment—the court’s adjudication articulates its view that a trial is unnecessary because one of the parties cannot make its case rather than simply denying parties the opportunity to do so.

Returning to the issue of settlement, we posit that the settlement rate likely understates the full scope of the courts’ role in adjudicating civil disputes. While it is certainly possible that litigants can reach a settlement without the courts’ involvement, the pretrial process reflects a period during which litigants typically file motions before the court to convey information to the opposing litigant as well as the court. These information-disclosing motions include the relevance and admissibility of evidence, the scope of legal arguments, and even which parties can be named in the suit. The court makes determinations on these motions, which, even when not deciding the matter, can have a substantial effect on the parties’ perception of the case. For example, a plaintiff who loses a Daubert hearing to admit their preferred expert witness may then determine their prima facie case is weaker and will therefore decide to settle. In this instance, the resolution of the case is settlement, but the court had an active role in advancing this outcome.

| Table 2. Resolution of Filed Federal Civil Cases, 1980–2019 | ||||

| Category | Specific Resolution | Number of Filings | Percentage of All Resolutions | Percentage of All Filed Cases |

| Transfer/ Remand | Another District Court | 272,339 | 2.71% | 9.64% |

| State Court | 285,871 | 2.84% | ||

| MDL | 256,466 | 2.55% | ||

| Admin. Agency | 154,449 | 1.54% | ||

| Dismissal | Lack of Jurisdiction | 1,035,093 | 10.30% | 38.06% |

| Voluntary | 919,472 | 9.15% | ||

| Want of Prosecution | 321,306 | 3.20% | ||

| Other | 1,550,366 | 15.42% | ||

| Settlement | Settlement | 2,133,101 | 21.22% | 21.22% |

| Judgment | Appeal Affirmed (MJ) | 92,754 | 0.92% | 28.83% |

| Appeal Denied (MJ) | 50,225 | 0.50% | ||

| Award of Arbitrator | 8,211 | 0.08% | ||

| Bankruptcy Stay | 9,698 | 0.10% | ||

| Consent | 243,477 | 2.42% | ||

| Default | 570,450 | 5.68% | ||

| Pretrial Motion | 1,364,478 | 13.57% | ||

| Statistical Closing | 188,512 | 1.88% | ||

| Other | 370,301 | 3.68% | ||

| Trial | Jury | 117,852 | 1.17% | 2.24% |

| Directed Verdict | 11,821 | 0.12% | ||

| Bench | 95,654 | 0.95% | ||

| TOTAL | 10,051,896 | 100% | 100% | |

| Source: Federal Judicial Center, Integrated Database, https://www.fjc.gov/research/idb. | ||||

2. Criminal Case Resolutions

We begin our examination of criminal filings with a caveat. For obvious institutional reasons, the resolution of criminal cases differs in kind from civil cases. In civil disputes, litigants are free to resolve their disputes without consent or even input from the court, even after filing in court. In criminal matters, once a case is filed, all prosecutions require the court to preside over the resolution, irrespective of the defendant’s guilt or innocence or the prosecutor’s willingness to prosecute. Accordingly, for defendants who are ultimately convicted of a crime, court involvement is a given; the primary question is whether defendants reach a conviction through plea agreement or trial. Our data reveal that nearly all defendants choose the former, a choice that warrants closer scrutiny.

The AO records the outcomes of criminal filings, assigning one of twenty possible outcomes. The criminal data, unlike the civil data, is reported at the defendant level rather than the case level. Table 3 provides a breakdown of these resolutions, grouped into five broad categories:

Transfer/Reassignment: As is true for civil cases, federal courts transfer some criminal matters to other jurisdictions for resolution. In the case of Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 20, the defendant seeks a transfer from the current court to the court in a different location: either where they were arrested or where they are being held. Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 21 applies to instances where the defendant is seeking a transfer for trial on the grounds that the current jurisdiction prevents a fair and impartial trial. A small fraction of cases (less than one-tenth of 1 percent, that is, 0.01 percent) is reassigned to an MJ within the jurisdiction.

Dismissal: Courts dismiss about 10 percent of all criminal charges. Over two-thirds of these dismissals fall under the general category of “dismissed, or non-conviction catchall,” where the court dismisses the case with prejudice, prohibiting prosecutors from refiling the case. By contrast, about one-fifth (20 percent of all criminal charges) are dismissed without prejudice, which allows prosecutors the right to refile. The remainder are nolle prosequi dismissals, which reflect a decision on the part of the prosecutor to not drop the suit.

Miscellaneous: An infinitesimal number of cases (0.03 percent) falls within this category. The most common form are cases deemed “statistically closed” which refers to cases that were stayed pending action in another forum.

Plea Agreement: This category represents the modal outcome for criminal cases. Over 80 percent of criminal case filings result in a plea agreement. Pleas are effectively guilty pleas. That is, the vast majority of plea agreements include the defendant entering a plea of guilt to one or more criminal charges. A small number are pretrial diversions where the defendant accepts culpability for their actions and is allowed to undergo alternatives to spending time in jail or prison. The remainder are nolo contendere pleas, where the defendant, with the court’s permission, accepts conviction without accepting or denying responsibility for the charges.

Trial: This remaining category takes many forms. Pursuant to defendants’ constitutional rights, roughly 80 percent of trials are jury trials. The data also reveal that juries find defendants guilty 84 percent of the time. Bench trials account for close to 20 percent but result in a guilty verdict somewhat less frequently than jury trials (66 percent). A small fraction of criminal trials (less than 0.02 percent of all trials) qualified for this category due to the defendant’s mental health.

In the criminal context, defendants, once charged with a federal crime, face three possible outcomes: conviction, acquittal, or dismissal. The odds of conviction are close to nine out of ten (88 percent of all defendants are convicted). Approximately 9 percent of defendants have their charges dismissed. Less than 1 percent of defendants are acquitted.

Our data reveal that, conditioned on a U.S. Attorney’s office filing charges against a defendant in federal district court, the defendant faces a likely conviction. Taking the categories together—and excluding transferred and reassigned cases—prosecutors achieve a criminal conviction nearly 90 percent of the time. This finding is consistent with scholarship that concludes that federal prosecutors are focused primarily on high conviction rates.[72] Our data naturally exclude instances where the defendant is arrested, but the U.S. Attorney’s office decides against filing charges as such events do not culminate in any court filing.

It bears noting that, at least in federal court, civil litigants face different financial constraints than criminal defendants. Civil litigants of modest means may find the costs of litigating their claim—however meritorious—exceeds their ability or willingness to finance it. Moreover, most civil causes of action do not come with constitutional guarantees of legal representation. Conversely, for federal criminal cases, defendants who cannot afford legal representation are typically afforded the services of a federal public defender, whose reputation is held in high regard, comparable to federal prosecutors and above those of the private criminal defense bar.[73] Studies show that most federal criminal defendants receive court-appointed counsel.[74] Federal criminal defendants who accept a plea agreement presumptively prefer doing so over proceeding to trial, and the availability of quality legal representation suggests that litigation resources are not central to this decision.

| Table 3. Resolution of Filed Federal Criminal Cases, 1980–2019 | ||||||

|

Category |

Specific Resolution | Number (Defend-ants) | Percentage of All Resolutions |

Percentage of All Resolutions |

||

|

Transfer/ Reassign-ment |

Rule 20(a)/21 | 28,964 | 1.00% | 1.01% | ||

|

Reassigned to MJ |

28 |

0.00% |

||||

|

Dismissal |

Dismissed or Non-Conviction Catchall |

229,612 |

7.96% |

10.37% |

||

|

Nolle Prosequi |

4,632 |

0.16% |

||||

|

Dismissed Without Prejudice |

64,763 |

2.25% |

||||

|

Miscellaneous |

NARA Tiers I & III |

17 | 0.00% | 0.12% | ||

|

Statistically Closed |

3,523 |

0.12% |

||||

| Dismissal Superseded | 47 |

0.00% |

||||

|

Plea |

Pretrial Diversion |

17,509 |

0.61% |

|||

| Nolo Contendere | 16,596 | 0.58% |

82.01% |

|||

|

Guilty Plea |

2,331,093 | 80.83% | ||||

| Trial | Acquittal – Bench | 12,937 |

0.45% |

6.50% |

||

|

Acquittal – Jury |

23,418 | 0.81% | ||||

| Conviction – Bench | 24,573 |

0.85% |

||||

|

Conviction – Jury |

121,091 | 4.20% | ||||

| NG – Mental Illness – Bench | 461 |

0.02% |

||||

|

Guilty but Mental Illness – Bench |

66 | 0.00% | ||||

| NG – Mental Illness – Jury | 58 |

0.00% |

||||

|

Guilty but Mental Illness – Jury |

37 | 0.00% | ||||

| Mistrial | 4,692 |

0.16% |

||||

| TOTAL | 2,884,117 | 100% |

100% |

|||

| Source: Federal Judicial Center, Integrated Database, https://www.fjc.gov/research/idb. | ||||||

3. Duration and Appeal Rates of Cases by Resolution

The prior Section reveals that courts play an active role in resolving litigated disputes for both civil and criminal cases filed in federal district court. This finding is particularly surprising for civil cases; for criminal cases, this finding is less surprising given the court’s essential role not just in trials, but in any outcomes resulting in a conviction, which represent the predominant outcome in criminal filings.

We can further refine the results by considering two salient aspects of the litigation: the time from filing to resolution in the trial court (duration) and the probability of post-trial judicial process (rate of appeal). Duration and rates of appeal are relevant metrics when evaluating the resolution of claims because they serve as credible proxies for litigant experience. The maxim “justice delayed is justice denied” suggests that the quality of a legal outcome is a function, at least in part, of the time taken to reach the outcome. Holding outcomes equal, most parties would prefer to achieve an outcome earlier rather than later, given the costs of legal representation and of uncertainty. The rate of appeal, by contrast, is a more direct measure of litigants’ satisfaction with the resolution of their case. The higher the rate of appeal, the more likely that one litigant (or even both) objects to the resolution.

| Table 4. Federal Civil Litigation Duration and Appeal Rates, 1980–2019 | |||

| Resolution Category |

Number of Civil Filings |

Litigation Duration (Years) |

Percent Appealed |

| Transfer/ Remand |

969,125 |

0.64 |

2.22% |

|

Dismissal |

3,826,237 | 0.93 |

7.15% |

|

Settlement |

2,133,101 | 1.25 |

1.40% |

| Judgment |

2,898,106 |

0.956 |

14.05% |

| Trial |

225,327 |

2.31 |

30.38% |

| Source: Federal Judicial Center, Integrated Database, https://www.fjc.gov/research/idb. | |||

While one would expect that the duration of a civil case would depend on its resolution, Table 4 reveals that the variation is smaller than one might expect. The duration ranges from slightly more than seven months for transfers or remands to two and a half years for trials. Notably, the categories of dismissals, settlements, and judgments, which collectively comprise 88 percent of all resolutions, are resolved on average between eleven and fifteen months. The similarity in duration across these three forms of resolution suggests that they do not map neatly along a temporal dimension. In the data, we were able to find cases of dismissal, settlement, and judgment that occurred the same month as filing, as well as those that took more than five years to resolve.

Trials reflect a higher mean duration (2.3 years) and median duration (1.7 years) than the other forms of resolution. Looking separately at jury and bench trials, we find that the former took longer on average (2.8 years) than the latter (2.3 years). We also observed a wider distribution of duration for trials than for other forms of resolution. Trials in the 95th percentile of duration exceeded ten years; at the same time, 25 percent of trials concluded within fourteen months of filing.

Appeals reveal greater differentiation across the types of resolutions. While every form of resolution generated appeals—including instances where the parties reached a settlement[75]—the highest rates of appeal occurred in instances where the court made a procedural or substantive determination in the case. Litigants appealed dismissals, which include a failure to advance their claims, 8 percent of the time. Appeals more commonly arose from resolutions where the court provided a substantive determination. Among the judgment category of resolutions, litigants rarely appealed default judgments (less than 1 percent) but appealed over a fifth (22 percent) of granted pretrial dispositive motions. Among trials, jury (30 percent) and bench (31 percent) trials generated similar rates of appeal as did the smaller set of directed verdicts (33 percent).

Among criminal cases, Table 5 reveals that plea agreements take less time on average to complete than trials. However, pleas still require, on average, three-quarters of the time needed to reach a trial verdict, representing smaller time savings (about five months) than most would expect. Moreover, the data reveal that the distribution of the time to enter pleas substantially overlaps with the distribution of time to trial outcome. For example, a closer look at the data reveals that the median duration of a trial was seven months, while for pleas, the median was five months. While a fair number of pleas resolved quickly—for example, within a month of the charges being filed—over 5 percent of pleas occurred after two years had passed since the criminal filing, a duration more than twice that for a criminal case that goes to trial.

Dismissals took the longest time on average to resolve in criminal matters—longer than a completed trial. This result may seem initially surprising. However, courts are dismissing charges against defendants only after prosecutors have proven unable to substantiate the charges brought against the defendant.

As with civil litigation, criminal appeals show greater variance by resolution type than criminal trial duration. Table 5 shows the significant difference between the likelihood of appeal from plea agreements and from trial verdicts. Plea agreements, like civil settlements, may seem an unlikely source of appeals. However, defendants can appeal a plea bargain under limited circumstances, such as a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel[76] or of prosecutorial misconduct.[77] Both give rise to potential violations of defendants’ constitutional rights.

Among trials, the 22 percent appeal rate masks considerable differences between jury and bench trials; defendants appeal in 30 percent of jury trials but only 8 percent of bench trials. This difference is even more noteworthy given that jury trials take on average thirteen months to complete, compared with five months for bench trials. Stated another way, jury trials take more than twice as long as bench trials to complete while generating appeals at three times the rate. Of course, the selection into these two trial paths is nonrandom, which may reflect differences in procedural and substantive complexity. At the same time, it raises the question whether some of the disparity is attributable to institutional differences between jury and bench trials, separate from potential selection into those two distinct types of trial.

Taken together, civil and criminal trials generate a higher percentage of appeals than any other form of resolution. While proponents of trial extol the virtues of litigants having their day in court,[78] the rate of appeals reveals that many litigants dislike the outcome. There are several possible explanations for heightened rates of appeals for trials, namely that trial typically generates a comprehensive record on which litigants can file an appeal. We are agnostic as to the merits underlying any appeal, but we note that whatever the justification for trials, higher levels of litigant satisfaction do not appear to be one of them.

III. An Assessment Theory of Adjudication

Our findings confirm the conventional wisdom that trials are increasingly rare outcomes for civil and criminal cases filed in federal district court, but more importantly, that courts adjudicate many of these disputes prior to trial. The civil data makes this finding expressly clear through the prevalence of dispositive motions; the criminal data, while more nuanced, provides compelling evidence that courts, through adjudicative motions, play an active role in helping prosecutors and defendants reach plea agreements. Previous scholars have advocated greater empirical inquiry into the litigation process.[79] Our analysis of federal cases presents a different litigation landscape from prior studies in which the majority of cases “settle without a definitive judicial ruling.”[80]

Our findings generate several implications for our conception of the role of courts. First, these findings suggest that a more helpful analytic framework to study litigation is as a series of continuous outcomes rather than a binary one of trial versus non-trial. Second, courts promote the flow of information between litigants, thereby fostering the resolution of disputes in whatever form it takes. Finally, the modern, professionalized federal judiciary has developed a number of tools that maximize its capacity to evaluate and educate parties in ways that reflect procedural justice principles as well as efficiency goals.

A. Adjudication as a Continuous Measure

Taken together, our analysis of outcomes in federal district court suggests that the trial versus plea/settlement typology is a coarse and ultimately inaccurate measure to understand litigation outcomes. This binary construct suggests that courts are actively involved in trials but not pleas or settlements. The error in such a perception is readily apparent in our examination of civil cases. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of civil cases resolve through judicial action whether it be dismissal of the claim (35 percent), a judgment of the court (27 percent), or trial (2 percent). The misperception is more subtle for criminal cases, as courts effectively sign off on all criminal filings, whether they be dismissals (9 percent), pleas (85 percent), or trials (5 percent).

The active role performed by courts outside of trial is supported by the time taken to resolve a claim. For civil filings, trials take on average two and a half years to complete, longer than all other forms of resolution. At the same time, dismissals (0.90 years) and judgments (1.06 years) each average one year to resolve. Dismissals and judgments, by definition, require adjudication by the court.

With respect to settlement, litigants could, in theory, achieve this outcome without any court involvement. The average time to settle (1.26 years), however, exceeds both dismissals and judgments. If civil cases share common characteristics regarding court involvement, the longer duration of settlements strongly suggests that parties reach this resolution in the aftermath of a court adjudication that motivates one or both parties to settle.

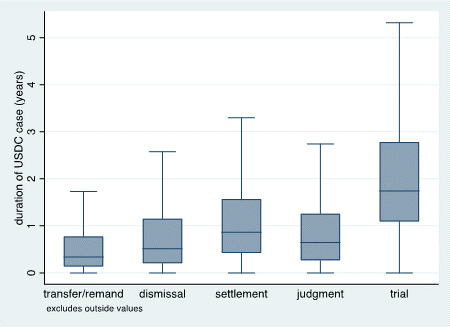

The data suggest that these differences in duration by resolution are more nuanced than at first impression. Viewing them from the perspective of means, differences in any pairwise comparison among the five outcomes are statistically significant. Boxplots of these outcomes, however, reveal considerable overlap. Figure 2 shows a boxplot for each of the civil case resolution types. While trials have the longest median (1.74 years) of all resolutions, their interquartile range (25th = 1.09; 75th = 2.78) overlaps the most with settlement (25th = 0.42; 50th = 0.86; 75th = 1.57) and to a lesser extent with judgment (25th = 0.27; 50th = 0.63; 75th = 1.25). Among the four non-trial resolutions—transfer/remand, dismissal, settlement, and judgment—the interquartile ranges overlap considerably with one another.

Figure 2. Boxplot of Duration of Federal Civil Cases by Resolution Type, 1980–2019

Criminal cases provide evidence for comparable court involvement for both pleas and trials. While pleas on average take less time (nine months) than trials (fourteen months), the difference (five months) is smaller than one might expect. Figure 3 reports the range of resolutions in criminal cases and demonstrates these differences in median duration are smaller across resolution type compared with civil filings. More significantly, the interquartile ranges for each resolution type overlaps with those of every other resolution type. The interquartile range for trials (25th = 0.33; 50th = 0.59; 75th = 1.09) fits entirely within the interquartile distribution for dismissals (25th = 0.16; 50th = 0.42; 75th = 1.43). While the entire distribution of time to resolution by plea shifts down and is also tighter, the interquartile distribution for pleas (25th = 0.25; 50th = 0.45; 75th = 0.82) still overlaps significantly with the distribution for trial. If court participation in criminal cases is at least as active as that in civil cases (and we expect it is even greater), then our numbers suggest that criminal pleas, like settlements in civil cases, occur not in the absence of court adjudication, but because of it.

Figure 3. Boxplot of Duration of Federal Criminal Cases by Resolution Type, 1980–2019

Looking at the duration of civil and criminal cases together, we posit that the data strongly suggest that courts are actively involved in helping a large fraction of litigants in both civil and criminal cases resolve their cases. The only difference is the form of this resolution. In the case of trials, the verdict is an adjudication that resolves the claim (at least at the district court level). In the case of settlements or pleas, the court adjudication prompts the parties to reach a mutually acceptable resolution. The true level of court involvement must be higher, as filings resulting in either settlements (civil) or pleas (criminal) mask likely court adjudication along the way.[81] The courts’ dynamic and iterative role in resolutions outside of trial reveals that viewing litigation through the binary, settlement-trial framework is both misleading and unhelpful.

B. Courts as a Mechanism for Generating Information

Our analysis provides evidence for the following two points. First, courts are actively involved in the resolution of civil and criminal matters, even outside of trial. Second, while relatively infrequent compared to other forms of resolution, trials on average take longer to conclude than other forms of resolution.

This evidence, we contend, points to the informational role that courts play in promoting the resolution of disputes, whether by trial or other means. That judges spend much of their time managing cases, not merely deciding them, is well established.[82] A central challenge of an adversarial system is the informational asymmetry that exists between the litigants (and between the litigants and the judge). Opposing sides have different conceptions of the underlying facts and the relevant law influenced by their private information of the facts and their own human biases.[83] The asymmetry occurs because each side privately knows of evidence supporting their versions of the facts and law and are less aware of evidence supporting the opposing side’s version.

At the start of litigation, opposing litigants typically hold different views of the case before them. They may disagree on the facts; they may disagree on the law; they may disagree on both. The adversarial system—as in the United States—encourages these disagreements, tasking the lawyer(s) on each side with presenting the strongest argument on behalf of their clients, not the opposing litigant. These differences can emerge in multiple ways. For example, opposing litigants (through their lawyers) may agree on the facts, but disagree on their understanding of the applicable law. Conversely, they may agree on the applicable law, but disagree on the facts. Scholars attribute differences in priors that litigants hold to asymmetric information[84] and divergent expectations.[85]

Even when litigants act in good faith to reach what they believe to be fair results, human biases may compel them to draw overly optimistic inferences when interpreting the facts and law, even in instances when the parties agree on the relevant facts and law.[86] The resulting biases are often difficult to displace and call for adjudication, which, as our data shows, the courts can provide through their motions practice.

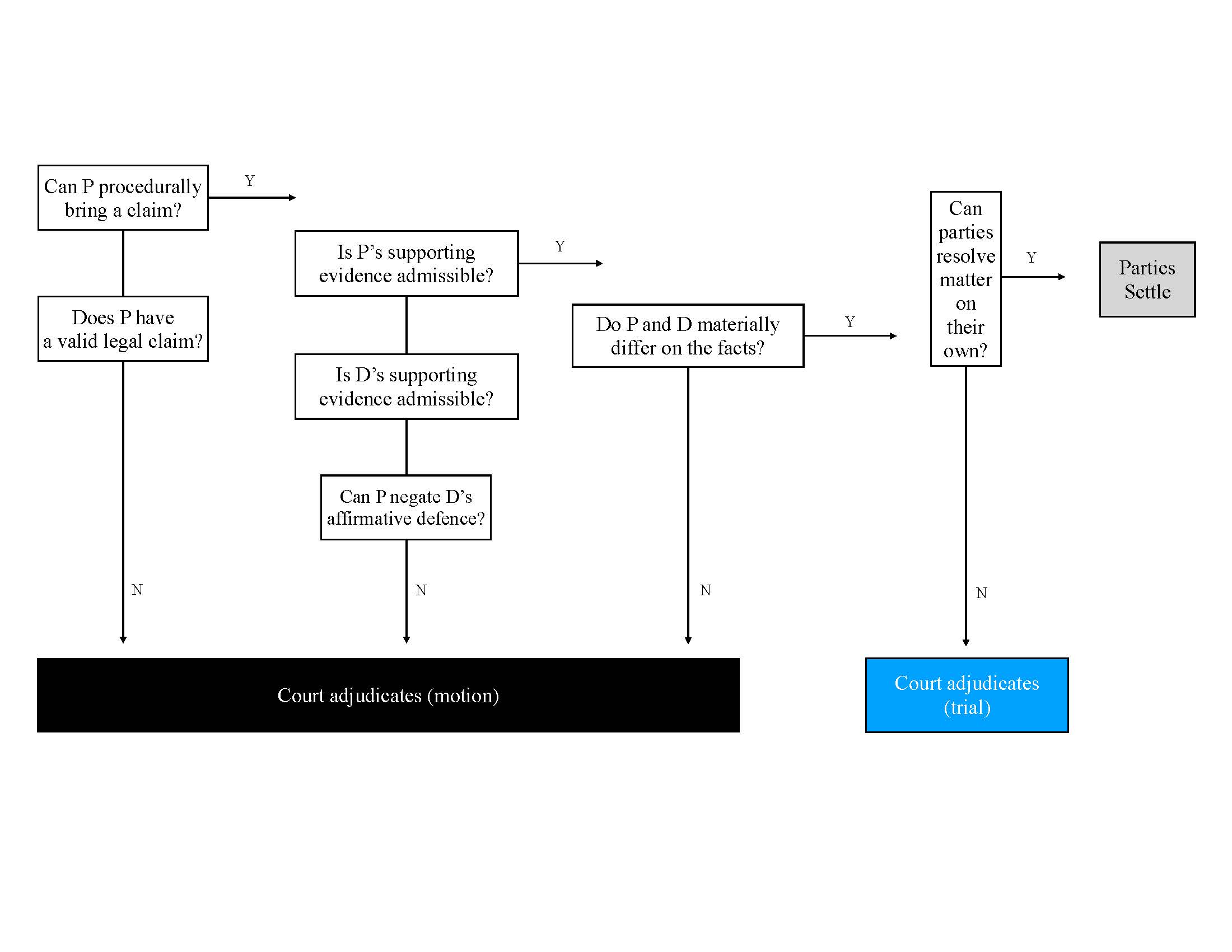

Figure 4 captures how courts facilitate the flow of information between litigants. At the time of filing, litigants are typically the least informed and have their highest level of informational asymmetry. Each side believes that the facts and the law favor their position. At the same time, each litigant’s view is limited, lacking the information that only the opposing litigant possesses. The plaintiff files suit against the defendant because their views sufficiently diverged to preclude a prior settlement (or plea).

Figure 4. Spatial Models: How Courts Generate Informational Flow Between Litigants

At the filing stage of litigation, the information the parties seek may be existential to the filing. Are there procedural grounds that preclude the plaintiff from bringing the claim? For example, is the suit time-barred? Does the plaintiff have standing to bring the suit in the first place? Separately, the plaintiff may be seeking a remedy that the law cannot provide, for example, where the defendant’s alleged conduct, however immoral, does not give rise to a legal cause of action. The court decides these questions through a motion, typically through a defendant’s motion to dismiss. Such a motion, if successful, will dispositively resolve the dispute.

For cases that proceed to the discovery stage, each litigant learns of added information that each is compelled to provide. This learning informs each side of the provable facts and applicable law, allowing them to update their prior assessment of the case. The court plays an integral role during discovery, determining what evidence is relevant and admissible. The court may exclude evidence that litigants seek to admit or, conversely, admit evidence that litigants seek to exclude. The court’s determinations at this stage may favor one side or the other, such that it may encourage parties to settle the case. Or, based on this new information, it may compel one of the litigants to file a dispositive motion, such as a motion to dismiss.

Following discovery and before trial, one or both litigants may contend that they agree to all material facts of the case and file a motion for summary judgment before the court. If the court denies the motion, the parties either continue to negotiate a settlement or proceed to trial. By granting the motion, however, the court will adjudicate part or the whole of the dispute, providing resolution for those issues.

Information is central to litigation, as reflected in Figure 4. Litigation promotes the flow of information between the plaintiff or prosecutor and the defendant. Courts play an active, iterative role in that process. This iteration explains the overlapping time periods among the different forms of resolution for both civil and criminal filings. By extension, Figure 4 also helps explain why trial rates are a blunt—and ultimately misleading—gauge of the role of courts. Although ignored in this model, the federal data show that civil disputes are frequently resolved through a dispositive motion, such as a motion to dismiss or a motion for summary judgment. Resolutions of this type usually occur more quickly than a trial would; delaying the same outcome until trial ultimately does not serve the parties’ or the system’s interests.

More importantly, viewing litigation as a mechanism to promote the flow of information between litigants prioritizes the litigants’ shared understanding of the case over the form of resolution. Some litigants reach this shared understanding prior to trial through a settlement or plea. Other litigants require judicial adjudication, whether through a dispositive motion or a trial itself. There is nothing inherent about trials that justifies privileging trial over other forms of dispute resolution. This is particularly true for litigants who have limited means to pay for extended litigation or an urgent need for an answer.

This Section thus far has ignored the role that litigant resources play in litigation outcomes. There is abundant evidence showing the heterogeneity of lawyer ability and its direct translation into client outcomes.[87] These differences vary by area of law and are particularly acute where disparities in resources are most persistent.[88] Many litigants face these resource constraints, and it is clear how these disparities influence lawyer selection, which then can affect client outcomes. That said, these resource asymmetries exist at every stage of litigation, and there is no reason to think that they are unique to the trial stage. Merely increasing the number of judges to allow more trials, as some have advocated, would not remedy the attorney asymmetry problem.[89]

We contend that a more helpful way to view litigation—both civil and criminal—is as a continuous process by which litigants seek to resolve their disputes and interact iteratively with the court. The court adjudicates matters big and small, promoting an informed resolution of these disputes while rarely going to trial.[90]

C. Judges as Evaluators and Educators

We propose an alternative to the adjudication abandonment and apparent adjudication theories: adjudication as assessment. Our assessment adjudication theory draws on the work of social psychologists who have identified the procedural elements that individuals associate with a fair process: an opportunity to express their views, a consideration of those views, a visible commitment to equity, and respectful treatment.[91] We also build on the work of economists who have identified circumstances when rational settlement processes are undermined due to informational asymmetries.[92] An assessment adjudication theory positions trial judges and courts at the center of dispute resolution.

Courts play a vital role in our society: educating litigants, evaluating arguments, and engaging with the public. The parties learn, for example, whether the claims raise cognizable legal questions, whether they can be resolved by this governmental body, which theories have merit, what evidence can be used to prove or disprove claims, and the persuasiveness of their cases. Each of those judicial roles are valuable. Each contributes to resolution of the dispute. Each provides an opportunity for the parties to be heard and to engage in Bayesian updating.

Our theory avoids the categorical view of trial taken by the strong forms of apparent adjudication and adjudication abandonment. Our theory embraces the court’s role in providing information but is agnostic as to the preferred mechanism by which it does so. Accordingly, a trial is neither the desired nor disfavored outcome. The purpose of formal litigation is to generate information that parties otherwise could not attain. One source of disclosure can come from the disputants themselves through pretrial discovery. Even discovery, however, is a court-mandated and court-facilitated process. The other source of information comes from the courts when deciding questions of law as well as questions of fact that the parties on their own cannot agree upon.

| Figure 5. The Spectrum of Adjudication Theories | ||||

|

Adjudication Abandonment Theory |

Assessment

Theory |

Apparent Adjudication Theory | ||

|

Status Quo |

Steering | Evaluating, Education, and Engaging | Signaling |

Symbolic |

| Courts reinforce existing power structures | Courts facilitate parties’ private interactions | Courts serve continuous informational and credible advisory roles | Courts allow parties to estimate outcomes |

Courts play little active role in dispute resolution |

Looking at litigation through an informational lens situates trial as simply one of many mechanisms by which the court can provide information to litigants. Our approach neither privileges nor denigrates trials. The goal of litigation is not trial per se or any specific form of resolution, but rather an equitable resolution of a dispute. Under this framework, trial is no more than a stage on a continuum of adjudicative measures that differ in procedural form but serve a common function.

In a world of limited resources and bounded human capacity, the federal judicial system can be a valuable forum for disputants. Federal courts are engaged in experimentation and innovation to meet the needs of parties in a world where courts are highly leveraged because of the large number of claims and claimants, where disputes are becoming increasingly complex and large, and where the expectations for justice and efficiency are high. The innovations may be local or national, procedural or substantive. To illustrate this point, we briefly consider a few examples: district experimentation, creative motions practice, Article I judges, and multidistrict litigation (MDL).

Federal districts are adopting various tactics that are responsive to their workload and context. We find that court jurisdictions, such as the Southern District of New York and Southern District of Ohio, differ from one another in their practices. These variations in practice undoubtedly stem in part from variations in docket, namely the types of cases filed. As part of our analysis, not reported in this Article, we ran regressions to examine the factors that influenced how filed cases resolved and whether they were appealed, controlling for the jurisdiction in which the case was filed, among other controls. We found significant differences across the ninety-four federal jurisdictions. This finding, while ancillary to our main point, provides evidence that distinctions across—and within—courts warrant closer examination as part of a study of local practices to achieve better engagement with parties.

Courts are also using procedural tools to achieve different ends. A promising research avenue from the present dataset is to better understand the role of motions in the resolution of civil and criminal disputes. Scholars have noted that our understanding of courts depends on the sources examined.[93] The FJC IDB, for all its virtues, reports only those adjudicative motions that resolve the dispute. The duration of settlements (civil) and pleas (criminal) strongly suggests courts are deciding motions that, while not dispositive, facilitate resolution.[94] A closer look at the docket sheets will provide insight into the timing of these motions and how they vary across and within courts. Given the increasing infrequency of trials, a more holistic approach can improve our understanding of the courts.

District courts have turned to MJs to not only increase their assessment capacity but also to diversify it. In another work with Christy Boyd, we have demonstrated that federal district courts have expanded their capacity to evaluate disputes and to educate and engage with parties through the expanding and evolving role of MJs.[95] MJs, who now account for nearly half of trial judges in federal districts, play meaningful roles in civil and criminal litigation. In many districts, MJs hold pretrial conferences and resolve preliminary motions, issue reports and recommendations on dispositive motions, and serve other roles—formal and informal—that expand district court capacity to listen to and advise parties. While MJs generally cannot issue final orders without party consent, they are well suited to the assessment role in jurisdictions where they are well integrated into the court’s work.[96]

Federal district courts have also increased their decision-making capacity through MDL.[97] Since its creation in 1968, the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (MDL Panel) has transferred nearly half-a-million factually related actions filed in different federal districts to a single judge in one federal district for consolidated pretrial litigation.[98] Because the lawsuits are among the most high-profile federal civil actions, their dispositions influence the public’s perception of the civil justice system and impact the development of public policy in the related substantive and procedural areas of law. The MDL process has made it possible for the federal trial courts to provide meaningful consideration and deliberative resolution of disputes that involve several hundred or several thousands of claims and individuals. While few of the underlying disputes go to trial, MDL transferee judges have developed and heard bellwether trials as a means to gain, for all parties, the advantages of trial while limiting the expenditure of resources to one or a few cases.[99] The MDL Panel also illustrates the development of special assignment courts as a new mechanism for addressing the demand for dispute resolution in the federal courts.[100]

IV. Concluding Thoughts

The trial is a definitively American institution.[101] The American legal system is widely recognized as the most adversarial in the world.[102] It is also distinctive among adversarial systems in its degree of reliance on juries: American courts use juries more frequently than even the British, who invented the jury. Trials have captured the public’s attention and imagination.[103] American popular culture has venerated the trial.[104] Memorable Oscar-winning performances celebrate the trial and the trial lawyer.[105] Most attorneys can quickly list their favorite trial movie, television show, podcast, or book. Yet even though the trial is a hallmark of the American justice system, it is not necessarily the best way to measure the system’s work.

Trial itself was never the true goal of the modern American justice system.[106] Thus, the number or rate of trials cannot be the central diagnostic tool for assessing the efficiency or fairness of the system. We contend that trial is still essential as the guide star of the judicial process, if not as the destination.[107] We agree then that trial is central to adjudication, but we disagree that its measurement necessarily tells us that much.

The rarity of trials is both documented and misunderstood. Our close examination of thirty years of federal civil and criminal litigation reveals that judges play an active and iterative role in helping parties understand, evaluate, and resolve their disputes. Judges adjudicate a plethora of issues, both procedural and substantive, that resolve disputes directly or indirectly. These findings warrant a reconceptualization of litigation as a process in which the court’s objective is to provide active assessment through various forms of adjudication, of which trial is only one.

The trial myth undermines the judicial system as well as efforts to reform that system. By focusing on the costs and benefits of trial, we fail to consider whether courts are fulfilling their function of educating and advising parties without bias or delay across the range of disputes. Over the past eight decades, federal judges have rarely relied on trial to fulfill their adjudicative function.[108] We contend that it is time to move past a view of trial, or more accurately of its absence, as the measure of the justice system’s work.

**George is Vice Provost for Faculty Affairs, Charles B. Cox III & Lucy D. Cox Family Chair in Law & Liberty, and Professor of Political Science, Vanderbilt University. Yoon is Professor and Michael J. Trebilcock Chair in Law and Economics, University of Toronto Faculty of Law. The authors would like to thank Matthew Marchello, Michelle Augustine, and Toni Cross for excellent research assistance. The authors are grateful for the helpful feedback provided by Ben Alarie, Abdi Aidid, Christy Boyd, Jonathan Cardi, Ed Cheng, Paul Frymer, Andrew Green, Mitu Gulati, Chris Guthrie, Gbemende Johnson, Anthony Niblett, Adriana Robertson, and Michael Trebilcock. Any remaining errors are our own.

- See Patricia Lee Refo, The Vanishing Trial, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. v, at v (2004) (explaining the genesis of the Vanishing Trial Project). ↑

- See Marc Galanter, The Vanishing Trial: An Examination of Trials and at Related Matters in Federal and State Courts, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 459, 459 n.* (2004). ↑

- See Hope Viner Samborn, The Vanishing Trial: More and More Cases Are Settled, Mediated or Arbitrated Without a Public Resolution. Will the Trend Harm the Justice System?, A.B.A. J., Oct. 2022, at 25. ↑

- Searches on major databases reveal that infrequent trial became synonymous with “vanishing trial” only after the ABA’s Project. For earlier uses, see Raymond Moley, The Vanishing Jury, 2 S. Cal. L. Rev. 97 (1928); Albert W. Alschuler, Foreword to Vanishing Civil Jury, 1990 U. Chi. Legal F. 1. ↑

- See Patricia Lee Refo, The Vanishing Trial, 30 Litig. 1, 1 (2004) (reporting, as the chair of the ABA Litigation Section, that “we touched a nerve. The Project spawned a blizzard of publicity in both the legal and mass media”); Adam Liptak, U.S. Suits Multiply, but Fewer Ever Get to Trial, Study Says, N.Y. Times (Dec. 14, 2003), https://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/14/us/us-suits-multiply-but-fewer-ever-get-to-trial-study-says.html [https://perma.cc/285G-863F]; Patti Waldmeier, The Decline and Fall of the American Trial, Fin. Times, Jan. 5, 2004, at 9; Oprah and the Vanishing Trial, Chi. Trib. (Aug. 18, 2004, 12:00 AM), https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2004-08-18-0408180169-story.html [https://perma.cc/B2WP-R7MZ]. ↑

- See Stephanie Francis Ward, ‘Vanishing Trials’ Issue Won’t Go Away: Conference Seeks Reasons, Solutions for Decrease, A.B.A. J. E-Rep. (Dec. 19, 2003) (describing the event); Refo, supra note 5, at 1 (reporting that the vanishing trial “has been and will continue to be the subject of follow-on conferences hosted by bar groups across the country”). ↑

- See generally Focus: The Vanishing Trial, 10 Disp. Resol. Mag. 3–6 (2004). ↑

- See, e.g., Patrick E. Higginbotham, Judge Robert A. Ainsworth, Jr. Memorial Lecture, Loyola University School of Law: So Why Do We Call Them Trial Courts?, 55 SMU L. Rev. 1405, 1423 (2002) (reprinting Fifth Circuit Judge Higginbotham’s endowed lecture at Loyola University School of Law, an updated version of his American Law Institute address, in which he explores the vanishing trial and makes the case that a “well conducted trial is [the justice system’s] crowning achievement”); Nathan L. Hecht, The Vanishing Civil Jury Trial: Trends in Texas Courts and an Uncertain Future, 47 S. Tex. L. Rev. 63 (providing a Texas Supreme Court justice’s view on the phenomenon at the state level); William G. Young, An Open Letter to U.S. District Judges, 2003 Fed. Law. 30, 30 (providing the view of the Chief Judge of the District of Massachusetts that the jurists themselves should own responsibility for countering the decline); Judges’ Views on Vanishing Civil Trials, 88 Judicature 306, 306–08 (2005) (featuring commentary from U.S. District Court Chief Judge Mark W. Bennett (N.D. Iowa), Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Margaret Downie, and Alaska Superior Court Judge Larry C. Zervos). ↑

- See, e.g., Ad Hoc Comm. on the Future of the Civ. Trial of the Am. Coll. of Trial Laws., The “Vanishing Trial:” The College, the Profession, the Civil Justice System, reprinted in 226 F.R.D. 414, 417 (2005) (observing “[t]he number of civil trials in federal court over the 40 years from 1962-2002 has fallen, both as a percentage of filings and in absolute numbers. . . . These numbers are particularly startling in light of the enormous increase in litigation over the same 40-year period”); Alex Sanders, former C.J., S.C. Ct. App., and former President, Coll. of Charleston, “Ethics Beyond the Code: The Vanishing Jury Trial, Address to the American Trial Lawyers Association” (Dec. 2, 2005); see also John W. Keker, The Advent of the ‘Vanishing Trial’: Why Trials Matter, Champion, Sept./Oct. 2005, at 32–33 (arguing “[j]udges led the change to fewer trials and now they regret it”). ↑

- See, e.g., Jennie Berry, Introduction to the Symposium, 57 Stan. L. Rev. 1251, 1251 (2005) (introducing a special issue of the Stanford Law Review “explor[ing] major changes in the civil litigation landscape” and responding to the Project’s findings); Marc Galanter, The Hundred-Year Decline of Trials and the Thirty Years War, 57 Stan. L. Rev. 1255, 1255 (2005) (presenting his vanishing trial findings as the focal presentation and article in this special symposium issue). ↑

- See Brian Ostrom et al., Examining Trial Trends in State Courts: 1976-2002, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 755, 767 fig.6, 773 fig.13 (2004) (measuring trial rates in a sample of states and showing that civil and criminal trial rates declined in all states but at varying rates); Stephen B. Burbank, Vanishing Trials and Summary Judgment in Federal Civil Cases: Drifting Toward Bethlehem or Gomorrah, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 591, 606–17 (2004) (describing trial rates and dispositive motions in U.S. federal courts). ↑

- Herbert M. Kritzer, Disappearing Trials? A Comparative Perspective, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 735, at 745–46, 748–51 (2004) (describing trial rates in England and Canada). ↑

- See Thomas J. Stipanowich, ADR and the “Vanishing Trial”: The Growth and Impact of “Alternative Dispute Resolution”, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 843, 911–12 (2004) (juxtaposing the decline in trial rates with the increase in ADR). ↑

- See Elizabeth Warren, Vanishing Trials: The Bankruptcy Experience, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 913, 930–37 (2004) (attributing declining trial rates in bankruptcy to increasing costs of litigation (the “cost” hypothesis) rather than judges’ workloads). ↑

- See Shari S. Diamond & Jessica Bina, Puzzles About Supply-Side Explanations for Vanishing Trials: A New Look at Fundamentals, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 637, 654–57 (2004) (examining the role of judicial resources in the declining rate of trials); Gillian K. Hadfield, Where Have All the Trials Gone? Settlements, Nontrial Adjudications, and Statistical Artifacts in the Changing Disposition of Federal Civil Cases, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 705, 728–33 (2004) (noting that the period 1970 to 2000 witnessed both declining rates of trial and declining rates of settlement). ↑

- See Judith Resnick, Migrating, Morphing, and Vanishing: The Empirical and Normative Puzzles of Declining Trial Rates in Courts, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 783, 804–11 (2004) (discussing how non-trial adjudication reduces information available to the public on relevant litigation matters). ↑

- See Paul Butler, The Case for Trials: Considering the Intangibles, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 627, 632 (2004) (“[T]he rejection of trials feels like a devaluation in a public good . . . .”). ↑

- But see Lawrence M. Friedman, The Day Before Trials Vanished, 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 689, 694 (2004) (commenting that “[m]aybe there would be regret if the trial vanished altogether, but no tears are shed if the numbers are kept safely low”). ↑

- See, e.g., The Vanishing Trial (FAMM & National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers 2021) (a documentary short examining the trial penalty through the stories of four criminal defendants who must decide whether to accept plea agreements or risk a much harsher sentence at trial). ↑

- Our January 20, 2022 search in Westlaw’s Secondary Sources: Law Reviews & Journals database found 1,419 unique articles between 2002 and 2021, inclusive, and the same search in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library, which has a slightly different set of sources, uncovered a comparable 1,467. ↑

- See, e.g., Sarah Staszak, No Day in Court: Access to Justice and the Politics of Judicial Retrenchment 3 (Oxford Univ. Press 2015) (discussing diminishing access to trials and the negative impact on access to justice); Robert Katzberg, The Vanishing Trial: The Era of Courtroom Performers and the Perils of Its Passing (2020) (discussing Katzberg’s career trying cases for juries and the danger of their diminishing existence). ↑

- See Marc Galanter, A World Without Trials, 2006 J. Disp. Resol. 7 (analyzing whether the marked decline in trials in the U.S. is a cause for alarm or celebration); discussion accompanying infra Section II.A. ↑

- E.g., Owen M. Fiss, Against Settlement, 93 Yale L.J. 1073, 1083–90 (1984) (arguing that presenting settlement and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms as alternatives to judicial adjudication “trivializes the remedial dimensions of a lawsuit” and downplays the social aspect to what may appear to be private disputes). ↑

- See, e.g., Harry T. Edwards, Alternative Dispute Resolution: Panacea or Anathema?, 99 Harv. L. Rev. 668, 671 (1986) (expressing skepticism about a rush to embrace alternative dispute resolution without proper consideration of its place in relation to “existing court procedures” and its impact on public rights and duties). ↑

- See, e.g., Robert H. Mnookin & Lewis Kornhauser, Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: The Case of Divorce, 88 Yale L.J. 950, at 950–51, 968 (1979) (arguing that extant legal rules as well as non-legal factors allow parties to privately resolve disputes without judicial intervention in a process that they term “bargaining in the shadow of the law”); cf. Betsey Stevenson & Justin Wolfers, Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: Divorce Laws and Family Distress, 2006 Q.J. Econ. 267, 275–86 (finding that the passage of unilateral divorce laws impacted not only divorce but also the marital relationship, decreasing domestic violence and suicide and possibly improving decisions to marry). ↑

- E.g., George L. Priest & Benjamin Klein, The Selection of Disputes for Litigation, 13 J. Legal Stud. 1, 13–20 (1984) (asserting that the decision to settle versus litigate is a purely economic one and that potential litigants are rational in deciding whether to sue or settle). ↑

- See, e.g., William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner, Adjudication as a Private Good, 8 J. Legal Stud. 235, at 238–40, 263–67 (1979) (contending that the assumption that the common law tends to produce efficient rules is misplaced). ↑