Open PDF in Browser: Jason Anthony Robison,* Equity Along the Yellowstone

As one of three major rivers with headwaters in the sublime Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the Yellowstone and its tributaries are subject to an interstate compact (a.k.a. “domestic water treaty”) litigated from 2007 to 2018 in the U.S. Supreme Court in Montana v. Wyoming. Four tribal nations exist within the 71,000 square‑mile Yellowstone River Basin: the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne. Yet, the Yellowstone River Compact, ratified in 1951, more than a decade before the self‑determination era of federal Indian policy began, neither affords these tribal sovereigns representation on the Yellowstone River Compact Commission nor clearly addresses the status of their water rights within (or outside) the compact’s apportionment. Such marginalization is systemic across Western water compacts. Devised as alternatives to original actions for equitable apportionment before the U.S. Supreme Court, this Article focuses on the Yellowstone River Compact and its stated purpose of “equitable division and apportionment,” reconsidering the meaning of “equity,” procedurally and substantively, from a present‑day perspective more than a half‑century into the self‑determination era. Equity is a pervasive and venerable norm for transboundary water law and policy contends the Article, and equity indeed should be realized along the Yellowstone in coming years, both by affording the basin tribes opportunities to be represented alongside their federal and state co‑sovereigns on the Yellowstone River Compact Commission, as well as by clarifying the status of and protecting the basin tribes’ water rights under the compact’s apportionment.

In Memoriam: Charles Wilkinson (1941–2023). “Last, do not doubt that all of this comes back to law, for our society lodges its best dreams in laws. Too few of our laws call out the highest in us, too few call out the highest in the many sacred places that make up the American West, and we would do ourselves and our children proud by insisting with all of our worth that our laws be worthy of this wondrous place.” Law and the American West: The Search for an Ethic of Place, 59 U. Colo. L. Rev. 401, 425 (1988).

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone†

Introduction

“[N]estled within the largest relatively intact temperate zone ecosystem on the planet,” the Yellowstone begins its life as a river in an area where millions of people flock every year to fall head over heels in love with the place: the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.[1] The river’s headwaters lie in the Absarokas, near the southern edge of the first national park established in U.S. history, where the river carves the beyond‑words Grand Canyon painted famously by Thomas Moran to persuade Congress in 1872 to “[dedicate] and set apart as a public park, or pleasuring‑ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” a sublime portion of the Yellowstone plateau.[2] Glancing farther downstream, the Yellowstone is “commonly referred to as the longest free‑flowing river in the lower 48 United States, as there are no major dams or reservoirs on the mainstem.”[3] For these superlative qualities and many others, this beautiful, life‑giving water body has been hailed as a “national resource . . . without parallel.”[4]

Native peoples have known the river since time immemorial. Its uppermost segment has been called lichìilikaashaashe (Elk River) by the Apsáalooke (Crow), carving Xakupkaashe (Big Canyon, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone) and falling through that magical stretch, intensely and wonderfully, just downstream of lichìilikaashaase Ko’Bilichk’esh (Lake at Elk River, Yellowstone Lake)—or, as the Shoshone have referred to it, Bahn doy fooin (Water coming out).[5] No doubt these Native connections—this intergenerational place‑based knowledge—exist not just with respect to the Yellowstone in its majestic headwaters, but extend in equal measure to the entirety of the landscape encompassed by the river’s 71,000 square‑mile basin.[6] Tribal homelands span across and adjacent to this mixed landscape of high peaks and rolling plains, including those of the four tribal nations within the basin: the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho on the Wind River Reservation in present‑day Wyoming, and the Crow and Northern Cheyenne on their neighboring reservations in present‑day Montana.[7]

Driving this Article are a couple of observations about the basin tribes made by the late, great Charles Wilkinson, in his book The Eagle Bird, more than thirty years ago. What Charles had to say concerned the interstate compact applicable to the Yellowstone[8] and its tributaries, the Yellowstone River Compact,[9] and some unsettling aspects of the tribal nations’ circumstances under that document.[10] Charles couched his observations in ethical terms, rooting them in what he described as an “ethic of place,” for which he advocated in prose reflecting a deep love of western North America and a passionate and tireless commitment to realizing the region’s potential in inclusive, holistic, and evenhanded ways:

We need to develop an ethic of place. It is premised on a sense of place, the recognition that our species thrives on the subtle, intangible, but soul‑deep mix of landscape, smells, sounds, history, neighbors, and friends that constitute a place, a homeland. An ethic of place respects equally the people of a region and the land, animals, vegetation, water, and air. It recognizes that westerners revere their physical surroundings and that they need and deserve a stable, productive economy that is accessible to those with modest incomes. An ethic of place ought to be a shared community value and ought to manifest itself in a dogged determination to treat the environment and its people as equals, to recognize both as sacred, and to insure that all members of the community not just search for but insist upon solutions that fulfill the ethic.[11]

Channeling John Wesley Powell from a century prior,[12] Charles further suggested, “[t]he most relevant boundary lines for an ethic of place in the American West accrue from basin and watershed demarcations”—the Yellowstone River Basin and otherwise—while disavowing the notion of “rework[ing] our angular state lines to conform to river basins.”[13]

Applying this ethic of place to the Yellowstone River Compact, two aspects of the basin tribes’ circumstances troubled Charles, one having to do with marginalization of the tribes’ water rights, the other involving marginalization of the tribal nations as co‑sovereigns. As an initial matter, “tribal rights were expressly excluded from the compact,” and, “[a]s a result, many knowledgeable observers believe that the interstate allocation of the river may need to be reexamined in light of tribal water rights.”[14] Compounding this substantive concern, in Charles’s view, was a procedural matter. The body established to administer the compact, the Yellowstone River Compact Commission (the “Commission”),[15] consists solely of state and federal representatives, with no representation for the basin tribes. No legal barrier stood in the way of such representation, according to Charles, which if provided, would fully recognize “the tribes’ status as sovereign governments within the constitutional system.”[16] That is what Charles ultimately advocated, devoting a handful of paragraphs to the subject, “for a different kind of compact than those in the past,” with the end goal already identified: fulfillment of an ethic of place.[17]

Charles was not alone in recognizing these issues—as revealed nearly a quarter century later in Montana v. Wyoming, an original action before the U.S. Supreme Court from 2007 to 2018,[18] where the Northern Cheyenne, Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota expressed contrary views on the status of tribal water rights under the Yellowstone River Compact. “Thankfully,” explained the Special Master, “it is ultimately unnecessary to decide how the Compact treats Indian rights in order to resolve the current dispute between Montana and Wyoming.”[19] The Special Master’s rationale was jurisdictional—neither the U.S. nor the tribe was a party or had waived sovereign immunity[20]—and the Justices agreed.[21]

From my perspective, the absence of tribal representatives on the Yellowstone River Compact Commission, as well as the uncertain, contested status of the basin tribes’ water rights under the compact, undermine the fundamental purpose for which interstate water compacts originated during the early twentieth century: “equitable apportionment”—that is, as alternative instruments for achieving equitable apportionment along interstate rivers rather than seeking U.S. Supreme Court decrees.[22] “Equitable division and apportionment” is plainly stated as one of the Yellowstone River Compact’s core purposes, alongside “interstate comity” and a desire “to remove all causes of present and future controversy . . . with respect to the waters of the Yellowstone River and its tributaries.”[23] Yet neither these purposes nor the basin tribes’ treatment distinguish the compact; rather, the marginalization just noted is systemic.[24]

Viewing equity as a synonym for fairness,[25] this Article contends that it is unfair for the Yellowstone River Basin’s tribal nations not to be represented directly alongside their federal and state co‑sovereigns on the Yellowstone River Compact Commission—if each tribe so wishes—and likewise that it is unfair for the status of the basin tribes’ water rights within (or outside) the compact’s apportionment to be left indeterminate. Equity should look different in the twenty‑first century—or, put another way, seventy‑five years into the compact’s life as a creature of law,[26] and more than a half‑century into the self‑determination era of federal Indian policy.[27] Equity is indeed a venerable norm for transboundary water law and policy, at both the domestic and international levels,[28] and making it real along the Yellowstone (and other rivers) at this point in time requires not only willingness to acknowledge historical injustices of water colonialism,[29] but, of equal importance, intentionality to approach future transboundary water management with proper respect for Indigenous peoples such as the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne. That is what fundamentally needs to happen in my view, and the pages below gradually unfold this argument.

Conveying a sense of place is essential, especially for readers who care deeply and fervently about environmental justice, yet may not have had the privilege of spending time in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem or the vast expanse of basin and range country stretching northeasterly across the river’s basin.[30] Part I paints this picture. It focuses partly on the Yellowstone River Basin’s physical, political, and human geography, including the basin tribes’ reservations,[31] and partly on something currently garnering unprecedented attention: climate change and its impacts near the Yellowstone’s headwaters and across the Northern Plains.[32]

With the stage set in this way, the discussion shifts in Part II to compacts—the principal instruments forged under the U.S. Constitution to mediate co‑sovereign relations over transboundary rivers such as the Yellowstone.[33] Shedding light on their constitutional roots[34] and general nature as legal instruments,[35] the discussion delves into the specific compact at the heart of this piece. The Yellowstone River Compact’s genesis from 1932 to 1951 is surveyed,[36] followed by coverage of the contemporary eras of federal Indian policy,[37] and ultimately the compact’s legal architecture—specifically, its governance structure in Article III,[38] and its interstate apportionment and treatment of tribal water rights in Articles V and VI, respectively.[39] This overview serves as an essential backdrop for my advocacy addressing the marginalization highlighted above concerning “equitable division and apportionment.”[40]

Equity, as a norm and hopefully a reality, is where the discussion eventually leads in Part III. What exactly should “equity” mean in the context of interstate water compacts? Answers assuredly vary, and the Part begins by offering one way of thinking about this subject, a framework where equity is broken into procedural and substantive categories, both of which recognize how perceptions of fairness are shaped by multiple factors and inherently tied to historical context.[41] This framework is then applied to advocate for (1) representation of the basin tribes as co‑sovereigns on the Yellowstone River Compact Commission if they so wish,[42] and (2) clarification of the status of, and protection for, the basin tribes’ water rights under the compact’s apportionment.[43] In critical ways, both prescriptions involve the trust relationship shared by the U.S. and all tribal sovereigns, including the basin tribes, ever since this nation‑state’s founding.[44] So, too, are the prescriptions shaped by the current era of federal Indian policy—again, the self‑determination era—and the basic idea that equity needs to be conceptualized at present in ways that further rather than undermine key policy priorities of this era—namely, respect for tribal self‑governance, sovereignty, and self‑determination.[45]

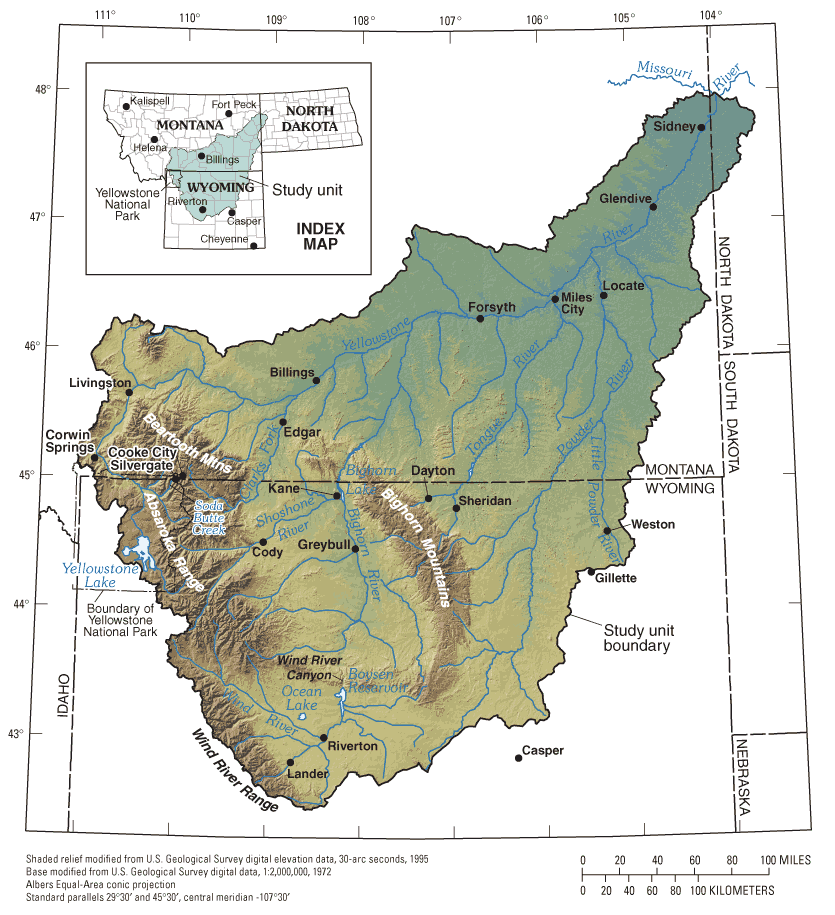

Looking ahead, this preview’s bird’s‑eye perspective dovetails with that provided by the map below—an entry point into the Yellowstone River and its vast basin.

Figure 1. Yellowstone River Basin[46]

I. lichìilikaashaashe & Its Basin

It is impossible, at least for me, not to visualize the headwaters of the Yellowstone River—Yellowstone Lake, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,[47] and adjacent high‑altitude areas of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem[48]—when thinking about the future of the interstate compact apportioning use of the river system’s flows, including the compact’s treatment of Native peoples and their water rights. This place truly is magical, and the discussion below aims to capture some of its captivating character while also surveying the critical topic of climate change and its historical and projected impacts within the basin.

A. Sense of Place

Originally referred to as the “Roche Jaune” (“Yellow Rock”), the Yellowstone River’s name reflects a translation of the Native term Mi tse a‑da‑zi,[49] accounting for the “long miles of seething river flow[ing] past high cliffs of yellow sandstone.”[50] The nearly 700‑mile‑long river is one of stark contrasts—put differently, topographical relief is large.[51] Within its Grand Canyon,[52] Yellowstone Falls (Upper and Lower) embody the river’s dynamic and incisive character in its upper reaches, dropping nearly 2,000 feet in the initial ten miles of its descent from the slopes of Younts Peak (elevation 12,156 feet),[53] flattening out across a roughly 60‑mile section where it forms North America’s largest high‑elevation lake,[54] and then abruptly plunging another 1,200 feet through the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone to the national park’s northern boundary.[55] Downstream of Livingston, Montana, the scene is much different, with the river meandering northeasterly at a mellowed gradient and lowering in elevation to 3,000 feet at Billings, 2,800 feet at its confluence with the Big Horn River, and 1,850 feet at its mouth.[56]

Mirroring this contrasting character are the Yellowstone’s tributaries—the Clarks Fork, Wind/Bighorn, Tongue, and Powder rivers—and the basin encompassing the river system as a whole. With headwaters in the Absaroka, Beartooth, Bighorn, and Wind River ranges,[57] the tributaries follow the general pattern just sketched, descending from breathtaking, high‑elevation peaks to lower‑lying interior valleys and plains, and flowing northeasterly in varied ways to join the Yellowstone River as it stretches across southeastern Montana to its confluence with the Missouri River at North Dakota’s far western edge.[58] At this spot, with all tributaries having joined the mainstem, the Yellowstone River contributes about 55 percent of the Missouri River’s water volume and constitutes its largest tributary.[59] Overall, the 71,000 square‑mile basin is a place where the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains meet,[60] with roughly 51 percent of the land base in Montana, 48 percent in Wyoming, and 1 percent in North Dakota.[61]

While no large‑scale dams and reservoirs impound the Yellowstone River itself, water infrastructure does exist across the basin,[62] most prominently in its western headwaters.[63] Total basinwide storage capacity is approximately 3,450,000 acre‑feet—2,010,000 acre‑feet in Wyoming, and 1,446,400 acre‑feet in Montana.[64] Along the Yellowstone, “irrigation diversions composed of rock or concrete typically block or partially block the main channel,” with “several large pump stations on the channel banks and dozens of small pumps and headgates” supporting irrigation.[65] More monumental in stature, the highest dam of the entire Missouri River Basin, the 525‑foot Yellowtail Dam, stretches as a massive concrete arch across the Bighorn River, roughly one hundred miles upstream of its confluence with the Yellowstone, forming an extensive reservoir, Bighorn Lake, with 1,331,725 acre‑feet of storage capacity.[66] Upstream counterparts in the Wind/Bighorn Basin include Buffalo Bill Dam and Reservoir along the Shoshone River and Boysen Dam and Reservoir along the Wind River, bearing storage capacity of 644,540 and 745,851 acre‑feet, respectively.[67] Farther to the east, on the other side of the Bighorns, lies Tongue River Dam and Reservoir, with 79,070 acre‑feet of storage capacity.[68]

These dams and reservoirs enable a variety of beneficial uses of the river system’s flows by human beings, but neither the plumbing nor other aspects of the human presence have come without costs to ecosystems.[69] In a host of ways, the water infrastructure and related human activities have impacted aquatic and riparian ecosystems throughout the basin:

The Yellowstone River’s natural snow‑melt driven hydrograph has been altered, [its] longitudinal, lateral, and main stem to tributary connectivity has been reduced, a variety of structures such as bank revetments (i.e., riprap), flow deflection structures (barbs, jetties, spur dikes, etc.) and flow confinement structures (i.e., levees, berms, dikes, etc.) have been installed along the banks and in the floodplain, and several nonnative fish are present. In addition, the riparian zone has been invaded by a number of invasive plant species such as Russian Olive and Salt Cedar that can have significant adverse effects on terrestrial habitat near water bodies.[70]

In terms of flow levels, the Yellowstone River Basin produces an estimated average of ten million acre‑feet annually.[71] Roughly 80 percent of this runoff originates in Wyoming’s mountains and flows into Montana through the tributaries just mentioned—from west to east, the Clarks Fork, Wind/Bighorn, Tongue, and Powder rivers.[72] Approximately 20 to 25 percent of the runoff is consumed each year.[73] Reflective of the landscape’s rural character—Billings, Montana being the largest community with 117,116 of the basin’s roughly 320,000 residents[74]—more than 90 percent of basinwide withdrawals go to irrigated agriculture.[75]

With respect to water quality, “[a]s the cumulative drain for the basin, the Yellowstone River integrates water quality characteristics of all land uses and human activities in its many tributaries.”[76] Water‑quality‑impaired river segments and lakes or reservoirs exist throughout the basin,[77] and significant water quality issues affecting both surface water and groundwater include trace elements, toxic compounds, salinity, sedimentation, bacteria, and nutrient concentrations.[78]

The three states through whose territory the Yellowstone River and its tributaries run (basin states) were identified above: Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota. Large and rectangular, in whole or part, these states were etched onto the western landscape in 1889 and 1890,[79] close to a century after the U.S. entered into the 1803 Louisiana Purchase with France.[80] It was only a few years later that William Clark carved his signature into Pompeys Pillar along the Yellowstone during the Corps of Discovery’s 1806 return from the Pacific,[81] and John Colter took leave of the expedition to undertake his unrecorded excursions into the Yellowstone country (“Colter’s Hell” and elsewhere) during 1807 and 1808.[82] A provision of the Enabling Act facilitating Montana’s and North Dakota’s statehood is notable:

[T]he people inhabiting said proposed States do agree and declare that they forever disclaim all right and title to the unappropriated public lands lying within the boundaries thereof, and to all lands lying within said limits owned or held by any Indian or Indian tribes; and that until the title thereto shall have been extinguished by the United States, the same shall be and remain subject to the disposition of the United States, and said Indian lands shall remain under the absolute jurisdiction and control of the Congress of the United States.[83]

The Montana and North Dakota constitutions incorporate this provision.[84] Wyoming also included it in its constitution,[85] though the provision did not appear in its statehood act.[86]

Native peoples’ presence in the Yellowstone River Basin, of course, traces back millennia, to time immemorial,[87] and can be gleaned in modern times by (among other things) the three reservations on which the basin tribes reside. Uniformly, these reservations had been created before Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota became states.[88] In Wyoming’s portion of the basin lies the Wind River Reservation, on which the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho reside, created by the Second Treaty of Fort Bridger in 1868.[89] The Wind River and its tributaries flow down the eastern slope of the same‑named mountain range through this reservation and eventually into Boysen Reservoir.[90] Established almost contemporaneously by treaty in 1868,[91] the Crow Reservation sits farther north in the Wind/Bighorn Basin, abutting the state line from the Montana side.[92] The Crow Reservation contains Yellowtail Dam—impounding the Bighorn River into Bighorn Lake for seventy‑one miles upstream[93]—as well as tributary segments such as the Little Bighorn River.[94] Immediately to the east of the Crow Reservation is the Northern Cheyenne Reservation—created by executive order in 1884[95]—whose eastern boundary is marked by the Tongue River just downstream of Tongue Reservoir.[96]

B. Sense of Change

The Yellowstone River Basin’s climate has been changing. The metrics of Western science used to track this pattern dovetail with what Crow elders have shared during interviews about changes they have observed in weather patterns and ecosystems across their lifetimes: “[F]ar less snowfall and milder winters, increased spring flooding, hotter summers,” and “extreme, unusual, and unpredictable weather events, compared to earlier times when seasons were consistent year after year.”[97] Fairly dense and quantitative in nature, the discussion below details how the river system of today (and tomorrow) differs from 1950 when the Yellowstone River Compact was drafted, as well as how a host of serious climate‑related water management issues confront the basin—and thus, inherently, the compact itself.

Serving as a fitting entry point for this material is, again, the theme of contrasts, in this case as it relates to basinwide temperature and precipitation. “Climate in the Yellowstone River Basin ranges from cold and moist in the mountainous areas to temperate and semiarid in the plains areas.”[98] Specifically, “[a]nnual temperature extremes range from about ‑40°F during the winter to hotter than 100°F during the summer,”[99] while “[m]ean annual temperatures range from less than 0ºC (32ºF) to 10ºC (50ºF).”[100] Temperatures are coldest in January (averaging from ‑18 degrees Celsius (0 degrees Fahrenheit) to ‑3 degrees Celsius (27 degrees Fahrenheit)) and warmest in July (averaging from 12 degrees Celsius (54 degrees Fahrenheit) to 24 degrees Celsius (75 degrees Fahrenheit)).[101] Precipitation, too, varies widely, in both quantity and form. “Mean annual precipitation ranges from more than 70 inches at high elevations in the mountains near Yellowstone National Park . . . to 5.5 inches in the central parts of the Bighorn and Wind River Basins.”[102] Snowpack is the source of most runoff,[103] as discussed further below, and “average annual snowfall rang[es] from less than 12 inches in parts of the Bighorn Basin to more than 200 inches near Yellowstone National Park.”[104] The headwaters mountains store water from October through May, and “[t]his water is released in April through August, with most runoff occurring in the spring‑summer snowmelt flood that typically peaks in mid to late June.”[105] In contrast, “[o]ther streams originate in the plains,” many of which are intermittent or ephemeral, such that “sporadic higher flows are the result of local snowmelt or intense rainstorms.”[106]

The Yellowstone River Basin’s foregoing variability should not be viewed as implying stationarity across time, particularly with respect to climate change’s historical and projected impacts on temperature. Mean annual temperature in the portion of the basin above Billings, Montana, has increased steadily since the mid‑twentieth century, from about 37 degrees Fahrenheit in 1950 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit in 2014.[107] Looking ahead, projections for future temperature increases in this portion of the basin vary by model and scenario, with a median increase of 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit and a range of 1.2 to 4.9 degrees Fahrenheit for the 2010 to 2059 period, as compared to the 1950 to 1999 period.[108] Similar observations and projections can be found in climate research on the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA), including the Upper Yellowstone and Big Horn watersheds.[109] Across the GYA, “[t]he average temperature of the last two decades (2001–2020) is probably as high or higher than any period in the last 20,000 [years], and likely higher than previous glacial and interglacial periods in the last 800,000 [years].”[110] Further, since 1950, “[m]eteorological records, averaged across the GYA, show that the mean annual temperature in the GYA has increased by 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.3 degrees Celsius) at a rate of 0.35 degrees Fahrenheit (0.19 degrees Celsius) per decade.”[111] While there is variation among models and scenarios, this pattern is projected to continue going forward, with GYA temperatures increasing, as compared to the 1986 to 2005 period, by 5.3 degrees Fahrenheit under one pathway (RCP4.5) and 10.0 degrees Fahrenheit under another pathway (RCP8.5), by 2099.[112] Projected temperature increases for the Upper Yellowstone and Big Horn watersheds track these projections for the entire GYA.[113] This trend, historical and projected, has significant implications for water management across the basin, particularly the agricultural sector, including an extended growing season,[114] increased evaporation from soil and reservoirs, and increased evapotranspiration by irrigated crops and natural vegetation.[115]

Climate change also has impacted, and is projected to continue impacting, basin‑wide precipitation.[116] Annual precipitation appears to have increased slightly above Billings, Montana since the mid‑twentieth century, from about 25 to 27 inches annually.[117] Looking ahead, projections for future precipitation in this area vary more than those for temperature. The median projection for the 2010 to 2059 period, relative to the 1950 to 1999 period, is an increase of 1.1 inches (2.4 percent).[118] Within the GYA, annual precipitation averaged 26.7 inches from 1986 to 2005.[119] Moving forward, projected precipitation differs in extent but not general trajectory. Relative to the 1986 to 2005 period, mean annual precipitation in the GYA is projected to increase 7 percent by mid‑century (2041–2060) and 8 percent by the end of century (2081–2099) under the RCP4.5 pathway.[120] Over the same periods, but under the RCP8.5 pathway, the projected increases are 9 and 15 percent, respectively.[121] Projected precipitation increases within the Upper Yellowstone and Big Horn watersheds resemble these projections for the whole GYA.[122]

These precipitation figures are closely intertwined with those addressing climate change’s impacts on snowfall—as noted, “[s]nowfall is the primary source of runoff to the Yellowstone River.”[123] Temperature and snowfall have an inverse relationship: “As the climate has warmed, mean annual snowfall in the GYA has declined by 3.5 inches” per decade, and much of this decline has occurred in spring when warming has been greatest.[124] Snowfall declines within the GYA have been pronounced in January and March,[125] and “the snow‑free season has lengthened[,] with snow accumulation in June and September declining to near zero.”[126] All told, from 1950 to 2018, there was a 24‑inch decrease in annual snowfall across the GYA, including a 7.4‑inch decrease in the Big Horn watershed, yet a 1.4‑inch increase in the Upper Yellowstone watershed.[127] This pattern reflects the trend across the Northern Rockies: “Warmer spring temperatures coupled with increased variability of spring precipitation correspond strongly to earlier snow melt‑out, an increased number of snow‑free days, and observed changes in streamflow timing and discharge.”[128] As the twenty‑first century progresses, snowfall is projected to continue decreasing across the GYA, again subject to variation among models and scenarios. Specifically, under the RCP4.5 pathway, the portion of the GYA dominated by winter snowfall is projected to decrease from 59 percent during the 1986 to 2005 base period to 27 percent at mid‑century (2041–2060)[129] and 11 percent by the end of century (2081–2099).[130] Even more drastic, under the RCP8.5 pathway, the extent of snow‑dominant area across the GYA is projected to decrease to 17 percent and 1 percent, respectively, for the same periods.[131] Similar projections exist for the Upper Yellowstone and Big Horn watersheds.[132]

What do these changes mean for runoff in the Yellowstone River system? Here is a useful encapsulation: Rather than the river system’s flows being stationary in coming decades, “[a]n overwhelming preponderance of scientific evidence shows that the future envelope of streamflow variability will differ from the historical. . . . [S]treamflow is likely to change, in amount, timing and distribution.”[133] With respect to the headwaters, data for the Yellowstone River at Livingston, Montana, reveal that “over the past 15 years, runoff has typically started about a week earlier and peaked 10 days earlier than it typically did between 1896 and 1990.”[134] On a state-wide basis in Montana, including along the Yellowstone, “virtually all model simulations developed in support of the state water plan project predict earlier runoff and reduced summer flows.”[135] The GYA climate research is similar. From 1950 to 2018, peak streamflow occurred eight days earlier across the GYA as a whole, twelve days earlier in the Upper Yellowstone watershed, and one day earlier in the Big Horn watershed.[136] Looking ahead to 2100, summer runoff is projected to decline by 35 percent across the entire GYA, and by 32 percent and 36 percent in the Big Horn and Upper Yellowstone watersheds, respectively.[137] In addition, as alluded to above, the growing season is projected to extend forty days longer in the Big Horn watershed and thirty‑five days longer in the Upper Yellowstone watershed by 2100.[138]

Much more could (and should) be said about climate change within the Yellowstone River Basin, but hopefully this discussion hits some of the high points, historical and projected, including the conjoined, pronounced basin‑wide increases in temperatures, declines in snowfall, and declines in summer runoff. Simply put, climate change is water change along the Yellowstone—the river of 1950 is not the river of 2025 or 2100—and stakeholders understandably have expressed anxiety about future water management.[139] “We conducted a survey with all of our 850 rural families,” described a tribal member in the Upper Yellowstone watershed, “and their biggest concern is water. Water is a big concern for everybody.”[140] It is a truism to say that this concern bears directly and in multifaceted ways on the interstate water compact developed amidst the Cold War to allocate the river system’s flows.

II. Of Cold Wars & Domestic Water Treaties

Thinking about what future water management might look like along the Yellowstone not only requires surveying the physical landscape as outlined above but also the legal landscape as canvassed below, particularly the now seventy‑five‑year‑old Yellowstone River Compact. An initial aspect of this task involves delving into legal history, both pertaining to the compact’s formation, as well as contemporary federal Indian policy. Against this historical backdrop, a subsequent and equally essential aspect entails analyzing the compact’s legal architecture—specifically, the design of its governance structure and apportionment, including its respective treatment of the basin’s tribal sovereigns and their water rights.

A. Vignette of the Yellowstone River Compact’s Genesis

Putting together a compact for the Yellowstone River system was no small feat during the mid‑twentieth century. In the big picture, this protracted endeavor can be traced to a taxing and suboptimal experience endured by a famous attorney from Greeley, Colorado, Delph Carpenter, the “father of interstate water compacts,”[141] hammering out interstate relations over the Laramie River before the U.S. Supreme Court in Wyoming v. Colorado.[142] Responding to this litigation, Carpenter (a.k.a. the “Silver Fox of the Rockies”)[143] initially proposed during the early 1920s navigating western states’ relations over interstate rivers by utilizing the U.S. Constitution’s Compact Clause,[144] rather than invoking the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction.[145] Carpenter’s advocacy clearly articulated his views on federalism in regard to Western water and, concomitantly, the fundamental nature of interstate compacts as then‑novel legal instruments:

If the separate sovereignties (the States) in Union only for Federal purposes have and do possess and exercise the powers to formulate and conclude binding conventions between each other and between one or more thereof and the Federal Government respecting boundaries, fisheries, harbor control and pollution, interstate easements and servitudes, and like subjects, there can be no logical objection to the application of like methods of solution to all problems growing out of the use and distribution of the waters of interstate streams. . . . All such problems respecting international rivers are settled by conventions between the nations whose territory is involved. The factors which prompt such methods between independent nations should apply between States of separate sovereignties and exclusive jurisdictions, yet bound together in a Federal Union of limited and delegated powers under a Constitution of their own creation.[146]

Carpenter’s theorizing here forever shaped the contours of Western water law.

Fast‑forwarding nearly three decades, Carpenter’s view of compacts as domestic water treaties provides a well‑suited backdrop for the Yellowstone River Compact’s formation. Steeped in parochialism and frustration, witness the remarks of an unnamed Montana resident, read into the congressional record on August 26, 1949, responding to statements by former Wyoming State Engineer L.C. Bishop[147] that had expressed support for forming a compact for the Yellowstone River system, in lieu of U.S. Supreme Court litigation:

To go back to Mr. Bishop again, he says that he doesn’t believe the States should have a lawsuit over this water, but that they should continue to try to negotiate compacts. This particular compact appears to me to be about the same thing as one would experience in trying to negotiate a compact with Joe Stalin. As far as I am concerned, the two States have been involved in a cold war for some time.[148]

During the roughly thirty‑year period between Delph Carpenter’s early advocacy for interstate water compacts and that Montana resident’s “cold war” remarks, a compact had begun to emerge, albeit in fits and starts, for the Yellowstone River system. To put a finer point on it, in its current form, “[t]he Yellowstone River Compact is the result of three earlier attempts to get an agreement on the allocation and use of the waters of the Yellowstone Basin.”[149]

Across this period, from 1932 to 1951, a familiar motive notably persisted, one common across Western water compacts. The Yellowstone River Compact’s formation was not an abstract exercise in collaborative design of transboundary water institutions, but rather a prerequisite for federally supported basin‑wide water infrastructure and development.[150]

With this motive ever present, the first round of compact negotiations spanned the mid‑1930s, commencing on June 14, 1932, when Congress authorized Montana and Wyoming to enter into a compact “for an equitable division and apportionment . . . of the water supply of the Yellowstone River and of the streams tributary thereto.”[151] January 1, 1936, was set as a deadline.[152] It came and went. Commissioners for Montana and Wyoming, as well as a commissioner for the U.S., negotiated and signed a compact in Cheyenne on February 6, 1935.[153] But as described several years later by former Wyoming Governor Lester C. Hunt: “We have no record of this [compact] having been submitted to the State Legislatures for ratification.”[154] Thus ended the first attempt.

The next foray—the second round of compact negotiations—stretched from 1937 to 1942. Congress’s authorization of negotiations on August 2, 1937, resembled its counterpart five years prior, imposing June 1, 1939, as a deadline for Montana and Wyoming to form a compact “for an equitable division and apportionment . . . of the water supply of the Yellowstone River and of the streams tributary thereto.”[155] Yet a couple things changed as this stretch of the negotiations ran its course. The original deadline went unmet as before, and thus was amended to June 1, 1943, and North Dakota also was authorized to participate in the negotiations.[156] Notwithstanding these developments, no compact ultimately made it over the finish line. On New Year’s Eve of 1942, a compact was signed by the commissioners in Billings, Montana, but the legislatures of that state and North Dakota later declined to ratify it.[157]

Likewise, contrary to the old saying, the third round of negotiations was not a charm. Congress extended to June 1, 1947, the deadline for negotiating a compact for the Yellowstone River system, in this instance with Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota all participating from the outset.[158] Less than a year passed before the state commissioners, joined by the commissioner for the U.S., negotiated and signed another compact in Billings.[159] Following the turn of the year, in early 1945, the Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota legislatures each ratified the compact.[160] But still it was not to be, as Wyoming’s governor vetoed it.[161]

It was in this specific context—seventeen years after Congress initially had authorized compact negotiations, and five years after the 1944 version had failed to come into being—that the remarks of the unnamed Montana resident mentioned above, analogizing the experience to a “cold war” with “Joe Stalin,” were read into the congressional record.[162] Roughly three months earlier, on June 2, 1949, Congress yet again had given its blessing for Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota to enter into a compact “providing for an equitable division and apportionment . . . of the water supply of the Yellowstone River and of the streams tributary thereto.”[163] A deadline of June 1, 1952, had been set and, on this occasion, it did not go by the wayside. A sequence of formal meetings was held in Billings on November 29, 1949; February 1–2, 1950; October 24–25, 1950; and December 7–8, 1950.[164] At the last meeting’s close, the state commissioners signed the compact,[165] setting the stage for the final hurdle, federal and state ratification, in what at that point had become a nearly two‑decade‑long project. All told, the basin states’ legislatures ratified the compact, with their respective governors conferring approval, during the first few months of 1951.[166] Congress followed suit—as required by the U.S. Constitution’s Compact Clause[167]—about six months later, on October 30, 1951.[168]

What exactly did this nearly two‑decade‑long endeavor yield? How did the version of the compact finalized in 1951 call for apportioning use of the Yellowstone River system’s flows, and who would have a hand in administering the apportionment, including resolving potential conflicts over it? These questions point to where the discussion now turns.

B. “Equitable Division & Apportionment”

As identified earlier, not only did the phrase (norm, really) “equitable division and apportionment” appear throughout Congress’s acts authorizing negotiation of a Yellowstone River Compact from 1932 to 1951,[169] the phrase also cannot be missed in a portion of the compact’s preamble expressing the basin states’ desire “to provide for an equitable division and apportionment” of the “waters of the Yellowstone River and its tributaries.”[170] This foundational goal cannot be separated from the particular approaches taken by state and federal negotiators when shaping the compact’s governance structure and apportionment. Further, how equity was conceived in these respects—as an aspirational norm and vis‑à‑vis the governance structure and apportionment—inherently reflects the time and space in which the compact was formed, including the contemporary eras of federal Indian policy.

1. Federal Indian Policy: Allotment & Assimilation to Termination Eras

To elaborate, while the discussion below delves into key features of the Yellowstone River Compact’s governance structure and apportionment involving equity (procedural and substantive),[171] it should be highlighted at the outset that the compact’s negotiation commenced at the seam of two eras of federal Indian policy—the allotment and assimilation era followed by the Indian reorganization era—while the compact’s ultimate adoption took place during the termination era.[172] Analogous to a pendulum’s swing,[173] the shift in policy across these eras reveals approaches to Native American affairs that contrast starkly not only with one another, but also with the self‑determination era[174]—the modern era in which the compact’s commitment to equity must be implemented, including in relation to the basin tribes.

Turning initially to the allotment and assimilation era, it began with the 1887 Dawes Act,[175] “civilization and assimilation” being the prevailing theme—one implemented by “legislation providing for the acquisition of Indian lands and resources” and rationalized as serving Native people’s best interests.[176] “Civilization” meant their acculturation to Euro‑American institutions such as Christianity, private property, agriculture, and the English language, while “assimilation” contemplated Native peoples’ adoption of these institutions, as well as privatization of tribally‑held reservation lands and transfer of non‑privatized “surplus” lands into non‑Indian ownership.[177] This policy was a failed social experiment.[178]

With the Meriam Report’s release in 1928,[179] followed by passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in 1934,[180] federal policy shifted. “[N]ew policies were advocated by organizations and individuals who spoke and published their doubts about allotment and assimilation.”[181] Sparking this policy shift, the Meriam Report drew attention to Native peoples’ deplorable living conditions, and “defined the goal of Indian policy as the development of all that is good in Indian culture,” rather than the “crush[ing] out [of] all that is Indian.”[182] The IRA, the era’s “crowning achievement,”[183] set forth this prohibition: “[H]ereafter no land of any Indian reservation, created or set apart by treaty or agreement with the Indians, Act of Congress, Executive order, purchase, or otherwise, shall be allotted in severalty to any Indian.”[184] Allotment ended. Beyond that milestone, the IRA provided for the adoption of tribal constitutions and bylaws (subject to secretarial approval),[185] as well as tribal charters of incorporation (subject to secretarial petition),[186] and although not all tribes favored these measures,[187] the IRA has been hailed as “key to the New Deal’s attempt to encourage economic development, self‑determination, cultural pluralism, and the revival of tribalism.”[188]

Then the policy pendulum swung back with the advent of a new era, “termination,” whose label carries connotations that speak for themselves.[189] Spanning from the mid‑1940s to the early 1960s, this era involved “the most concerted drive against Indian property and Indian survival since the removals following the act of 1830 and the liquidation of tribes and reservations following 1887.”[190] Most notably, the unique, longstanding trust relationship between tribal nations and the United States was put in the crosshairs.[191] “[F]ederal policy dealing with Indian lands and reserves during the termination era focused primarily on ending the trust relationship between the United States and Indian tribes, with the ultimate goal being to subject Indians to state and federal laws on exactly the same terms as other citizens.”[192] To this end, Congress adopted in 1953 House Concurrent Resolution 108—whose policy statement “dominated Indian affairs for most of the next decade”[193]—and enacted subsequent legislation terminating previously federally recognized tribes and bands (e.g., seventy tribes and bands in 1954 alone).[194] As with allotment, the end results for terminated tribes and Native individuals were “tragic,” including cessation of federal trusteeship over landholdings; discontinuation of federal health, welfare, housing, and other social programs; and imposition of state jurisdiction (adjudicatory and legislative) and state taxation.[195]

Far more could be said about these shifts in federal Indian policy surrounding the 1932 to 1951 period during which the Yellowstone River Compact took shape. For present purposes, the takeaway goes back to “equitable division and apportionment,” as that aspirational phrase appears in the compact’s preamble.[196] The “whipsawing”[197] policy eras are an important aspect of the compact’s historical context—or, put differently, how state and federal negotiators (and others) perceived equity, including in relation to Native peoples such as the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne. Such perceptions are reflected in the particular features of the compact’s governance structure and apportionment.

2. Governance Structure: Yellowstone River Compact Commission

Starting with governance, Article III establishes the Yellowstone River Compact Commission for administration of the instrument between Montana and Wyoming, but not North Dakota.[198] This provision lays a foundation for the Commission’s composition, powers and duties, as well as dispute resolution processes.[199]

With respect to composition, the Yellowstone River Compact Commission is a three‑member body.[200] One representative each from Montana and Wyoming are selected by the respective governors and, if requested by the states, one federal representative is selected by the Director of the U.S. Geological Survey.[201] Both state representatives wield voting power, but the federal representative generally lacks it, subject to one exception covered below.[202] If appointed, the federal representative serves as Commission chair.[203] In addition to these representatives, the compact calls for various federal officials (e.g., the Interior Secretary and Secretary of the Army) to cooperate ex officio with the Commission “in the collection, correlation, and publication of records and data necessary for the proper administration of the Compact.”[204]

The term “jurisdiction” is used to refer to the Yellowstone River Compact Commission’s powers and duties.[205] They include “the collection, correlation, and presentation of factual data, the maintenance of records having a bearing upon the administration of [the] Compact, and recommendations to such States upon matters connected with” compact administration.[206] Further, as set forth in a separate provision, the Commission is empowered “to formulate rules and regulations,” including amending them, and “to perform any act which [the Commission] may find necessary to carry out the provisions of [the] Compact.”[207]

The compact also outlines in Article III(F) a dispute resolution process for the Commission and, as alluded to above, the federal representative is positioned, at least per the provision’s text, in a tie‑breaking role.[208] The compact negotiators envisioned situations where the state representatives might not “unanimously agree” on matters “necessary to the proper administration” of the compact.[209] Faced with such impasses, the compact vests the federal representative with a tie‑breaking vote—specifically, the federal representative “shall have the right to vote upon the matters in disagreement,” and “such points of disagreement shall then be decided by a majority vote,” with each representative entitled to one vote.[210]

It is important to highlight that Article III(F)’s dispute resolution provision does not stand alone—in at least two related ways. First, acting under its authority “to formulate rules and regulations” for compact administration,[211] the Yellowstone River Compact Commission in 1995 adopted Rules for the Resolution of Disputes over the Administration of the Yellowstone River Compact.[212] Intended to clarify and flesh out Article III(F)’s text, these dispute resolution rules emphasize “joint problem solving and consensus building,” and generally put into place a three‑phase process consisting of unassisted negotiation,[213] facilitation,[214] and voting.[215] Second, with respect to this process’s voting phase, the federal representative notably adheres to an abstention policy, whereby that official will not cast a tie‑breaking vote on administrative matters about which the state representatives disagree.[216] Tension exists between this policy and the dispute resolution process contemplated by Article III(F)’s text; however, this tension apparently has existed as a governance issue since at least the mid‑1980s.[217]

3. Interstate Apportionment & Tribal Water Rights

Shifting from governance to apportionment, two compact provisions, Articles V and VI, are instrumental in prescribing how the use of water is apportioned across the basin. Both provisions rest on the compact’s definition of “Yellowstone River System”: “the Yellowstone River and all of its tributaries, including springs and swamps, from their sources to the mouth of the Yellowstone River near Buford, North Dakota, except those portions thereof which are within or contribute to the flow of streams within the Yellowstone National Park.”[218]

With the compact’s hydrological scope delineated in this way, Article V establishes a three‑tier apportionment for Montana’s and Wyoming’s portions of the basin upstream of Intake, Montana,[219] excluding from the apportionment domestic uses and certain stock water uses—for example, if the capacity of a stock water reservoir is twenty acre‑feet or less.[220]

Atop the apportionment’s first tier are pre‑1950 appropriative rights. Specifically, as spelled out in Article V(A): “Appropriative rights to the beneficial uses of the water of the Yellowstone River System existing in each signatory State as of January 1, 1950, shall continue to be enjoyed in accordance with the laws governing the acquisition and use of water under the doctrine of appropriation.”[221]

Article V(B), in turn, carves out a second tier consisting of supplemental water supplies for pre‑1950 appropriative rights along the interstate tributaries (Clarks Fork, Bighorn, Tongue, and Powder rivers),[222] stating:

Of the unused and unappropriated waters of the Interstate tributaries of the Yellowstone River as of January 1, 1950, there is allocated to each signatory State such quantity of that water as shall be necessary to provide supplemental water supplies for the rights described in [Article V(A)], such supplemental rights to be acquired and enjoyed in accordance with the laws governing the acquisition and use of water under the doctrine of appropriation.[223]

Following this text, Article V(B) goes on to establish a third tier of post‑1950, percentage‑based rights along the interstate tributaries, providing: “[T]he remainder of the unused and unappropriated water is allocated to each State for storage or direct diversions for beneficial use on new lands or for other purposes” on a percentage basis.[224] The specific splits along each tributary are as follows: Clarks Fork (Montana, 40 percent; Wyoming, 60 percent), Bighorn River (Montana, 20 percent; Wyoming, 80 percent), Tongue River (Montana, 60 percent; Wyoming, 40 percent), and Powder River (Montana, 58 percent; Wyoming, 42 percent).[225]

These allocations notably are not set in stone. Rather, the Yellowstone River Compact Commission is authorized, “[f]rom time to time,” to “re‑examine the allocations . . . and upon unanimous agreement . . . recommend modifications . . . as are fair, just, and equitable.”[226] “Priorities of water rights” are one factor within an inexhaustive list enumerated by the compact for such modifications, alongside “[a]creage irrigated,” “[a]creage irrigable under existing works,” and “[p]otentially irrigable lands.”[227]

While Article V is fairly detailed in mapping out its three‑tier apportionment, Article VI on tribal water rights consists of one sentence: “Nothing contained in this Compact shall be so construed or interpreted as to affect adversely any rights to the use of the waters of [the] Yellowstone River and its tributaries owned by or for Indians, Indian tribes, and their reservations.”[228] This disclaimer is the only compact provision expressly addressing tribal water rights. Viewed in historical context, the U.S. Supreme Court had recognized in its 1908 Winters decision, handed down more than forty years before the compact’s adoption, the existence of an Indian reserved right for the Fort Belknap Reservation in Montana, reasoning that because water was necessary to fulfill the purpose for which the Reservation had been established, a reserved right had been created implicitly upon the Reservation’s creation.[229] The Yellowstone River Compact’s negotiators were certainly familiar with Winters, both in general and as applied to the basin tribes’ reservations.[230] Nonetheless, Article VI’s one‑sentence disclaimer is what was ultimately penned and, as discussed further below,[231] gives rise to competing views on the provision’s interface with Article V.[232]

With this roadmap of the Yellowstone River Compact’s history and features (legal landscape) in mind, it is time to look towards the future. “Equitable division and apportionment” held whatever meaning it did for compact negotiators roughly seventy‑five years ago when they included that phrase (again, norm) in the preamble[233] and designed the governance structure and apportionment in their particular forms. Even more interesting and important, in my view, is to consider what “equitable division and apportionment” should mean, and how the norm could be realized to a greater extent, along the Yellowstone going forward.

III. “Equity” for Whom?

This line of inquiry animates the question posed by this Part’s title. Equity indeed may be in the eye of the beholder, but its subjectivity does not eviscerate its value as a norm for critiquing and suggesting reforms to interstate compacts or other instruments used to mediate co‑sovereign relations over transboundary waters.[234] The discussion below thus begins by delving further into the meaning of “equity” in this context, and then leverages that discussion—specifically, its coverage of two categories of equity, procedural and substantive—to revisit the Yellowstone River Compact’s legal architecture and the previously identified issues of concern amidst the self‑determination era of federal Indian policy. The Yellowstone River Compact Commission’s exclusion of tribal representatives is considered before turning to the unclear and contested status of tribal water rights within (or outside) the compact’s apportionment.

A. “Equity” as a Norm

It is one thing to highlight “equitable division and apportionment” as a fundamental goal in the Yellowstone River Compact’s preamble,[235] or in the various legislation authorizing the compact’s negotiation from 1932 to 1951.[236] It is another thing, however, to consider what exactly is packed into the norm underlying that phrase: equity. How should equity be conceptualized? Bearing not just on the compact, but on the entirety of transboundary water law and policy, this line of inquiry—conceptualization of equity—is critical for figuring out what human relationships over and with transboundary rivers such as the Yellowstone, as well as other water bodies, ought to look like in the future, including how interstate compacts and other water institutions ought to evolve.[237]

The Yellowstone River Compact’s emphasis on equity was not a one‑off—just the opposite—and this fact should be highlighted at the outset. Consider the foundational role played by equity within the broad and crucial field of international water law—specifically, the norm enshrined in the 1997 U.N. Watercourses Convention, “equitable and reasonable utilization and participation,”[238] recognized as customary law by the International Court of Justice.[239] That norm’s genesis at the international level, in turn, traces to the U.S. Supreme Court’s equity‑driven jurisprudence, amassing since the early twentieth century, addressing state sovereigns’ legal relations along interstate rivers—the Court’s equitable apportionment doctrine.[240] Wyoming v. Colorado is, again, one notable precedent within this jurisprudence[241] and, as mentioned earlier,[242] Delph Carpenter’s formative experience with that litigation forever shaped his views on alternative instruments for achieving equitable apportionment—interstate water compacts—in lieu of pursuing decrees from the Court.[243]

Beyond equity’s prevalence as a norm within transboundary water law and policy, what is even more critical for present purposes concerns how the norm is analyzed, at both the domestic and international levels. The frameworks run parallel. Announced in its 1945 Nebraska v. Wyoming decision, the U.S. Supreme Court has developed a multi‑factor framework for analyzing equitable apportionment, explaining that “apportionment calls for the exercise of an informed judgment on a consideration of many factors” (a “delicate adjustment of interests”), and clarifying that the factors enumerated within the framework “are merely an illustrative, not an exhaustive catalogue.”[244] This approach closely resembles that later adopted in the 1997 U.N. Watercourses Convention, which similarly contains an inexhaustive list of factors, without assigned relative weight, “all of which are to be considered together and a conclusion reached on the basis of the whole.”[245]

At least two takeaways should be gleaned from these analyses. First, equity is a context‑specific norm for transboundary waters. To devise an “equitable” apportionment along a given river (or other water body), the totality of the circumstances must be taken into account.[246] Second, as a corollary, time is an important dimension of this contextuality. As the context surrounding transboundary waters inevitably changes over time, a gap may widen between what equity seems to call for in the present versus what it was perceived to call for in the past, such as when an interstate compact was drafted espousing the goal of “equitable” apportionment.[247]

Beyond being context‑specific and pervasive in transboundary water law and policy, equity is also a norm encompassing two broad categories reflected in the phrase “equitable and reasonable utilization and participation”[248] from the 1997 U.N. Watercourses Convention: substantive equity and procedural equity.[249] To reiterate, equity is a synonym for fairness.[250] When thinking about the fairness of transboundary water institutions such as interstate compacts, one logical focus is the substance of an apportionment. For example, which types of parties are allocated water, what is the order of priority during shortages, how secure are different types of water rights, and so forth?[251] These questions capture what is referred to as “substantive equity” and associated principles such as reciprocity, fidelity, reliability, and flexibility.[252] In addition, a complementary angle for evaluating the fairness of transboundary water institutions is to consider the composition and processes of their governance structures. For example, which parties have a voice in decision‑making and which do not, how transparent are decision‑making processes, how effective is the particular structure in actually enabling governance, and so on?[253] These related questions reflect the essence of what has been called “procedural equity,” which involves principles such as inclusivity, diligence, and transparency.[254]

While there is no singular way of thinking about what the norm of equity means in transboundary water law and policy, the material above lays the foundation for my approach with regard to the Yellowstone River Compact. In its current form, nearly seventy‑five years after its genesis, the compact raises significant issues of procedural and substantive equity involving the basin tribes and their water rights. The existence of these issues, respectfully, throws into question whether the compact’s commitment to “equitable division and apportionment”[255] is just words on a page. For my part, I would like it to be more.

B. Reimagining “Equitable Division & Apportionment”

How exactly the Yellowstone River Compact might evolve to become more equitable is a topic that should be approached with humility and respect, especially insofar as the advocacy is intended to offer ideas to Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne tribal leaders and members. That is the spirit in which the pages below have been written. After putting the advocacy into context by discussing key features of the self‑determination era—the current era of federal Indian policy as noted earlier—the discussion turns to the equity‑related issues just alluded to. Regarding procedural equity, my overall prescription is that the Yellowstone River Compact Commission should be reconstituted in an updated form to allow for direct representation of each basin tribe, if so desired by the tribe. As for substantive equity, I advocate for the formation of a consensus‑based agreement that clarifies the status of, and ultimately protects, tribal water rights under the compact’s apportionment.

1. Federal Indian Policy: Self‑Determination Era

In modern times, the Yellowstone River Compact exists amidst the self‑determination era of federal Indian policy, which commenced during the 1960s.[256] With the allotment and assimilation era, as well as the termination era, having run their course, it is this distinct period in which the Yellowstone River Compact Commission is administering the instrument, including its provisions addressing the interstate apportionment and the basin tribes’ water rights.[257] As the U.S. Supreme Court has described, a congressionally approved compact is both an interstate contract and a federal statute.[258] It is, by definition, federal law. As such, however the Yellowstone River Compact’s laudable goal of “equitable division and apportionment”[259] is approached and hopefully realized in coming years, it should be in ways that comport with and further, not undermine, the self‑determination era’s key priorities.

A bit more should be said about the current era and those priorities. The Yellowstone River Compact had been in existence for about a decade before the proverbial pendulum of federal Indian policy swung away from the termination era and into the self‑determination era—an era marking “a return to much of the basic philosophy and many of the policy objectives rooted in the Indian reorganization era.”[260] As used in this context, “[s]elf‑determination” has been described as constituting “the strongest expression of [c]ongressional and [e]xecutive branch support for the development of tribal governments, reservation economies, and Indian people, as well as recognition of the importance of tribal sovereignty.”[261]

These defining priorities of the self‑determination era—respect for tribal self‑governance, sovereignty, and self‑determination—can be gleaned from numerous pieces of legislation and executive documents that have emerged since the 1960s, including President Nixon’s landmark message to Congress on July 8, 1970.[262] Calling for congressional renunciation, repudiation, and repeal of termination policy, Nixon acknowledged that “cultural pluralism is a source of national strength,”[263] and advocated in pathbreaking ways for tribal self‑governance. Specifically, he called for tribal sovereigns, if they desired, to be empowered to assume control and responsibility over federal programs historically administered on reservations by federal agencies.[264] Nixon referenced federally funded and administered programs within the Department of the Interior and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, expressly singling out tribal sovereigns’ control over their own schools.[265]

Fast‑forwarding more than a half‑century, President Biden issued an executive order in 2023 echoing much of what President Nixon had said to Congress in 1970.[266] This order’s policy section could be paraphrased but, in my view, deserves to be excerpted:

My Administration is committed to protecting and supporting Tribal sovereignty and self‑determination, and to honoring our trust and treaty obligations to Tribal Nations. We recognize the right of Tribal Nations to self‑determination, and that Federal support for Tribal self‑determination has been the most effective policy for the economic growth of Tribal Nations and the economic well‑being of Tribal citizens. Federal policies of past eras, including termination, relocation, and assimilation, collectively represented attacks on Tribal sovereignty and did lasting damage to Tribal communities, Tribal economies, and the institutions of Tribal governance. By contrast, the self‑determination policies of the last 50 years—whereby the Federal Government has worked with Tribal Nations to promote and support Tribal self‑governance and the growth of Tribal institutions—have revitalized Tribal economies, rebuilt Tribal governments, and begun to heal the relationship between Tribal Nations and the United States.

* * *

Now is the time to build upon this foundation by ushering in the next era of self‑determination policies and our unique Nation‑to‑Nation relationships, during which we will better acknowledge and engage with Tribal Nations as respected and vital self‑governing sovereigns. As we continue to support Tribal Nations, we must respect their sovereignty by better ensuring that they are able to make their own decisions about where and how to meet the needs of their communities. No less than for any other sovereign, Tribal self‑governance is about the fundamental right of a people to determine their own destiny and to prosper and flourish on their own terms.[267]

This text vividly captures the self‑determination era’s distinct character.

That said, one aspect of the current era not emphasized enough up to this point appeared in the Biden Administration’s commitment “to honoring our trust . . . obligations to Tribal Nations.”[268] This commitment grew out of the trust relationship shared by the U.S. and tribal sovereigns ever since our nation‑state’s founding.[269] Rooted in promises of protection made by the U.S. to tribal nations, explicitly or implicitly, in treaties and treaty substitutes,[270] the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1832 Worcester v. Georgia decision is the foundational precedent recognizing and articulating the protectorate theory for the trust relationship.[271] Chief Justice John Marshall anchored it in the law of nations.[272] All told, rather than rationalizing its termination, federal Indian policy during the self‑determination era calls for what President Biden’s executive order recommitted the U.S. to: honoring and fulfilling the trust relationship. It applied horizontally across the entire federal government,[273] adhering to all agencies’ activities, as well as to congressional legislation.[274]

Further grounding it in this discussion, the trust relationship bears directly on Tribal water rights such as those held by the U.S. on behalf of the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne.[275] The manual of the Department of the Interior, which encompasses the Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and U.S. Geological Survey, sets forth principles for managing Indian trust assets, including Tribal water rights,[276] providing: “The proper discharge of the Secretary’s trust responsibilities requires that persons who manage Indian trust assets . . . [p]rotect and preserve Indian trust assets from loss, damage, unlawful alienation, waste, and depletion . . . [and] [p]romote tribal control and self‑determination over tribal trust lands and resources.”[277] Similarly, the manual includes this policy statement:

It is the policy of the Department of the Interior to recognize and fulfill its legal obligations to identify, protect, and conserve the trust resources of federally recognized Indian tribes and tribal members, and to consult with tribes on a government‑to‑government basis whenever plans or actions affect tribal trust resources, trust assets, or tribal health and safety.[278]

“Tribal Policy Principles” adopted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also incorporate the trust relationship, stating the agency “will work to meet trust obligations, protect trust resources, and obtain tribal views of trust and treaty responsibilities or actions related to the Corps.”[279]

In sum, as advocated at the beginning of this discussion of the self‑determination era, the Yellowstone River Compact’s goal of “equitable division and apportionment”[280] should be pursued in modern times to achieve the era’s core policy priorities, including respecting tribal self‑governance, sovereignty, and self‑determination, as well as honoring the trust relationship. This advocacy applies in equal measure to procedural equity and substantive equity.

2. Inclusive Co‑Sovereign Governance

Looking more closely at procedural equity, if the Yellowstone River Compact truly aims to bring about “equitable division and apportionment”[281] along the river system here in the self‑determination era, the current treatment of basin tribes under the compact’s governance structure needs to be reconsidered. More specifically, the Yellowstone River Compact Commission’s composition and processes should be updated to acknowledge the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne for what they are—tribal sovereigns—and to include them in governance alongside their co‑sovereigns, the basin states and the United States, if that is something each respective tribe would be interested in.[282]

In support of this general proposal, a few points are offered for consideration.

First, there is no dispute regarding the tribal nations’ presence within the Yellowstone River Basin, or the existence and status of their water rights as Indian trust assets. Occupying reservations established prior to Montana’s and Wyoming’s statehood as noted earlier,[283] the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne are federally recognized tribes that maintain their own governments and actively engage in self‑determination.[284] They are, indeed, sovereigns—and indisputably share a trust relationship with the United States.[285] Further, this trust relationship extends to the tribes’ water rights. The pathways through which each tribe has secured recognition and quantification of its water rights within the colonial (U.S.) legal system admittedly differ. The Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho navigated Wyoming’s Big Horn general stream adjudication,[286] while the Crow and Northern Cheyenne formed state‑tribal compacts ratified by Congress, the Montana legislature, and the respective tribes.[287] Nonetheless, across the board, the same takeaway applies: the United States holds the water rights of each basin tribe as a trustee.

Second, as covered at length above,[288] the river system along which the tribal nations are situated and to which their water rights pertain, the Yellowstone, is not the same river system for which the compact was drafted. It plainly has changed since 1950. No one holds a crystal ball to foretell exactly what will happen further into the twenty‑first century with variables such as temperature increase, decreased snowpack and increased rainfall, longer growing seasons, heightened evaporation and evapotranspiration, seasonality and timing of runoff, and so forth.[289]

What is clear right now, however, is that climate change is happening along the Yellowstone River system, and a host of challenging water management issues face the basin in coming years. Recall this encapsulation for runoff: “An overwhelming preponderance of scientific evidence shows that the future envelope of streamflow variability will differ from the historical. . . . [S]treamflow is likely to change, in amount, timing and distribution.”[290] Recall, too, Crow elders’ firsthand observations of weather pattern and ecosystem changes: “far less snowfall and milder winters, increased spring flooding, hotter summers,” and “extreme, unusual, and unpredictable weather events, compared to earlier times when seasons were consistent year after year.”[291] The bottom line is that these myriad changes will impact the basin tribes’ water rights, just as they will do so for appropriative rights held by water users in Montana and Wyoming,[292] as well as for water rights held by the United States for public lands throughout the basin.[293]

Third, the Crow, Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne lack direct representation on the Yellowstone River Compact Commission, and indirect federal representation is not an adequate substitute. As outlined earlier, the state sovereigns, Montana and Wyoming, each have one representative on the Commission, and the United States also is afforded one representative, if requested by the states, to be appointed by the Director of the U.S. Geological Survey.[294] This structure excludes the basin tribes as co‑sovereigns, despite their long‑existent reservations and clearly established water rights as Indian trust assets.[295] Further, as mentioned above, the federal representative can only vote on administrative matters if there is a tie vote deadlocking the state representatives during dispute resolution,[296] and for several decades the federal representative has followed an abstention policy and refused to cast any tie‑breaking vote despite the compact’s text on this subject.[297] Also notable with respect to the federal representative are the wide‑ranging, potentially conflicting interests of the diverse federal agencies throughout the basin, which not only encompass the federal trustee’s responsibilities towards the basin tribes, but also touch on water infrastructure operations and associated obligations of the Bureau of Reclamation and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.[298] For these reasons and others, it would be inequitable for the basin tribes to be relegated to indirect representation by the federal commissioner.

With the preceding considerations in mind, the essential challenge of realizing procedural equity by updating the Yellowstone River Compact Commission to include the basin tribes is seemingly basic: How? As used here, “how” refers to two broad topics: (1) how might an updated Commission be composed, and (2) how might this new structure be brought into being. My initial input on both topics is deferential, not out of intellectual laziness, but because of the importance of humility and respect in this space. It should be left to the basin’s co‑sovereigns themselves, in my view, to design a new structure for co‑sovereign governance along the Yellowstone—both the ultimate design itself as well as the decision‑making process (including optimal instrument) for creating it. Having said that, the discussion below offers food for thought on each topic, all for the co‑sovereigns to take or leave.