Open PDF in Browser: Kyriaki “Kiki” Council,* Facing the Music: How the FACE Act Harms, Rather than Helps, the Post-Dobbs Abortion Movement

Introduction

In the wake of numerous violent attacks on abortion clinics in the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. Congress passed the Free Access to Clinic Entrances Act (“FACE Act,” “FACE,” or “the Act”) in 1994.[1] The FACE Act has dual aims: first, to criminally prosecute those who violently obstructed (or threatened to obstruct) access to reproductive health services facilities; and second, to create a private right of civil action for those harmed by such obstruction.

This Article aims to serve as a nearly thirty-year retrospective of the FACE Act, particularly in light of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. While Congress enacted FACE with the seeming intent of protecting abortion clinics and providers, it has become ever more apparent that FACE does little to deter violence against abortion clinics and their workers. Indeed, violent attacks on abortion providers and clinics have rapidly increased since the Dobbs decision.[2] Moreover, battling an existential threat to FACE after the Dobbs ruling, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has, for the first time since FACE’s passage, outwardly adopted the position that FACE is content- and viewpoint-neutral.[3] Thus, the Act may be enforced against those who obstruct (or attempt to obstruct) access to so-called Crisis Pregnancy Centers (“CPCs”), also known as Anti-Abortion Pregnancy Centers (“AAPCs”), or Fake Abortion Clinics (“FACs”).[4] Case research, discussed infra, reveals only three prosecutions under the FACE Act against those who claimed to be pro-abortion prior to the Dobbs decision. However, the same research indicates that such prosecutions have increased since Dobbs. Interestingly, as discussed below in Section I.D, under the Biden Administration, prosecutions of those who obstruct or attempt to obstruct access to CPCs appear to be more swiftly carried out than prosecutions of those who have perpetrated violent attacks against abortion clinics.

As the abortion movement in America as a whole faces grave threats to its existence, now is the time to question which legal tactics are valid or useful to pursue for the protection of existing resources and workers. This Article posits that an abortion movement invested in collective liberation, particularly the liberation of Black and Brown bodies, should move away from utilizing criminal and civil statutes such as the FACE Act.[5] I argue throughout this Article that the FACE Act harms, rather than helps, the post-Dobbs abortion movement because it demands participation in a legal system that is likely unable to reconcile its problematic approaches to race-, as well as to sex- and gender-based laws. The abortion movement cannot square its own abolitionist leanings and desire to liberate all bodies with the current legal system, particularly under a federal legal system that no longer recognizes one’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Rather than trying to conform itself to the contradictions of the current legal system, I argue that the movement should make a radical pivot from previous strategies entrenched in the law, and instead invest in and turn to grassroots and community organizing to protect itself, abortion clinics, providers, and supporters.

In Part I of this Article, I offer the background and history of the FACE Act, including legislative intent, court interpretation of FACE over the years, and how the FACE Act has been used in post-Dobbs America in light of escalating anti-abortion violence. Using feminist and abolitionist frameworks established by scholar and Professor Aya Gruber, Part II of this Article explores and confronts whether use of the FACE Act by pro-abortion proponents can comport with an abortion movement invested in the liberation of all Black and Brown bodies via anti-White-supremacy, pro-Black, and abolitionist values. Part III of the Article briefly explores and discusses one methodology for moving away from criminalization: community mutual aid.

I. Background & History

A. The Impetus for FACE: Violence Against Abortion Clinics and Providers

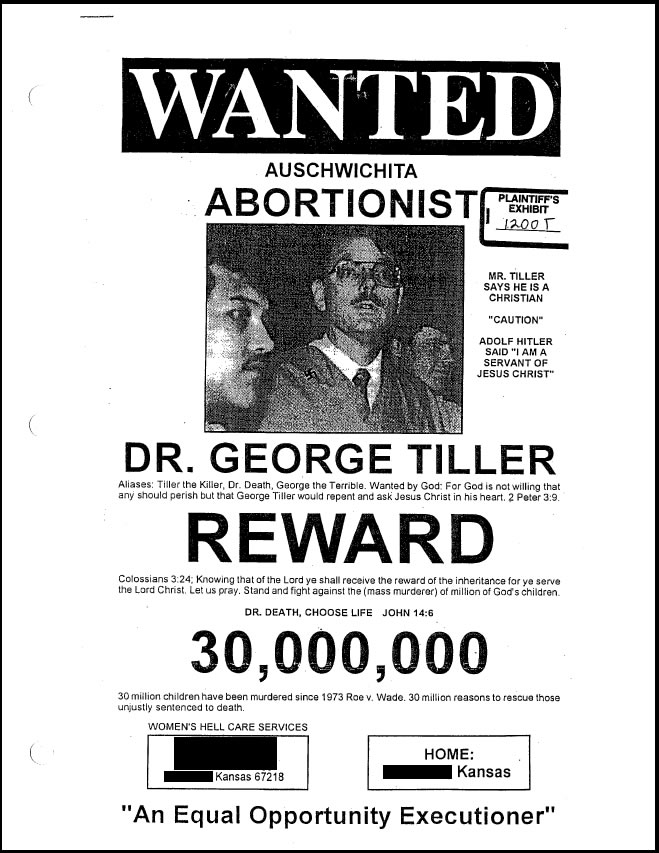

Violent attacks on abortion clinics and providers go hand in hand with the right to choose abortion care. From 1977 until 1993, there were at least nine documented murders, seventeen attempted murders, 406 death threats, 179 incidents of assault or battery, and five kidnappings committed against abortion providers.[6] Abortion providers also faced other forms of harassment and stalking, including use of their photographs and home addresses on “Wanted for Murder” posters.[7]

Figure 1[8]

Figure 1[8]

During the same time period, property crimes committed against abortion clinics include 41 bombings, 175 arsons, 96 attempted bombings or arsons, 692 bomb threats, 1,992 incidents of trespassing, 1,400 incidents of vandalism, and 100 attacks with butyric acid.[9]

Although documented violence against abortion providers and clinics began in the 1970s, anti-abortion extremism and violence escalated throughout the 1990s.[10] For example, the Army of God (a far-right Christian organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center has classified as a domestic terrorist group[11]) claimed responsibility for bombing or setting fire to over a dozen clinics throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[12] The Army of God, along with other anti-abortion activists, also planned and coordinated attacks, picketing, and blockades of abortion clinics in an attempt to dissuade pregnant people from ending their pregnancies and to disable clinics or providers from doing so as well.[13] Such blockade protests often entailed physical invasion of abortion clinics, destruction of the property itself, and exterior vandalism with threatening or gruesome messages.[14] The Army of God Manual offered detailed instructions “on how to build ammonium nitrate bombs and ‘homemade C-4 plastic explosive,’” and suggested “maiming abortion doctors ‘by removing their hands, or at least their thumbs below the second digit.’”[15]

Many articles reflecting on this period in abortion movement history pinpoint two events in particular as the peak of escalating anti-abortion violence in the 1990s.[16] First was the escalation of violent tactics used by anti-abortion activists who invaded and blockaded abortion clinics in the “Spring of Life” protest near Buffalo, New York in April 1992.[17] Second was the murder of Dr. David Gunn, an abortion provider shot and killed by anti-abortion activist Michael Griffin outside of the Pensacola Women’s Medical Services clinic in 1993.[18] Dr. Gunn’s assassination marked the first documented homicide of an abortion provider in the United States.[19]

In direct response to the increasing anti-abortion violence, Senator Ted Kennedy introduced the FACE Act in January 1993.[20] Senator Kennedy chiefly sponsored the bill.[21] During debate on the bill in early May 1994, Congresswoman Louise Slaughter advocated that the legislation aimed to “protect women, their doctors and health clinic staff from systematic, orchestrated violence at reproductive health centers around the country.”[22] She went on to state: “By now we have all heard supporters of this bill repeat the horrible statistics over and over: Bombings, arson, death threats, assaults, kidnappings, clinic ‘invasions’ and murder – all in service of an orchestrated campaign to deny women reproductive choice, at any cost.”[23] Congresswoman Slaughter noted that, in the time that it took to pass the Act, several events in the intervening months

have helped to make the case for this legislation even stronger: The conviction of the Florida assassin who killed Dr. David Gunn; the interrogation of a suspect in another attack on a doctor provided the first look at a national conspiracy of violence; and the Supreme Court approved the use of the [Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations] statute to combat this network of terror.[24]

The Act ultimately passed through both chambers, and then-President Bill Clinton signed the Act into law, which became effective in May 1994.

B. Structure of the FACE Act and Relevant Definitions

The FACE Act is particularly unique in nature because it is a double-intent statute that requires both (1) proof of the intent to interfere with access to reproductive health services; and (2) the intent to intimidate—either through physical obstruction, intentional injury, attempts to injure, or by destruction of property. Under the FACE Act, anyone who

(a)(1) by force or threat of force or by physical obstruction, intentionally injures, intimidates or interferes with or attempts to injure, intimidate or interfere with any person because that person is or has been, or in order to intimidate such person or any other person of any class of persons from, obtaining or providing reproductive health services;

(2) by force or threat of force or by physical obstruction, intentionally injures, intimidates, or interferes with or attempts to injure, intimidate or interfere with any person lawfully exercising or seeking to exercise the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship; or

(3) intentionally damages or destroys the property of a facility, or attempts to do so, because such facility provides reproductive health services, or intentionally damages or destroys a place of worship,

Shall be subject to the penalties provided in subsection (b) and the civil remedies provided in subsection (c) . . . .[25]

Under FACE, the term “facility” includes “a hospital, clinic, physician’s office, or other facility that provides reproductive health services, and includes the building or structure in which the facility is located.”[26] The term “reproductive health services” means “reproductive health services provided in a hospital, clinic, physician’s office, or other facility, and includes medical, surgical, counseling or referral services relating to the human reproductive system, including services relating to pregnancy or the termination of a pregnancy.”[27]

C. Court and Administrative Interpretation of FACE Over the Years: Focus on Constitutionality

At first glance, it would appear that the driving force behind the FACE Act is protection of abortion providers and abortion clinics, particularly given both the violent attacks against abortion providers and clinics that peaked in the 1990s and the legislative history explicitly stating so, as discussed above. However, as discussed in this Section, courts have nearly consistently interpreted FACE to include non-abortion related services despite the fact that very few FACE civil claims or criminal prosecutions have been pursued for those obstructing or opposing non-abortion related services. Indeed, the conclusion that FACE is a content- and viewpoint-neutral statute under the First Amendment seems to have arisen out of necessity to preserve the use of the statute to criminally prosecute and target those violently attacking abortion providers and clinics.

A slight legal paradox arises: in order to use the statute for its intended purpose of protecting abortion clinics and to uphold the constitutionality of the statute, courts have been forced to take the contrasting positions that FACE applies equally to anyone attempting to intimidate or obstruct a patient from accessing any reproductive health services—despite the fact that increasing violence against those seeking or providing anti-abortion services was not the impetus for the statute itself.[28] This Section closes with a review of cases filed against pro-abortion proponents that shows that the level of intimidation, violence, or obstruction faced by anti-abortion proponents is greatly unequal, with the vast majority of violent threats and actions being perpetuated against pro-abortion providers and supporters.

Despite the reality of how violence in the real world plays out, along with the violent reality that led to FACE itself, these cases state that FACE is a content- and viewpoint-neutral statute[29] that applies equally to protect those seeking to access facilities and individuals that oppose abortion. And, more recently, the DOJ itself has publicly taken the position that the FACE Act “is not about abortions.”[30] Instead, the DOJ posits that the statute “protects all patients, providers, and facilities that provide reproductive health services, including pro-life pregnancy counseling services and any other pregnancy support facility providing reproductive health care.”[31] Even so, as detailed below, there has been at least some degree of confusion among courts about the extent to which religious counseling, particularly so-called street or sidewalk counseling, is protected by the FACE Act.

1. United States v. Brock: Finding FACE Content- & Viewpoint-Neutral

Anti-abortion proponents charged under the Act began challenging the constitutionality of the FACE Act under the First Amendment almost immediately after its passage.[32] In United States v. Brock, defendants who were charged with violating section 3 of FACE challenged the law, claiming it was constitutionally infirm because it was a “content-based or viewpoint-based regulation of expressive activity” and because it was vague and overbroad.[33] The defendants lodged the argument that FACE’s obstruction provisions discriminated against them based on viewpoint because FACE targets messages on “one side” of the reproductive health services debate.[34] The district court disagreed, noting that the language of the statute did not support such a conclusion, and that “on its face the statute applies equally to activities directed at the patients and staff of abortion clinics and the patients and staff of centers that counsel women against abortion and in favor of its alternatives.”[35] The court additionally noted that no evidence had been presented to indicate that the DOJ would fail to apply the statute to control violent and obstructive pro-choice protests.[36]

Ultimately, the Brock court found that the statute would apply equally to anti- and pro-abortion proponents because the true government interest driving the FACE Act is access to reproductive health services, as opposed to access to reproductive health service facilities: “Absent the necessary intent to deprive someone from obtaining or providing services, FACE simply does not apply.”[37]

2. Norton v. Ashcroft: Anti-abortion Street Counseling Is Covered by FACE

In Norton v. Ashcroft, several anti-abortion protestors and religious street counselors sued the Michigan Attorney General, the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Michigan, and other state and federal officials in their official capacities, challenging the constitutionality of the Act.[38] Plaintiffs had been warned by state officials as well as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) that their counseling activities, which at times included obstructing the entrance to an abortion clinic, could lead to prosecution under FACE.[39] Citing several previous cases, the Sixth Circuit upheld the lower court’s ruling that FACE is both content- and viewpoint-neutral, noting that “the Act prohibits interference not only with abortion-related services,” but that it also prohibited “interference with counseling regarding abortion alternatives . . . regardless of ideology or message.”[40] The court did not analyze whether street or sidewalk counseling would fall under the Act’s definition of “facility.”

In supporting this rationale, the court emphasized the fact that the Act had already been applied to at least one pro-abortion protester who threatened workers at an anti-abortion facility.[41] Moreover, the fact that more anti-abortion protestors had been prosecuted under FACE than pro-abortion protesters did not matter as there is no disparate-impact theory under the First Amendment.[42] As with the Brock court, the Norton court’s analysis hinged on the neutrality of the statute, coupled with the defendants’ apparent efforts to obstruct a patient’s ability to access reproductive health services.

3. Raney v. Aware Woman Center for Choice, Inc.: Anti-abortion Street Counseling Is NOT Covered by FACE

Despite repeated findings by other courts that anti-abortion counseling services fall under the purview of the FACE Act, the Eleventh Circuit in Raney v. Aware Woman Center for Choice, Inc. reoriented the analysis by focusing on what Congress intended by requiring that a person bringing a FACE action be seeking or providing reproductive health services in a “facility,”[43] thus creating a circuit split. According to the Raney court, by requiring that the person bringing a FACE action be seeking or providing reproductive services in a “facility,” “Congress recognized the difference between trained professionals who work in credentialed facilities and unregulated volunteer counselors who are not attached to recognized providers of reproductive healthcare.”[44] Accordingly, because the plaintiff, Raney, was standing on a sidewalk outside of the abortion clinic, he could not claim that he was in a facility or that he was offering the type of reproductive health services to which the FACE Act protects access.[45]

4. Cases Where Pro-abortion Proponents Were Defendants

Case research indicates that before Dobbs, only three pro-abortion proponents had been sued or prosecuted under FACE. As indicated above, the court in Norton v. Ashcroft alluded to the fact that a pro-choice activist was prosecuted for violating FACE in United States v. Mathison.[46] It appears the Mathison matter marked the first time FACE was used in a case involving a facility that did not provide abortions. In that case, the defendant pleaded guilty to drunkenly calling and threatening to shoot anti-abortion proponents who worked at the First Way Center, a CPC located in East Wenatchee, Washington.[47] Mathison apparently admitted to considering the threatening call he made to the CPC to be a form of terrorism and that he intended to “instill fear in the pro-life movement similar to what the pro-choice people have to deal with.”[48]

Approximately three years later, in Greenhut v. Hand, an anti-abortion worker at a CPC sued a pro-abortion woman who made four telephone calls to the worker’s personal residence—the worker’s phone number was made publicly available through the CPC.[49] Though the plaintiff was not home at the time of the calls, her answering machine recorded the threatening messages left by the defendant, including one that stated, “Hello Janet. Get your murderers away from abortion clinics now or you will be killed.”[50] Another stated, “Janet, get your pro-lifers away from our clinics or we will kill you.”[51] Despite the previous prosecution against Mathison in 1995, the district court stated that “for the first time, FACE” was being invoked to penalize threats made against a pro-life volunteer.[52] The defendant attempted to fight the civil suit by claiming that the plaintiff did not provide “reproductive health services” and that the defendant did not act with the requisite intent.[53]

Citing previous cases holding that FACE applies to facilities offering pregnant women counseling about alternatives to abortion, the Greenhut court rejected the defendant’s first argument that the statute was not intended to cover services provided by volunteers untrained in the field of counseling or reproductive care.[54] To the Greenhut court, it was sufficient that each volunteer, though not a trained social worker or nurse, was provided with a Resource Guide so that the volunteer could provide referrals to adoption or foster care agencies, medical facilities, day care providers, maternity homes, and prenatal classes.[55] Deviating from the reasoning in the Raney case, the Greenhut court found that “nothing in the [FACE] statute indicate[d] that it cover[ed] only trained providers of reproductive services such as doctors, nurses, or social workers.”[56] The court additionally noted that FACE had been construed to prohibit threats or violence against abortion clinic escorts and maintenance workers at abortion clinics because they were an integral part of a business in which abortions were performed and pregnant people were counseled.[57]

Like the Mathison defendant, the Greenhut defendant claimed to be drunk when making the threatening calls.[58] Accordingly, the defendant argued that she could not have formed the requisite intent to impede, interfere with, or intimidate the plaintiff from providing reproductive health services—she did not know the plaintiff, nor did she intend to impede the plaintiff, but was instead referring to recent incidents by violent anti-abortion extremists.[59] The court remained unpersuaded: first because it found it inconsequential that the defendant intended to express outrage at recent incidents of violence rather than to prevent the CPC worker from continuing her work, and second because the record clearly showed that the defendant called the plaintiff due to her involvement with the CPC specifically.[60]

Finally, in Lotierzo v. Woman’s World Medical Center, Inc., plaintiff-appellants (several volunteers who worked at a CPC located across the street from an abortion clinic) sued the defendant-appellees (escorts, employees, and patients of an abortion clinic) under FACE, seeking to enjoin the defendant-appellees from interfering with the plaintiff-appellants’ ability to provide anti-abortion counseling services on the street and sidewalk outside of the abortion clinic.[61] The district court granted the defendant-appellees’ motion to dismiss, concluding that the plaintiff-appellants had failed to properly allege that the defendant-appellees had actually interfered with the plaintiff-appellants’ ability to provide counseling services.[62] The CPC plaintiff-appellants appealed.

The Eleventh Circuit concluded that the plaintiff-appellants failed to state a FACE Act violation for two reasons.[63] First, the plaintiff-appellants failed to allege that the defendant-appellees’ actions were taken because the plaintiff-appellants were providing reproductive health services at the CPC.[64] Specifically, the court noted that FACE protects “individuals who provide reproductive health services in a facility.”[65] The plaintiff-appellants’ allegations arose due to referral services provided on the street or sidewalk outside of the abortion clinic rather than within the facility itself.[66] Second, the plaintiff-appellants failed to allege that the defendant-appellees’ actions were taken in order to intimidate a person from obtaining or providing reproductive health services at the CPC.[67] Rather, the plaintiff-appellants were merely concerned with their ability to provide referral counseling outside of the CPC and on the sidewalks and street in front of the abortion clinic.[68] Because there was no allegation that the defendant-appellees’ actions prevented any individual from seeking or providing reproductive health services at the CPC, the court affirmed the district court’s conclusion that the amended complaint failed to state a claim under the FACE Act.[69]

However, the court noted that its affirmation of the lower court’s order granting the motion to dismiss did not apply to one plaintiff-appellant’s claim against a defendant-appellee, which alleged that the defendant-appellee visited another CPC facility and threatened the plaintiff-appellant.[70] The plaintiff-appellant alleged both that he provided reproductive health services at the facility and that when the defendant-appellee visited the CPC, she approached another volunteer and threatened to kill the plaintiff-appellant.[71] Thus, the district court erred in dismissing that specific claim.

The reality of the disparities of violence between the pro-abortion movement and the anti-abortion movement, as well as the legislative history of the Act itself, begs the question of why pro-abortion proponents failed to argue that FACE is not a content- or viewpoint-neutral statute from the outset.[72] Perhaps the perceived risk of making such an argument nearly thirty years ago, in light of what was almost certain to be a much higher abortion stigma in the courts, was too great. And, unfortunately, it is not within the purview of this Article to provide a robust analysis of whether FACE might have survived the heightened scrutiny applied to content- and viewpoint-based restrictions on speech. Regardless of such an analysis, well-established precedent exists across U.S. circuit courts that FACE is a content- and viewpoint-neutral statute despite its violent and frightening anti-abortion origins.[73] My analysis now turns to how FACE has been applied in a post-Dobbs America, where violence against abortion clinics and providers is again rapidly rising, but where FACE, for the first time in its statutory history, appears to be more swiftly used against pro-abortion protestors than anti-abortion protestors.

D. FACE in Post-Dobbs America

Discussing the FACE Act in a post-Dobbs America within the appropriate context is critical. In the Dobbs decision, the Supreme Court determined not only that severe abortion restrictions in the state of Mississippi were constitutionally valid but also that the entire underlying substantive due process analysis granting Americans the federal right to choose to access a pre-viability abortion was invalid and must be overturned.[74] The Supreme Court thus abandoned nearly fifty years of super-precedent and returned the question of abortion legality or illegality to the states. This directly resulted in both legal and healthcare chaos across the United States as the Supreme Court, for the first time, had revoked a fundamental right that it had previously established.[75] Both the leak of the Dobbs decision in May 2022[76] and its formal announcement in June 2022 sparked massive protests across the United States.[77]

Since returning the issue of abortion legality back to the states, as of the writing of this Article, abortion is completely banned in fourteen states.[78] An additional seven states ban abortion at gestational age limits that would have been unconstitutional if Roe v. Wade remained in effect today.[79] In five states, abortion bans are either currently enjoined or being litigated.[80]

In framing the remainder of this Article, it is particularly important to note that abortion in America occupies an entirely different political place now than it did in the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and throughout the first twenty years of the twenty-first century.[81] Abortion is a human right that many on the left took for granted and was suddenly stolen away overnight. The swift deterioration of the constitutional right to seek an abortion invigorated the growing and particularly violent right-wing faction of our political spectrum, which has been vindicated in its decades-long battle to eliminate the constitutional right to choose. Despite this, for the first time in American history, most citizens support the right to choose an abortion.[82] The majority of Americans also disagree with the Dobbs decision.[83]

Thus, within this context, we can understand both anti-abortion and pro-abortion activism, civil disobedience, and vandalism that arose after May 2022.[84] In the wake of the Dobbs decision leak in May 2022, an anonymous group of individuals calling itself “Jane’s Revenge” posted an online manifesto in the form of a blog that encouraged activists to target CPCs.[85] Following the blog post, there was a reported increase in pro-abortion vandalism, protesting, and sometimes violence against CPCs across the country. As discussed by Endora, a pro-abortion rights group that seeks to centralize information about hostile, anti-abortion actors in the United States, media coverage of the pro-abortion vandalism and protests greatly outweighed coverage of increased violence against abortion clinics and providers despite the fact that pro-abortion actions “are still drastically dwarfed by anti-abortion disruptions.”[86]

According to Endora’s research, since May 2022, there have been 144 incidents that genuinely qualify as pro-abortion disruptions that occurred either at religious institutions or CPCs.[87] Of those 144 incidents, 118 were vandalism, four were peaceful church invasion protests that did not obstruct or restrict entrance to the space, two were threatening public statements, and only one was a larger protest that targeted a CPC and required police involvement.[88]

In stark contrast, since May 2022, the National Abortion Federation (“NAF”) reported 1,007 “serious disruptions” against abortion clinics and providers.[89] This figure does not include NAF’s reports of less serious disruptions against abortion clinics and providers, including 2,413 receipts of hate mail and calls, 19,765 reported incidents of online harassment, 2,100 incidents of obstruction, and 112,068 reports of picketing.[90] Of special import with these statistics is the fact that forty-two independent abortion clinics closed due to abortion restrictions as of December 2022.[91] Thus, the magnitude of harm experienced by the remaining abortion clinics and providers is even greater. Endora also concludes that it is fair to say that anti-abortion disruption would have been significantly higher if any number of the forty-two abortion clinics that closed had remained operational and had been able to report their numbers for the year 2022.[92]

Per Endora’s reporting, attacks by anti-abortion activists exceeded similarly reported attacks by pro-abortion activists by several degrees: arson (7:4), attempted arson (5:1), and vandalism (118:101).[93] Endora notes that vandalism attacks on abortion facilities are inaccurately reported because they are so common.[94] And, in all other categories of serious incidents, anti-abortion attacks were experienced at far higher rates: assault (40:5), bioterrorism threats (4:0), blockades (6:0), bomb threats (10:2), burglary (43:0), serious threats of violence (218:2), invasions (20:4), stalking (92:0), suspicious packages (73:0), and trespassing (395:0).[95]

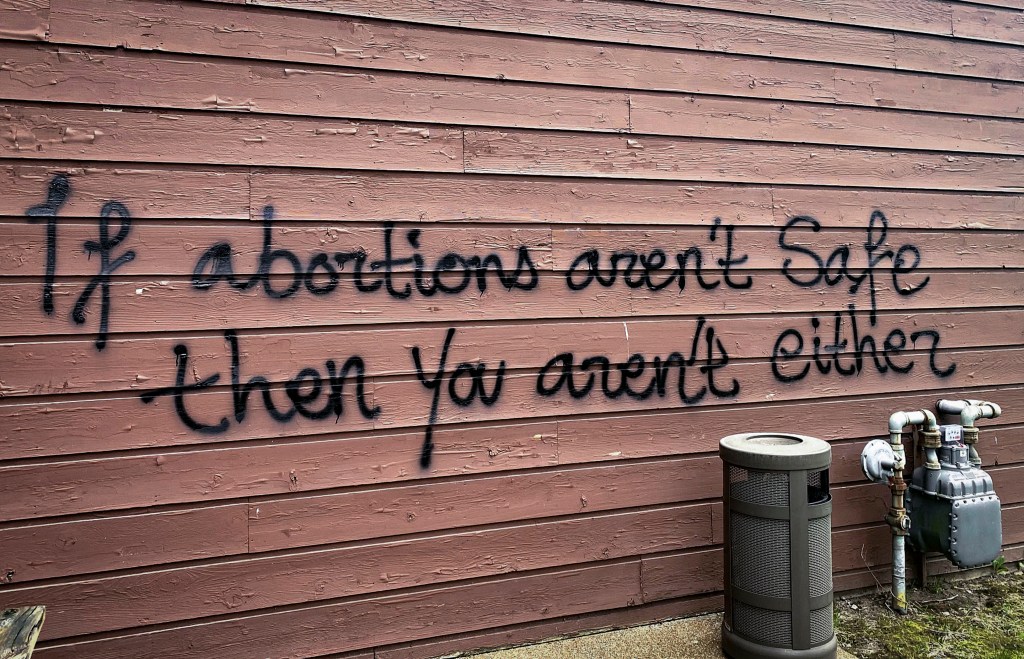

Despite the uptick in violence against both CPCs and abortion clinics (particularly against abortion clinics and providers) since May 2022, the DOJ has reported only ten FACE Act criminal indictments, consent decrees, or guilty pleas.[96] One of those indictments includes an attack against a CPC filed in the United States District Court Middle District of Florida–Tampa Division.[97] The Florida defendants allegedly targeted and vandalized a CPC in Hollywood, Florida with the message, “If abortions aren’t safe then neither [sic] are you.” Approximately one month later, the defendants allegedly traveled to Winter Haven, Florida and vandalized a facility by spray-painting “YOUR TIME IS UP!!,” “WE’RE COMING for U,” and “We are everywhere” on the facility.[98] Approximately one week later, the defendants traveled to Hialeah, Florida and allegedly spray-painted, “If abortions aren’t safe the [sic] neither are you” on another CPC.[99]

Figure 2[100]

Figure 2[100]

Notably, only two recent incidents of vandalism implicating the FACE Act are reported on the DOJ’s webpage that reports recent cases on violence against reproductive healthcare providers.[101] In 2021, a defendant pled guilty to damaging a Newark, Delaware abortion clinic by firebombing the facility and vandalizing it with spray paint.[102] That defendant spray-painted the White supremacist/Christian nationalist phrase “Deus Vult”[103] in red letters on the front porch of the building and then threw a Molotov Cocktail through the front window of the facility.[104] The explosion reportedly damaged the front window and the porch of the building but self-extinguished after approximately one minute.[105] In 2016, the DOJ charged two defendants with FACE Act violations for vandalizing a Baltimore, Maryland area abortion clinic on two separate occasions.[106] According to one defendant’s plea agreement, the defendants spray painted the words “Kill,” and “Dead Baby Fuck you” on one clinic before returning to the clinic the next day where they spray-painted the words “Kill Dead Baby,” “Baby Killer,” and “Kill Baby Here” on the clinic’s walls with arrows pointing to the clinic doors.[107]

Deeper examination of the DOJ’s reports on recent FACE Act violations reveals an even more disturbing trend: of the most recently reported cases against those perpetuating anti-abortion violence, none are from the period between May 2022 and May 2023.[108] Indeed, the only recently reported FACE Act case from that critical time period is the criminal case against the pro-abortion activists who allegedly targeted Florida CPCs, discussed above. If anything, the DOJ’s own reports of recent cases reveal a relative lag time in reported incidents of violence against pro-abortion clinics and eventual prosecution. Several of the 2022 indictments are related to incidents that took place in 2021 and 2020.[109] One 2019 indictment relates back to a 2015 shooting at a Planned Parenthood facility in Colorado Springs, Colorado, where the defendant allegedly traveled to the abortion clinic and shot at several civilians, killing two and injuring three others.[110] As of the time of publication, that particular defendant has been in custody and awaiting trial due to competency issues since November 2015.[111] It is unclear why it took the DOJ so long to indict the Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood shooter, especially given that the issue of competency has been apparent since the beginning of the matter.

How is it that it took the DOJ approximately four years to indict an incarcerated defendant who had traveled to and killed individuals at an abortion clinic under the FACE Act but mere months to indict several defendants who allegedly coordinated together to vandalize CPCs in the wake of the Dobbs decision, which stripped away long held civil rights? And, more importantly, given the reported uptick in anti-abortion violence against clinics and providers, why has the DOJ failed to indict anti-abortion proponents at a similar rate? What practical purpose does the FACE Act really serve in its attempts to protect abortion clinics and providers? I attempt to analyze and answer these questions in Part II below.

II. Facing the Music: Do We Really Need the FACE Act At All?

Since the inception of the FACE Act, legal scholars have analyzed both state and federal government efforts to protect access to abortion clinics. Analysts point to certain holes in the FACE Act, including how to protect abortion providers who are often victims of stalking and harassment outside of abortion clinics.[112] Scholars propose closing these gaps using hate crime legislation as a unique tool to address the growing national problem of domestic terrorism in the form of anti-abortion extremist groups and encourage the use of state crime legislation for sentence enhancement.[113] While many law review articles analyze the constitutionality of the FACE Act[114] and point to its inability to thoroughly protect both abortion clinics and providers, none of the scholarship confronts an important baseline question: what practical purpose does the FACE Act really serve in its attempt to protect abortion clinics and providers? Or, in other words, since the FACE Act clearly does little to deter anti-abortion extremist violence[115] and now is being used against pro-abortion proponents, do we really need the FACE Act at all, especially given that the constitutional right to access abortion no longer exists? Additionally, does the FACE Act have a proper place in an abortion movement that is invested in liberating all bodies, but particularly Black and Brown bodies?

A. Can the Goals of Reproductive Justice Comport with Criminalization? (No.)

SisterSong, a collective of women of color fighting for reproductive justice, defines “reproductive justice” as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”[116] The term “reproductive justice” itself originated in 1994[117]—the same year as the passage of the FACE Act. A group of Black women who gathered in Chicago recognized that the current women’s rights movement, which had until that point been led by and represented middle-class and wealthy White women, “could not defend the needs of women of color and other marginalized women and trans* people.”[118] Accordingly, the women named themselves Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice and launched the reproductive justice movement.[119]

An increasing number of pro-abortion organizations, coalitions, and individuals within the reproductive justice movement envision a world where “there is no place for white supremacy in any of its manifestations.”[120] These organizations, coalitions, and individuals self-identify as “abolitionists,” stating that they “honor people behind the wall, held in jails, prisons, and detention centers, as well as formerly incarcerated people.”[121] Criminalization of either anti-abortion or pro-abortion proponents is directly at odds with a desire to move away from a criminal system that over-incarcerates Black, Brown, and impoverished people.

While the FACE Act is certainly at odds with an abolitionist approach to reproductive justice, it is also directly at odds with another recent focus throughout the modern abortion movement: centering abortion patients above all others within the “system of care” provision.[122] Statistics show that the vast majority of those seeking abortions in the United States are of lower socioeconomic status (i.e., 49 percent are at or below the poverty level, and a further 26 percent of abortion seekers are two times below the poverty level), Black or Brown, and are likely already a parent.[123] In post-Dobbs America, nearly all abortion patients are having to travel longer distances to obtain care in so-called safe-haven states where abortion remains legal in some form.[124]

Prosecuting a FACE Act claim on a patient’s behalf necessitates involvement with both local law enforcement and the FBI.[125] One could easily speculate that the reason why FACE Act prosecutions are difficult to carry out is a lack of patient cooperation (which is understandable, given abortion-patient demographics and forced travel from states banning abortion care) coupled with obstruction by police, who are well-documented in their own hostilities toward the abortion movement.[126]

The realities of what would lead to a viable FACE Act claim can be conveniently ignored in most legal analyses. It is all too easy to simply recommend that someone call the police in the face of extremist violence, thereby obscuring the trauma faced by abortion providers, clinics, and patients and their own lived realities. What necessitates a call to the police—who again are likely to be unsympathetic to a pro-abortion proponent’s plight—might include physical violence and picketing outside of a clinic, screamed slurs and threats, physical invasion and blockading of a clinic where one is trying to obtain care (and in a post-Dobbs world, likely on a compressed timeline), or an actual attack, such as a firebombing or planned mass shooting or assassination of an abortion provider. Why would a Black or Brown person, who traveled several hundred miles from out of state to obtain abortion care, cooperate with police in the face of such terrifying violence?

Another ignored reality is that of the existence of CPCs and that, based on the so-called “reproductive healthcare services” they actually provide, they do not belong under the definition of reproductive healthcare services and therefore do not belong under the purview of FACE.[127] Such facilities are well-documented as deceptive and misleading religious organizations whose sole purpose is to disabuse women and pregnant people of the very idea of seeking an abortion and often birth control or contraceptives as well.[128] Indeed, several reproductive rights organizations have conducted studies showing that a CPC will pose as abortion clinics in a given community to drive pregnant individuals seeking abortions away from such care—thus sometimes delaying that individual’s ability to seek an abortion depending on where they are located and what the local gestational age limits might be.[129] At least two states have recently passed laws making it a deceptive trade practice for CPCs to advertise services, such as abortion care, when they, in fact, do not provide anything of the sort. Importantly, as noted in a few of the cases supra, CPCs are often volunteer-run and do not employ licensed personnel who are equipped to offer medical opinions on pregnancy or other reproductive health matters. The counseling offered tends to almost always be deeply religious, and again, such counseling is not offered by well-equipped, trained, or licensed individuals. So why do they continue to fall under the purview of the FACE Act?

The seemingly noble impetus behind the FACE Act—to protect access to abortion clinics—coupled with the realities of carrying out its prosecutions, serves as a magnifying glass on the American criminal system and all of its inherent contradictions. On one end of the spectrum is the righteous urge to protect and prevent violence, while on the other end is a complete refusal to center those who are victims of said violence or, perhaps more importantly, prevent or deter similar violence from occurring in the future. FACE demonstrates what so many see but are too afraid to say outright: that the legal system is seriously broken—as demonstrated by the loss of Roe itself, let alone the use and misuse of FACE—and that we must move beyond the law to truly protect not only abortion providers and clinics, but also, most importantly, those who are seeking abortions.

B. Incorporating an Abolitionist Framework in the Abortion Movement and Reproductive Justice Movement

Abortion and its legal status hinge on state involvement in a citizen’s sex life, as few would disagree that pregnancy, wanted or not, is a direct result of the act of sex. While, for now, the vast majority of laws criminalizing abortion do not target the pregnant individual, this Article approaches abortion laws, including the criminalized component of the FACE Act, with the view that, like sex-based crimes, any law related to abortion is inherently rooted in sex and gendered expectations in an inherently hierarchical and patriarchal legal system.

There is no shortage of legal scholarship analyzing the propriety of sex-based crimes, including rape, sexual assault, prostitution, lewd behavior, and indecent exposure, among other crimes. Scholars like Professor Aya Gruber have repeatedly pointed out that feminists often advocate for a host of reforms to strengthen state power to punish gender-based crimes.[130] In the context of rape, Professor Gruber urges feminists to confront the use of criminal law as the primary vehicle to address sexualized violence by carefully weighing the purported benefits of reform against “the considerable philosophical and practical costs of criminalization strategies before making further investments of time, resources, and intellect in rape reform.”[131] Using Professor Gruber’s framework, I argue below that there is a serious conflict and tension between the modern abortion and reproductive justice movement’s desire for liberation of all bodies, particularly of Black and Brown bodies, and its simultaneous urge to proliferate and utilize pro-prosecution and pro-criminalization approaches to protect abortion clinics, abortion providers, and, ultimately, abortion patients.

As discussed above in Section I.C, since its inception, the FACE Act has faced serious challenges to its constitutionality under the First Amendment. In order to uphold the statute and attempt to protect abortion providers and clinics as intended, courts have been forced to find that the statute is content- and viewpoint-neutral despite its clear origins to the contrary. As noted by several legal scholars, such an argument stretches the bounds of the content- and viewpoint-neutral First Amendment analyses and somehow still fails to adequately protect abortion clinics and providers. In urging further criminalization and enhanced sentencing, feminist scholars—those who clearly believe in one’s right to self-determination, bodily autonomy, and one’s ability to choose to perform or have an abortion themselves—seemingly urge policies that will further limit the constitutional rights of defendants and confound the ultimate liberation of every body.[132]

Professor Gruber argues, and I agree, that the criminal system is culturally and structurally inconsistent with feminist values.[133] As noted by Professor Gruber and feminist scholar bell hooks, “the criminal law and its culture” are the “very embodiment of ‘the Western philosophical notion of hierarchical rule and coercive authority,’ which serves as the ‘foundation’ of male domination of women.”[134] Gruber notes that there are oppositional power forces natural to the criminal justice system, such as a “bad criminal” and a “good victim.”[135] These oppositional power forces become readily apparent through the lens of the FACE Act. Because the FACE Act was so clearly intended to protect abortion clinics and providers (i.e., the “good victims”) from violent anti-abortion protestors (i.e., the “bad criminals”), it feels extremely uncomfortable to confront the fact that those roles may be reversed, and either pro- or anti-abortion activists could be criminally charged under the Act. It seems incongruent that the bucket of “bad criminals” under the FACE Act could include both violent and destructive right-wing White supremacists and Christian nationalists as well as left-wing activists using graffiti to respond to a long held human and civil right suddenly being stripped away by the nation’s highest court.

There is a sort of twisted irony in relying on the government, particularly the federal government, to protect any sort of access to abortion at the present moment, given the fact that there is no longer a constitutionally recognized right to seek an abortion. One could argue that prosecutorial discretion should endeavor to protect pro-abortion activists from fearing that the FACE Act will be used maliciously against them, particularly under a friendly presidential administration. However, as noted by Professor Gruber, “prosecutorial discretion combined with state actors’ drive to win leads law enforcers to abandon ‘loser’ cases,” and thus focus their time and energy necessarily on those cases that will win.[136] Since the driving force of prosecutors is to “win” rather than to enforce or carry out justice, the prosecutor will almost always certainly choose or opt for the winning case rather than the “right” case.[137] Such a drive is clearly demonstrated by the most recent FACE Act prosecutions that focus on the very few so-called “violent” incidents (i.e., property damage) against CPCs rather than focusing on the immense and demonstrably violent incidents against abortion providers and clinics.

Alleged prosecutorial neutrality[138] in criminal FACE Act prosecution reveals the baseline issue in using such a statute to support abortion access in post-Dobbs America: how can we trust, in an especially politically polarized nation, that following presidential administrations will continue to use FACE to protect abortion clinics at all? The legal groundwork to use FACE against pro-abortion proponents has been well-laid. That, coupled with anti-abortion sentiment among the police, does not bode well for future FACE Act prosecutions under a less abortion-friendly presidential administration.

How can the federal government hold two inconsistent positions—that there is no constitutional, federal right to choose abortion (let alone to access abortion), but that there simultaneously exists a federal right to not be intimidated away or obstructed from accessing reproductive health services, specifically abortion care? There too remains the legal tension between the existence of FACE in a post-Dobbs America. Perhaps FACE served as an important protective mechanism for clinics when abortion was constitutionally valid, but the stark reality is that millions of Americans of reproductive age are now unable to access reproductive health services, namely abortion, in approximately half of the United States. Moreover, there is the reality that both the right to abortion and access to abortion will continue to diminish over time.

III. Beyond the Law: Alternatives to Criminalization

Rather than rely on the law, particularly federal law that has already failed to protect millions of Americans in their ability to choose an abortion, the abortion movement should instead shift focus and resources away from legal remedies and towards community and grassroots resources to protect abortion clinics, abortion providers, and abortion seekers. Doing so requires a unified commitment to move away from, and beyond, the law. Such a concept is admittedly difficult to confront as an attorney, particularly within the context of a law review article. However, as discussed at length above, the law, especially the federal law, is no longer a reliable source of protection for this subsection of the population and arguably never was, as FACE has done little, if anything, to deter violence against clinics and providers or to make abortion clinics, providers, or seekers feel safer. This is also an admittedly difficult concept to confront because the modern abortion movement is nowhere near unified in any of its efforts, let alone in its approach to addressing ongoing violence against pro-abortion proponents. Despite the realities of FACE, including its shortcomings, contradictions, and potential future dangers, major pro-abortion proponents like NAF will likely continue to support FACE and state interventions on anti-abortion violence.

In order to move beyond the law and criminalization, community organizers advocate first for community care in the form of mutual aid.[139] Mutual aid has been defined as “cooperation for the sake of the common good” and focuses on localities coming together to meet each other’s needs, “recognizing that as humans, our survival is dependent on each other.”[140] As described by organizer Dean Spade, “the framework of mutual aid is significant in the context of social movements resisting capitalist and colonial domination, in which wealth and resources are extracted and concentrated and most people can survive only by participating in various extractive relationships.”[141] Rather than continuing to perpetuate harm in such a system, mutual aid instead urges “providing for one another through coordinated collective care” which can be both “radical and generative.”[142]

Within the context of abortion care, community mutual aid would first entail developing neighborhood buy-in and support for abortion clinics—mutual aid must start from the bottom and work its way upwards. Developing support for abortion clinics would require not only demonstrating what a clinic might offer to the community itself but also educating the community about the importance of abortion and how it helps the community overall, not just those traveling to the community for abortion care. Those included would-be individuals who live in the same neighborhoods as clinics, local businesses, as well as groups frequently targeted for anti-abortion violence (i.e., providers, other clinic workers, clinic escorts, counter protestors, and, if willing, those in the community who have sought abortions themselves—whether at that clinic or another).

The next step would be to train and develop this supportive community into a version of a neighborhood watch system. Such a neighborhood watch would be trained to collect and share information on anti-abortion proponents who enter the neighborhood. Presently, there are very few resources for those who provide or support abortion care in a given community to communicate with each other in a secure way about what they might be seeing from anti-abortion proponents locally, on a state level, and nationally. Coordinating and bolstering the ability of providers or supporters of abortions to communicate would be essential to the successful development of an abortion-forward community.

While organizing a community around a clinic necessitates some degree of pro-abortion buy-in by the neighborhood, which may be admittedly difficult depending on where the abortion clinic is located (for example, if the clinic is located in a state or county that has not banned abortion access, but is hostile to such access politically), the ultimate goal is to make those who might feel the propensity to inflict violence on the community to feel both surveilled by the community and unwelcome.[143] It must be noted here that many CPCs situate themselves in close proximity to abortion clinics. It is therefore critical that pro-abortion community resources become more visible in spaces and neighborhoods around abortion clinics as well as a part of this effort. Essentially, the idea is to drive animus against abortions out of a given area as thoroughly as possible. Anti-abortion proponents, whether extremist or not, have always seemingly had the upper hand in such community organizing, and pro-abortion proponents are long overdue in their answer to such organizing.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of community organizing within the context of preventing anti-abortion violence is confronting the reality of the violence itself. As is now repeatedly discussed, little seems to deter anti-abortion extremists from perpetuating violence (physical or property) against clinics, providers, and seekers. While the hope would be that bolstered community support, surveillance, communications, and resources around abortion would mitigate or deter at least some community violence, there is a plain reality that anti-abortion sentiment will continue to rise as American politics continues along its ever-polarizing trajectory. This of course begs the question of whether mutual aid contemplates violence itself, and if so, what kind(s) of violence? Must there always be the presence of armed individuals around abortion clinics in order to protect the clinics, its providers, its patients, and its supporters or to deter violence? Should a movement that we are presuming must be invested in the absolute liberation of all bodies be invested in arming its members? Without the benefit of a completely separate and very complicated analysis, suffice it to say, I should think not.

I believe that confronting such questions must be left to individual communities while also acknowledging that this is the most difficult aspect of confronting a reality beyond the law. There simply is not, at present, a good community alternative when it comes to actual violence. Such an unfortunate fact demonstrates why it is so difficult for many of us to imagine a system beyond the law. Even if criminalization does little in reality to deter future violence and ultimately harms Black and Brown bodies disproportionately, at least we can retain some hope that so-called justice might be met by those who choose to target abortion clinics, providers, and seekers with violence.

Conclusion

Despite the difficult reality of moving beyond the law, it is critical now, more than ever, for pro-abortion proponents to confront the realities of the failures of the current legal system, to begin organizing their communities, and to begin to dream up alternatives to what exists now. Further criminalization under FACE or any other federal statute, similarly enhanced criminal sentences, and increased surveillance by our police state will not ultimately work to our favor, particularly when the next politically polarized anti-abortion president takes office (it is only a matter of time). The transformative effect of simple community organizing around abortion clinics to create abortion-forward neighborhoods is yet to be seen because it does not yet exist. We must think expansively and creatively to not only protect those in our communities who provide and support abortion but to continue to preserve the precious right to seek abortion itself.

*Legal Counsel for Pro Bono Initiatives at The Lawyering Project. Kiki strives to secure every human’s legal and social rights to autonomy over their choices for their bodies, especially the right to choose an abortion. She received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of Chicago and her Juris Doctor from the University of Colorado. Kiki has worked and volunteered in the abortion movement for over a decade: from abortion clinic escorting, to abortion fund board service, to representing young people in Colorado who seek abortions without forced parental involvement. Kiki would like to thank her summer intern Nargis Aslami, as well as her family, friends, colleagues (especially those throughout the abortion movement who served as sounding boards for this Article), and the editorial board of the University of Colorado Law Review for their tireless support in developing this Article as Kiki ironically battled several illnesses related to her pregnancy. This article is dedicated both to her son, Landon, the child she chose, as well as to all the young people she has represented in judicial bypass petitions. The future is yours.

- 18 U.S.C. § 248. ↑

- See Comparative Reporting on Abortion Related Incidents 2023, at 4–5, Endora, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WCAJS1GzbUzb5qzouBOdMQRHL0oe4B_G/view [https://perma.cc/W775-B6SD]. ↑

- Compare Protecting Patients and Health Care Providers, DOJ: C.R. Div. (July 1, 2022), https://web.archive.org/web/20220703102420/https://www.justice.gov/crt/protecting-patients-and-health-care-providers, with Protecting Patients and Health Care Providers, DOJ: C.R. Div. (May 22, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/crt/protecting-patients-and-health-care-providers [https://perma.cc/YJ8W-SJBW] (now stating, “The FACE Act is not about abortions.”). ↑

- See Protecting Patients and Health Care Providers (2023), supra note 3. ↑

- This, of course, begs the question of whether the so-called “abortion movement” is united enough to take such a position. ↑

- Cheffer v. Reno, 55 F.3d 1517, 1519 n.2 (11th Cir. 1995) (citing to S. Rep. No. 103–117, at 3 (1993)). ↑

- See Threats Against Doctors, Feminist Majority Found., https://feminist.org/our-work/national-clinic-access-project/wanted-posters-used-to-threaten-doctors [https://perma.cc/H3MV-MVXG]; see also E.J. Dickson, How Nothing and Everything Has Changed in the 10 Years Since George Tiller’s Murder, Rolling Stone (May 31, 2019), https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/george-tiller-death-abortion-10-year-anniversary-842786 [https://perma.cc/Q376-9EE3] (documenting that Scott Philip Roeder murdered Dr. Tiller, an abortion provider, on May 31, 2009, while Dr. Tiller served as an usher at a church in his hometown). ↑

- Threats Against Doctors, supra note 7. ↑

- NAF Violence and Disruption Statistics, Nat’l Abortion Fed’n, https://www.prochoice.org/pubs_research/publications/downloads/about_abortion/violence_stats.pdf [https://perma.cc/B7M2-9DAJ]. ↑

- See id. ↑

- The Army of God Website Adds Racist Materials, So. Poverty L. Ctr. (Dec. 18, 2002), https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2002/army-god-website-adds-racist-materials [https://perma.cc/3MCY-Y6D6]. ↑

- See Woman Gets 20-Year Sentence In Attacks on Abortion Clinics, N.Y. Times (Sept. 9, 1995), https://www.nytimes.com/1995/09/09/us/woman-gets-20-year-sentence-in-attacks-on-abortion-clinics.html [https://perma.cc/RV2S-AMPM]; 3 Men Charged in Bombings Of Seven Abortion Facilities, N.Y. Times (Jan. 20, 1985), https://www.nytimes.com/1985/01/20/us/3-men-charged-in-bombings-of-seven-abortion-facilities.html [https://perma.cc/QV32-Q6QQ]. ↑

- See Provider Security, Nat’l Abortion Fed’n, https://prochoice.org/our-work/provider-security [https://perma.cc/8VK3-YALP]. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Frederick Clarkson, Anti-abortion Movement Marches on after Two Decades of Arson, Bombs, and Murder, So. Poverty L. Ctr. (Sept. 15, 1998), https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/1998/anti-abortion-movement-marches-after-two-decades-arson-bombs-and-murder [https://perma.cc/D3YB-AQUZ]; see also The Army of God, The Army of God Manual (3d ed.) https://www.armyofgod.com/AOGsel1.html [https://perma.cc/G6HK-ZX3B]. ↑

- Kimberly Hutcherson, A Brief History of Anti-Abortion Violence, CNN (Dec. 1, 2015, 7:51 AM), https://www.cnn.com/2015/11/30/us/anti-abortion-violence/index.html [https://perma.cc/52T4-RQF8] (“[V]iolence picked up dramatically in the 1990s. Anti-abortion extremists – particularly those aligned with the extremist group Army of God – began to make their position clear that killing abortion providers was the only way to stop the procedure from being performed.”). ↑

- Gene Warner, Spring of Life Fails to Live Up to Hype Yet Efforts Puts Issue in Spotlight, Buffalo News (May 3, 1992), https://buffalonews.com/news/spring-of-life-fails-to-live-up-to-hype-yet-effort-puts-issue-in-spotlight/article_cbc3b26a-c420-523b-9df0-0ed851c17826.html [https://perma.cc/2X95-JWV7]. ↑

- The Death of Dr. Gunn, N.Y. Times (March 12, 1993), https://www.nytimes.com/1993/03/12/opinion/the-death-of-dr-gunn.html [https://perma.cc/J8YH-XXDH]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, S. 636, 103rd Cong. (1994) (enacted). ↑

- Id. ↑

- 140 Cong. Rec. 3117 (1994). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 18 U.S.C. § 248(a)(1)–(3). ↑

- 18 U.S.C. § 248(e)(1). ↑

- 18 U.S.C. § 248(e)(5). ↑

- 140 Cong. Rec. 3117 (1994). ↑

- See, e.g., United States v. Brock, 863 F. Supp. 851, 856–57 (E.D. Wis. 1994), discussed infra Section I.C.1. ↑

- See supra note 3. ↑

- Protecting Patients and Health Care Providers, DOJ: C.R. Div. (Sept. 15, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/crt/protecting-patients-and-health-care-providers [https://perma.cc/H3WP-UEUH]. ↑

- See, e.g., Lucero v. Trosch, 904 F. Supp. 1336, 1342 (S.D. Ala. 1995) (finding argument that the FACE Act is facially invalid because it violates the First Amendment meritless due to the fact that the Act is “viewpoint and content neutral”). ↑

- Brock, 863 F. Supp. at 856–57. ↑

- Id. at 861 n.19. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Norton v. Ashcroft, 298 F.3d 547, 553 (6th Cir. 2002). ↑

- Id. at 551. ↑

- Id. at 553. ↑

- See United States v. Mathison, Crim. No. 95-085-FVS (E.D. Wash. 1995); Arianne K. Tepper, In Your F.A.C.E.: Federal Enforcement of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1993, 17 Pᴀᴄᴇ L. Rᴇᴠ. 489, 532–33 (1997). ↑

- Norton, 298 F.3d at 553 (quoting United States v. Soderna, 82 F.3d 1370, 1376 (7th Cir. 1996) (“A group cannot obtain constitutional immunity from prosecution by violating a statute more frequently than any other group.”)). ↑

- Raney v. Aware Woman Center for Choice, Inc., 244 F.3d 1266, 1268–69 (11th Cir. 2000). ↑

- Id. at 1269. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Norton, 298 F.3d at 553 (citing Mathison, Crim. No. 95-085-FVS (E.D. Wash. 1995). ↑

- Jeanette White, Pro-Choice Man Admits Threatening Anti-Abortion Staff, Spokesman-Review (June 6, 1995), https://www.spokesman.com/stories/1995/jun/06/pro-choice-man-admits-threatening-anti-abortion [https://perma.cc/4XF4-UQQG]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Greenhut v. Hand, 996 F. Supp. 372, 374 (D.N.J. 1998). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 375. ↑

- Id. at 376. ↑

- Id. at 375–76. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 376. ↑

- Id. (citing United States v. Hill, 893 F. Supp. 1034, 1039 (N.D.Fla. 1994) (discussing abortion clinic escorts); United States v. Dinwiddie, 76 F.3d 913, 926–27 (8th Cir. 1996) (discussing maintenance workers)). ↑

- Id. at 376. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 278 F.3d 1180, 1181 (11th Cir. 2002). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1182. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1183. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 140 Cong. Rec. 3117 (1994). ↑

- See, e.g., United States v. Gregg, 226 F.3d 253, 267 (3d Cir. 2000) (“The language of the statute and the legislative history demonstrates that FACE governs all individuals and groups that obstruct the provision of reproductive health services and religious worship,” is “view-point neutral,” and “does not discriminate on the basis of content.”). ↑

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 142 S. Ct. 2228 (2022). ↑

- Jessica Winter, The Dobbs Decision Has Unleashed Legal Chaos for Doctors and Patients, New Yorker (July 2, 2022), https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-dobbs-decision-has-unleashed-legal-chaos-for-doctors-and-patients [https://perma.cc/KF73-MF2K]. ↑

- Gabriella Borter & Costas Pitas, Thousands in U.S. March under ‘Ban Off Our Bodies’ Banner for Abortion Rights, Reuters (May 16, 2022, 5:37 AM), https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-abortion-rights-activists-start-summer-rage-with-saturday-protests-2022-05-14 [perma.cc/UUS6-GJFK]. ↑

- Supreme Court Rules on Abortion: Thousands Protest End of Constitutional Right to Abortion, N.Y. Times (June 24, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/06/24/us/roe-wade-abortion-supreme-court [https://perma.cc/M5TV-UVQX]. ↑

- Allison McCann et al., Tracking Abortion Bans Across the Country, N. Y. Times (Sept. 11, 2023, 1:30 PM), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html [https://perma.cc/QG8U-TVNG]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Public Opinion on Abortion, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (May 17, 2022), https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion [https://perma.cc/H36L-FL5U] (showing that views on abortion remained relatively stable between 1995 and 2022). ↑

- Lydia Saad, Broader Support for Abortion Rights Continues Post-Dobbs, Gallup (June 14, 2023), https://news.gallup.com/poll/506759/broader-support-abortion-rights-continues-post-dobbs.aspx [https://perma.cc/H8AS-7AK3]. ↑

- Steven Shepard, The Supreme Court Dramatically Changed Public Opinion on Abortion, Politico (June 24, 2023, 7:00 AM), https://www.politico.com/news/2023/06/24/supreme-court-public-opinion-abortion-00103493 [https://perma.cc/N5E4-Z35C]. ↑

- Demonstrators Converge Outside Supreme Court After Dobbs Decision, SCOTUSblog (Jun. 24, 2022, 6:33 PM), https://www.scotusblog.com/2022/06/demonstrators-converge-outside-supreme-court-after-dobbs-decision [https://perma.cc/4A9Z-HF4F]. ↑

- Endora, Comparative Reporting on Abortion Related Incidents 2 (2023), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WCAJS1GzbUzb5qzouBOdMQRHL0oe4B_G/view [https://perma.cc/NG8A-BJAG]. ↑

- Id. at 1. ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 5. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 6. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Recent Cases on Violence Against Reproductive Health Care Providers, DOJ: C.R. Div. (May 30, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/crt/recent-cases-violence-against-reproductive-health-care-providers [https://perma.cc/Y7XC-TED5]. There were 4 indictments in 2021, one in 2020, two in 2019, one in 2018, one in 2017, and two in 2016. Id. While, at first blush, the number of prosecutions appears to be increasing, one cannot discount the fact that a president openly hostile to abortion occupied the White House from 2016 to 2020. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Two Additional Defendants Charged with Civil Rights Conspiracy Targeting Pregnancy Resource Centers, DOJ: Off. of Pub. Affs. (Apr. 3, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/two-additional-defendants-charged-civil-rights-conspiracy-targeting-pregnancy-resource [https://perma.cc/S9Y8-VG9A]. ↑

- Indictment at 3, United States v. Freestone, No. 8:23-cr-25-VMC-AEP (M.D.Fla. July 27, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/media/1283676/dl?inline [https://perma.cc/G3QM-MF3R]. ↑

- Vandalized Wall (illustration), in Beyond Revenge, What Does Jane’s Revenge Want?, Intercept (June 16, 2022), https://theintercept.com/2022/06/16/janes-revenge-abortion-rights [https://perma.cc/YC4F-RJSZ] (similar graffiti spray-painted by Jane’s Revenge on the exterior of a CPC in Madison, Wisconsin on May 8, 2022). ↑

- Recent Cases on Violence Against Reproductive Health Care Providers, supra note 96. ↑

- Middletown Man Pleads Guilty in Federal Court to Use of Incendiary Device at Newark Planned Parenthood, DOJ: U.S. Att’y Gen.’s Off., Dist. of Del. (Feb. 15, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/usao-de/pr/middletown-man-pleads-guilty-federal-court-use-incendiary-device-newark-planned [https://perma.cc/SGR2-3RQW]. ↑

- Id.; see also Why the Far-Right and White Supremacists Have Embraced the Middle Ages and Their Symbols, Conversation (Jan. 13, 2021, 2:11 PM), https://theconversation.com/why-the-far-right-and-white-supremacists-have-embraced-the-middle-ages-and-their-symbols-152968 [https://perma.cc/F6CT-GXSZ]. ↑

- Middletown Man Pleads Guilty in Federal Court to Use of Incendiary Device at Newark Planned Parenthood, supra note 102. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Reynolds Plea Agreement at 8, United States v. Travis James Reynolds, No. l:16-cr-00490-BPG (D. Md. 2016), https://www.justice.gov/media/889966/dl?inline [https://perma.cc/FS7N-2WSC]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Recent Cases on Violence Against Reproductive Health Care Providers, supra note 96. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Julie Turkewitz & Jack Healy, 3 Are Dead in Colorado Springs Shootout at Planned Parenthood Center, N.Y. Times (Nov. 27, 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/28/us/colorado-planned-parenthood-shooting.html [https://perma.cc/AR8Q-7Q7K]. ↑

- Kelly Jo Popkin, FACEing Hate: Using Hate Crime Legislation to Deter Anti-abortion Violence and Extremism, 31 Wis. J.L. Gender & Soc’y 103, 104–05 (2017). ↑

- Id. at 109, 111–12. ↑

- See, e.g., Melissa Tribble, Free Speech off My Body: Protecting Abortion Patients and Medical Privacy in Light of the First Amendment, 54 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1687, 1694–95 (2021); Elinor Ament, Anti-abortion Protesting, 7 Geo. J. Gender & L. 663, 666–70 (2006); Lolita Youmans, Operation Rescue v. Planned Parenthood, Inc.: A Judicial Showdown over Sidewalk Counselors and First Amendment Rights, 37 Hous. L. Rev. 603, 624 (2000); Kristine L. Sendek, ‘FACE’-ing the Constitution: The Battle over the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Shifts from Reproductive Health Facilities to the Federal Courts, 46 Cath. U. L. Rev. 165 (1996). ↑

- See supra Section I.D for discussion of increased rates of violence against clinics since 2022. ↑

- Reproductive Justice, SisterSong, https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice [https://perma.cc/W4HK-TQJA]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See the Statement, Just Faith 4 A Just World, https://www.justfaith4ajustworld.org/see-the-statement [https://perma.cc/8JNW-LBWD]. ↑

- Who We Are: The Reproductive Justice Movement in 2023, https://docs.google.com/document/d/154SPNo_TlTg0431cVtkVzPhgPbVKHlbnwmHYXUSG_VY/edit [https://perma.cc/ML4H-J9QD]. ↑

- Geneva: World Health Organization, Abortion Care Guideline 31 (2022). ↑

- See Margot Sanger-Katz, et al., Who Gets Abortions in America?, N.Y. Times: The Upshot (Dec. 14, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/12/14/upshot/who-gets-abortions-in-america.html [https://perma.cc/R58Q-LFUG]. ↑

- Mathieu Benhamou, et al., Americans in 26 States Will Have to Travel 552 Miles for Abortions, Bloomberg (June 24, 2022, 8:15 PM), https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-supreme-court-abortion-travel [https://perma.cc/YYB9-S3NA]. ↑

- Protecting Patients and Health Care Providers (2023), supra note 3. Civil claims are also possible under FACE. However, it appears that the majority of civil FACE matters are carried out by well-supported and funded abortion clinics. See Recent Cases on Violence Against Reproductive Health Care Providers, supra note 96. The issue of who might have the means or desire to carry out protracted litigation remains; in particular, what patient realistically wants to expose themselves to the financial burden of maintaining such a lawsuit? Likewise, what patient would willingly open themselves up to demeaning or invasive discovery requests at the hands of an anti-abortion proponent? ↑

- Renee Bracey Sherman, People Who Have Abortions vs. the Police: It’s Time to Pick a Side, Nation (June 23, 2022), https://www.thenation.com/article/society/abortion-police [https://perma.cc/QN36-3FUJ]. ↑

- Amy G. Bryant & Jonas J. Swartz, Why Crisis Pregnancy Centers Are Legal but Unethical, AMA J. Ethics, 1 (2018), https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/why-crisis-pregnancy-centers-are-legal-unethical/2018-03 [https://perma.cc/8KW8-ZMC7] (discussing how Crisis Pregnancy Centers create ethical quandaries in the way they conduct themselves as a “medical provider”). ↑

- See Planned Parenthood Advocates of Iowa, Why are Crisis Pregnancy Centers Dangerous?, Planned Parenthood of Iowa Blog (Mar. 25, 2022, 7:01 PM), https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/planned-parenthood-advocates-iowa/blog/why-are-crisis-pregnancy-centers-dangerous [https://perma.cc/Z93T-JG3J]. ↑

- The Am. Coll. of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, Issue Brief: Crisis Pregnancy Centers 1 (2022), https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/trending-issues/issue-brief-crisis-pregnancy-centers [https://perma.cc/RM5J-BR9G] (explaining how CPCs falsely advertise to create the appearance of a healthcare provider that will provide an abortion). ↑

- Professor Gruber teaches criminal law, criminal procedure, and critical race theory. Bio for Aya Gruber, Professor of Feminism, Criminal Law & Critical Race Theory, Aya Gruber, https://www.ayagruber.com/about-aya-gruber [https://perma.cc/4ZQG-PTFC]. As a lifelong feminist, a former public defender, a professor of criminal law for eighteen years, and a survivor, she has personally and professionally grappled with the issue of feminism’s influence on criminal law for decades. Id.; see also, Aya Gruber, The Feminist War on Crime, 92 Iowa L. Rev. 741, 748 (2007); Aya Gruber, #Metoo and Mass Incarceration, 17 Ohio St. J. Crim. L. 275, 278 (2020). ↑

- Aya Gruber, Rape, Feminism, and the War on Crime, 84 Wash. L. Rev. 581, 581 (2009). ↑

- See, e.g., Popkin, supra note 112, at 111–12 (advocating for bolstered state criminal law to work in tandem with the FACE Act). ↑

- Gruber, supra note 131, at 615. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 616. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Protecting Patients and Health Care Providers (2023), supra note 3 (“The FACE Act is not about abortions. The statute protects all patients, providers, and facilities that provide reproductive health services, including pro-life pregnancy counseling services and any other pregnancy support facility providing reproductive health care.”). ↑

- See, e.g., Jenny Zhang, Mutual Aid Groups Supported Communities When the Government Wouldn’t, Harper’s Bazaar (Mar. 9, 2021) https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a35232889/mutual-aid-groups-covid-19-pandemic [https://perma.cc/FYD5-HW3F] (discussing the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast Program during the late 1960s and early 1970s and the Puerto Rican young Lords tuberculosis testing in New York City in the 1970s). ↑

- Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, Toolkit: Mutual Aid 101, at 1, https://mutualaiddisasterrelief.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NO-LOGOS-Mutual-Aid-101_-Toolkit.pdf [https://perma.cc/5EW9-63S4]. ↑

- Dean Spade, Solidarity Not Charity: Mutual Aid for Mobilization and Survival, 38 Soc. Text 131, 136 (2020). ↑

- Id. at 136. ↑

- I would be remiss if I did not raise the issue of abortion access for those who live in areas with no abortion clinics—either because abortion has been outlawed in that locality or simply because the area is rural or isolated. My conception of community organizing remains the same but would instead center its focus on practical- and logistical-support organizations that work to assist abortion seekers in obtaining abortions in legal states or in safely managing an abortion at home with FDA-approved medication. Such organizations typically provide access to birth control, emergency contraception, and pregnancy support as well. ↑