Open PDF in Browser: Jonathon J. Booth,* Policing After Slavery: Race, Crime, and Resistance in Atlanta

This Article places the birth and growth of the Atlanta police in context by exploring the full scope of Atlanta’s criminal legal system during the four decades after the end of slavery. To do so, it analyzes the connections Atlantans made between race and crime, the adjudication and punishment of minor offenses, and the variety of Black protests against the criminal legal system. This Article is based, in part, on a variety of archival sources, including decades of arrest and prosecution data that, for the first time, allow for a quantitative assessment of the impact of the new system of policing on Atlanta’s residents.

This Article breaks new ground in four ways. First, it demonstrates that rather than simply maintaining the social relations of slavery, Atlanta’s police force responded to the challenges of freedom: it was designed to maintain White supremacy in an urban space in which residents, theoretically, had equal rights. Second, it shows that White citizens’ beliefs about the causes of crime and the connections between race and crime, which I call “lay criminology,” influenced policing strategies. Third, it adds a new layer to our understanding of the history of order-maintenance policing by showing that mass criminalization for minor offenses such as disorderly conduct began soon after emancipation. This type of policing caused a variety of harms to the city’s Black residents, forcing thousands each year to pay fines or labor for weeks on the chain gang. Fourth, it shows that the complaints of biased and brutal policing that animate contemporary police reform activism have been present for a century and a half. In the decades after emancipation, Atlanta’s Black residents, across class lines, protested the racist criminal legal system and police abuses, while envisioning a more equitable city where improved social conditions would reduce crime.

Introduction

Atlanta, Georgia, is currently embroiled in a years-long struggle over the construction of a massive police training facility.[1] The facility is being built on forested land that once housed the Atlanta Prison Farm, where for several decades prisoners were forced to grow food and raise animals for the profit of the prison system.[2] Opponents of the project, who call the facility “Cop City,” argue that it will further entrench the pattern of racist and brutal policing that has characterized law enforcement in Atlanta for decades. An occupation of the forest and widespread protests against the facility have led to domestic terrorism charges against dozens of protestors, the arrest of bail-fund organizers on felony fraud charges, and the death of one activist, who was shot fifty-seven times by the police.[3]

In August 2023, Georgia’s Attorney General charged sixty-one anti-Cop City activists[4] under the state’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) statute.[5] The one‑hundred-page indictment alleges that the indicted activists conspired to prevent the police training center from being built—but fails to identify a specific illegal enterprise.[6] The indictment characterizes the protestors as motivated by anarchist ideology and states that they seek to promote ideas such as “collectivism, mutualism/mutual aid, and social solidarity.”[7] Among the alleged overt acts in furtherance of the conspiracy are camping in the forest,[8] a transfer of $61.21 for “forest kitchen materials,”[9] and one defendant signing his name as “ACAB.”[10] Many of the indicted activists are not accused of participating in any illegal activity other than their involvement in the broader alleged conspiracy. As part of its lengthy analysis of the protestors’ ideology, the indictment states, “[o]ne of the most common false narratives promoted by Defend the Atlanta Forest is that of police aggression.”[11]

This Article shows that after the destruction wrought by the Civil War, Atlanta’s White powerbrokers hoped to transform their city into a regional leader. They believed that economic growth required a modern police force to control the crime and disorder they associated with the city’s burgeoning Black population. The racism and brutality at the heart of contemporary protestors’ critiques of the Atlanta Police Department, I argue, have been features of policing in the city since the department’s creation 150 years ago in 1874.[12] Once the department was created, Atlanta’s police used their discretion to arrest Black Atlantans disproportionately for vague, petty offenses. Obtaining convictions for those petty offenses was easy because the city’s Recorder’s Court, where minor offenders were tried, lacked due process protections.[13] The high case load and lack of procedural protections made it extremely difficult for the accused to prove their innocence against the word of an officer.[14] Those convicted were assessed onerous fines. If they could not pay, they were forced to work off the fines on the chain gang, building Atlanta’s streets while wearing striped prison uniforms.[15] Whether it acquired revenue or free labor, the city benefitted tangibly from these minor convictions and its leaders had no interest in reforming its criminal legal system. Consequently, Black Atlantans have protested the city’s criminal legal system[16] since the first years after the Civil War, and that legacy of protest continues to this day.[17]

This Article places the birth and growth of the Atlanta police in context by exploring the full scope of Atlanta’s criminal legal system in the decades between the end of the Civil War and the first decade of the twentieth century.[18] In so doing, this Article analyzes the connections Atlantans made between race and crime, the adjudication and punishment of minor offenses, and the variety of Black protests against the criminal legal system. This Article is based in part on a variety of archival sources, including decades of arrest and prosecution data that, for the first time, allow for a quantitative assessment of the impact of the system of policing inaugurated in 1874 on Atlanta’s residents.[19] These statistics not only reveal the extraordinary growth in the number of arrests in the decades after the formation of the police force—leading Atlanta to have the highest arrest rate in the country by the turn of the twentieth century—but also demonstrate that Atlanta was an early adopter of mass order-maintenance criminalization.[20] In 1902, for example, 83 percent of all arrests were for the petty order-maintenance offenses of disorderly conduct, drunkenness, or idleness.[21]

The historical literature on policing has developed largely independently of related legal scholarship. This Article bridges the gap between the two by investigating the central research questions of the legal scholarship through the lens of the historical literature and using historical sources. It breaks new ground in four ways.

First, this Article demonstrates that the Atlanta Police Department was a new institution that developed in response to post-slavery conditions: It was designed to proactively make mass arrests for minor offenses and to maintain White supremacy in a rapidly growing city in which residents, theoretically, had equal rights.[22] This Article disrupts simplistic, monocausal narratives of police development by explaining why Atlanta’s police history does not fit neatly into established categories. Atlanta’s force was not directly copied from England or Northern cities; unlike those police forces, it was not designed primarily to prevent riots and crime.[23] Nor was it a corrupt organization staffed by lazy and incompetent officers more concerned with collecting a paycheck than making arrests.[24] Nor was Atlanta’s police force a direct descendant of the pre-war slave patrol system, where many scholars have located the origins of Southern police forces.[25]

A key reason why the history of Atlanta’s police does not fit well into existing categories is that most policing scholarship focuses on Northern cities in the second half of the twentieth century.[26] This vital work has clearly demonstrated the centrality of resource extraction and racialized social control to policing in recent decades, but it does not explore the origins of these characteristics. In addition, there are a handful of works that focus on policing in the antebellum South. These works demonstrate that antebellum Southern police forces served to control diverse urban populations including free people of color and immigrants, along with enslaved people.[27] Little research, however, examines the numerous Southern cities that created police forces only after emancipation.[28] This Article begins to fill that gap and demonstrates that Atlanta’s new police force had the same goal as police forces in other cities, Southern and Northern: enforcing racialized social control on a free, urban population.

Second, this Article shows that White citizens’ beliefs about the causes of crime and the connections between race and crime, which I call “lay criminology,”[29] influenced policing strategies. Scholars have long recognized that popular perceptions about the causes of crime and the relationship between race and crime are spread and shaped by the media[30] and that these perceptions have an important effect on police policy and tactics.[31] No scholarship, however, has addressed the relationship between popular criminological ideas and police practices in the post-emancipation South. This Article demonstrates that Atlanta’s newspapers promoted lay criminological ideas that connected crime to Black leisure and family life. More directly, newspapers also demanded that the police force take action against Black leisure by raiding saloons and dancehalls.[32] The police responded by making an enormous number of arrests in such raids.

Third, this Article analyzes how minor offenses were policed and prosecuted in Atlanta. It adds a new layer to our understanding of the history of order-maintenance policing by showing that mass criminalization of minor offenses began soon after emancipation as a response to the urbanization of Georgia’s Black population. This type of policing caused a variety of harms to the city’s Black residents, including forcing thousands each year to pay fines or labor for weeks on the chain gang.[33] Recent scholarship has demonstrated the importance of low-level arrests in enforcing White supremacy and social control today,[34] especially when the arrests result from a strategy of order-maintenance policing, which expanded rapidly in the “broken windows” era of the 1990s.[35] This Article argues that social control through mass arrests for minor offenses is a constitutive element of the modern American criminal legal system and dates to the system’s earliest days.

In addition, this Article provides a historical dimension to the growing literature on misdemeanor enforcement in low-level courts. It does so by examining the unfairness of Atlanta’s Recorder’s Court, which adjudicated offenses against city ordinances. The literature on low-level courts emphasizes that such courts have few procedural protections and are characterized by discretion, informality, rapid adjudication, and social control.[36] In the aftermath of the Department of Justice’s 2015 report on policing and misdemeanor adjudication in Ferguson, Missouri,[37] scholars have also examined the economic and social impact of the fines and fees that result from low-level interactions with the criminal legal system.[38] This Article demonstrates that the conclusions of this literature are part of a broader pattern that dates back to the nineteenth century, where the Recorder’s Court generated large amounts of revenue in fines and inflicted a wide variety of harm on the city’s Black residents.

Fourth, this Article shows that the complaints of biased and brutal policing that motivate contemporary police reform activists, including those protesting the construction of Cop City, have been present for a century and a half.[39] A proper understanding of this history has never been more urgent. Over the past decade, in Atlanta and around the country, powerful movements have challenged the power of police and highlighted the ongoing toll of police discrimination and violence. This Article shows that, as far back as the 1860s, Atlanta’s Black residents, across class lines, protested the criminal legal system and police abuses while envisioning a more equitable city where improved social conditions would reduce crime.[40]

By placing Black protest at the center of the history of policing, this Article highlights the historical foundation upon which the recent legal literature on policing and social movements builds. Until recently, much of the legal scholarship examined the questions arising out of the post-civil rights movement Constitution: how police can avoid abuse of power, achieve legitimacy, and support procedural justice.[41] In recent years, inspired in part by the Black Lives Matter movement, some scholars have moved away from these themes to fundamentally critique policing itself.[42] Scholarship in this vein has called to democratize, disband, disaggregate, reimagine, or abolish police.[43] This critical scholarship has justified its call to make fundamental changes to policing by focusing on the physical and financial harm that policing does to subordinated communities.[44] This Article demonstrates that the harm of policing reaches back at least to the mid-nineteenth century. In addition to inspiring more fundamental critiques of policing, the Black Lives Matter movement has also led legal scholars to focus on the importance of social movements to criminal law.[45] Yet the history of Black protest is underdeveloped, especially protest of the criminal legal system between the end of Reconstruction and the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909.[46] This Article shows that the centrality of the criminal legal system to Black protest is part of a long tradition and has shaped American criminal justice institutions since emancipation.

In sum, this Article demonstrates that the new system of policing that developed in Atlanta after the Civil War supported White supremacy and spurred strong resistance from Black residents of the city. Racially biased low-level enforcement has been a part of American policing since the end of slavery. The Article proceeds as follows: Part I describes Atlanta’s pre-police law enforcement system and shows how that system developed into the modern police force created in 1874. Part II surveys the lay criminological beliefs of Atlanta’s leaders, illuminating how most White Atlantans connected Blackness to crime and believed that Black leisure activities were an important driver of criminality. Part III examines the practices of policing and prosecuting Black Atlantans and demonstrates that the vast majority were arrested for minor violations, such as disorderly conduct, and faced trial in the Recorder’s Court with little due process. Part IV explores the variety of Black protests against the criminal legal system, including the Black middle class’s attempts to create an alternate criminology focused on improving social conditions and the Black working class’s more direct resistance to the police. Part V examines the lessons that this history holds for our contemporary understanding of policing.

I. The Death of Slavery and the Birth of the Atlanta Police

“South of the North, yet north of the South,”[47] Atlanta is an important location to study the development of policing after the Civil War and the transformation of pre-war law enforcement institutions into a modern police force.[48] Today, Atlanta is at the epicenter of one of the most highly visible conflicts about the future of policing in the United States.[49] Before the Civil War, however, Atlanta was little more than a village—a village which was burned to the ground by General William Tecumseh Sherman and his army in 1864. In the decades following the war, Atlanta rapidly transformed from a burnt village to the “Gate City” of the South. By 1868, a teacher would write that Atlanta had become “like a star beaming in every direction, and will be in not many years the first after New York and New Orleans.”[50] That year, Atlanta became the state capital; by 1880, it had surpassed Savannah to become the state’s most populous city.[51] The city also boasted a vibrant press, including several Black‑owned newspapers, that reported constantly on crime and policing. During this time of rapid growth, its criminal justice institutions were rebuilt largely from scratch. The new city therefore served as a crucible for, and reflection of, new ideas about crime and policing that developed in response to the challenges of the post-emancipation moment.[52]

Chief among the challenges that Atlanta’s leaders faced was governing a rapidly growing and diversifying city. Most of Atlanta’s residents, Black and White, had moved to the city from elsewhere in the state, and the Black share of the city’s population grew particularly rapidly. Between the 1870s and 1960s, slightly over 40 percent of the city’s residents were Black.[53] The vast majority of Black men and women were employed, but their work was almost always low-paid and intermittent. Scholars have estimated that between 93 and 97 percent of Black residents of Atlanta worked in some form of manual labor, with almost no chance at upward mobility.[54] For about three-quarters of Black men this meant working as unskilled or semi-skilled day laborers, while nearly all employed Black women worked in domestic service.[55] The small Black leadership class consisted primarily of pastors and other professionals, businessmen, and the educators associated with the city’s Black universities.[56]

Atlanta’s rapid population growth belied its underdevelopment. In 1880, just three percent of Atlanta’s streets were paved with broken stone, the remaining 97 percent were dirt.[57] Nevertheless, Atlanta’s boosters were anxious to transform it into an orderly, modern metropolis and the leading city of the New South. Atlanta’s leaders sought to attract business and grow the city by using the police to keep the city’s Black population under control and using chain gang labor to pave and expand roads.[58] By 1900 the growth project had succeeded: Atlanta was the second largest city in the former Confederacy and hosted national events, such as the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition where Booker T. Washington delivered his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech.[59]

Consequently, the Atlanta Police Department’s development was closely tied to the city’s growth and modernization. An 1898 history of the department claimed “[t]o write a history of the Police Department of Atlanta is to give a true picture of its march from an obscure hamlet to a citadel of commercial greatness, its triumph over the devastations of war and its rise from the ashes of desolation to the pyramid of eternal prosperity.”[60] Yet the scholarly analysis of Atlanta’s and other Southern police forces in the nineteenth century is minimal.[61] This Part examines the creation of Atlanta’s police force and demonstrates that it developed to maintain White supremacy in the new circumstances created by the abolition of slavery.[62] The lack of scholarly literature on police forces in other Southern cities in the decades after slavery makes comparison difficult, but it is clear that throughout the region, police forces disproportionately arrested Black residents for minor crimes. Atlanta’s arrest rate was significantly higher than that of other cities. But this is a difference of degree, not of kind, caused largely by Atlanta’s strong focus on growth and modernization.

In the first decade after emancipation, Atlanta haltingly modernized its police force, a widespread process in the nineteenth century. Historians of Anglo-American policing have identified a major transition point in the early nineteenth century when older systems of urban law enforcement, in which constables and watchmen performed a wide variety of tasks, were replaced with the “modern” police force which persists in easily recognizable form to this day.[63] The key moment in this shift is typically identified as the creation of London’s Metropolitan Police force in 1829.[64] Scholars agree that there are four key features that define the police forces that first emerged in the nineteenth century. First, they are characterized by a centralized, hierarchical structure, with a police chief at the top.[65] Second, they are housed in the executive branch of local government rather than the judicial branch, giving mayors and city councils control over the operation of the police force.[66] Third, officers wear uniforms, making them highly visible to the public.[67] Finally, modern police actively patrol, rather than simply responding to reports of crimes; to encourage proactive patrolling, officers are paid salaries rather than fees for each arrest.[68] In addition, in the United States, policemen were usually armed with handguns.[69]

Although night watchmen and constables had long existed, the idea of a salaried, uniformed force that patrolled day and night and could arrest lawbreakers on sight without a warrant represented a new way for the state to enforce the law in urban areas.[70] The police forces of the nineteenth century increased the frequency of interactions between police and citizens, making the threat of arrest and violence much more immediate.[71] In Atlanta, this Section shows, a modern police force was created between 1866 and 1873.

A. Law Enforcement Before the Modern Police Force

Atlanta entered the post-Civil War period without a modern police force. Before the Civil War, Atlanta, like most of Georgia’s towns, had an antiquated system of law enforcement in which a town marshal and a small number of deputies served to keep the peace and perform other diverse duties.[72] This system, notably, was entirely separate from the Fulton County slave patrol.[73]

On January 3, 1866, newly elected mayor James E. Williams gave his inaugural speech to the city council.[74] The “suppression of crime . . . especially such as may be attributable to the changed station of the negro” was at the top of his agenda.[75] He argued that without slavery, local government would have to take on the role of the plantation and police and punish Black Georgians.[76] “To this end,” he concluded, “it will be our highest duty—to have a police of the greatest possible efficiency. Upon this more than else depends the security of our persons and property the good name and prosperity of our city.”[77] It would take eight years for Atlanta to create the police force that Williams desired.

Williams hoped the future of the police would be quite different from its state when he spoke. In 1866, the city’s law enforcement consisted of the city marshal who employed twenty ununiformed “privates.” The privates were paid at most fifty dollars per month but did not necessarily work full time.[78] Over the next seven years, Atlanta’s leaders attempted to reform this archaic system to meet the needs of the city’s growing population and, particularly, to police its growing Black population.[79]

Three aspects of Atlanta’s proto-police set it apart from the force that would be created in 1874. First, Atlanta’s privates received a fee of one dollar per arrest in addition to their salaries.[80] Second, they were selected by the city council, rather than hired through a neutral civil service process; jobs with the city marshal were therefore patronage positions, making the force a key issue in local politics.[81] Third, they wore civilian clothes rather than uniforms.[82] These conditions were not ideal. As one newspaper noted in 1871, Atlanta’s officers “receive a dollar for every offender they arrest, wear citizens’ clothes, and are poorly paid, which, considering that Atlanta is the chief city of the South, is not flattering.”[83] Further, it appears that Atlanta’s “privates” did not take their duties particularly seriously. Numerous instances of drunkenness marred the force, and in the absence of an internal discipline process misbehaving officers faced trial before the Atlanta City Council.[84]

These difficulties caused the city council to twice enact new regulations for the force before fully reorganizing it in 1874. In mid-1867, the city council replaced the ordinances that defined the duties of the chief marshal with a thirty-five-section set of regulations. The new ordinance eliminated many outmoded duties of the chief marshal, such as licensing peddlers and managing weights and measures, and created new rules that represented a first step toward a modern police force.[85] The rank-and-file officers—called policemen rather than privates for the first time—were instructed to keep the peace vigilantly and arrest all offenders who violated the city’s laws. The policemen, however, were still required to perform a variety of other duties, including lighting and extinguishing its streetlamps and guarding the city from fire. Most importantly, the new rules did not change the most archaic aspects of the force: policemen would continue to be elected by the Council, wear civilian clothes, and receive fees for various duties, including arrests.[86]

In 1869, the city council created a stricter set of rules to govern a force that now employed forty-five officers. These rules instituted twice-weekly drills, banned arrest fees, and forbade officers from entering saloons.[87] Despite these changes, the force was still ununiformed and controlled directly by the mayor and council. In fact, Atlanta’s police would not be uniformed until an 1870 state law required it.[88]

Although significant steps toward a modern police force were taken in the second half of the 1860s, Atlanta’s police force remained archaic, and the city’s leaders believed it insufficient for the rapidly expanding city. The Black share of Atlanta’s population more than doubled between 1860 and 1870, from 20 percent to 46 percent, and the city’s White political leadership consequently began to press for a more effective police force with more urgency.[89]

B. Creating a Modern Police Force

Atlanta’s rapid growth convinced the city’s leaders that its archaic police force was plainly insufficient to control the city’s population and prevent crime and disorder.[90] After the city had spent almost a decade trying to improve its police system with minor reforms, the state government granted Atlanta a new charter in 1874 that created the police force that governs Atlanta to this day.[91] This new organization was equipped to grow alongside the city and respond to the incipient racialized understanding of urban crime, which is discussed in depth in Part II.

The new charter created a seven-member Board of Commissioners of Police. The mayor occupied one of the board’s seats and the other six members were elected by the city council for three-year terms.[92] The Board was given “full direction and control of officers and members of the police force,” which included the authority to hire, arm, and uniform as many officers as the city council budgeted for.[93] The Charter gave the chief of police full authority over the force.[94] In addition, it was the board, not the city council, that could discipline misbehaving officers and suspend or remove them from the force.[95] This structure gave the chief of police and board of commissioners a level of independence from the mayor and insulation from electoral politics. Police independence helped to reduce the use of patronage to hire officers and thus stabilized the police force’s personnel.[96]

The Charter’s provisions were supplemented by city ordinances that provided more detailed rules for the force. Officers, for example, were required to “devote their whole time and attention” to policing and were forbidden from holding outside employment and from entering a saloon, even while off duty.[97] Officers were required to become familiar with all the people on their beats, paying particular attention to saloons and gambling houses, and report suspicious persons to their commanding officer.[98] Officers were also empowered to make arrests on the complaint of any citizen without a warrant.[99] The changes were quickly implemented. One newspaper celebrated the fact that officers now were now required to patrol actively and “put under the strictest of military discipline, and must bear himself like a soldier in arms.”[100] A key goal of this well-disciplined force was, in the words of the police chief, to prevent the crime that was “necessarily [a] frequent occurrence, while our city is crowded with idle profligate negroes.”[101]

In contrast to the poor compensation of the privates who made only $600 per year plus fees, the city council set a relatively high initial pay rate for the new policemen. The chief of police would receive a substantial salary of $2,000 per year, while the sergeants would receive $1,820, lieutenants would receive $1,400, and detectives would receive $900.[102] The force’s thirty patrol officers were paid $730 per year.[103] The new officers included former farmers, clerks, railroaders, mechanics, and even a florist.[104]

The patrol officers were required to walk their beats alone and have minimal contact with other policemen, except as needed to carry out their duties.[105] Policemen patrolled the city’s diverse neighborhoods largely on foot. For much of the period before a three-shift system was introduced in 1896, the men worked twelve-hour shifts, walking beats an average of six miles long in the heat and the rain, up and down Atlanta’s hills.[106] A few of the higher-ranking officers had horses, but the department was defined by the solitary officer with a baton and a gun.[107] Although the regulations did not require that officers be a particular race, the force employed only White officers until 1948.[108]

The new police functioned to the satisfaction of the city’s leaders and no major changes to the force’s organization were made in the following three decades, though the number of officers grew. In 1890, the force employed 118 officers.[109] Ninety-six of those were patrol officers who served under six sergeants[110] and three captains.[111] There were also four officers who were detailed as detectives,[112] and others in supplementary positions.[113]

The new structure also allowed for the easy incorporation of new technologies. In the 1890s the department adopted both bicycles and electronic alarm systems, which transformed policing in the city. Bicycles allowed officers to swiftly traverse the city and were much cheaper to maintain than horses. Policemen thus used bicycles to patrol and to dispatch rapidly to reported incidents.[114] In 1897, the force listed eight men as “bicycle officers,” and by 1900 the department owned eighteen bicycles.[115] In 1901, bicycle officers responded to 9,451 “quick calls.”[116] The police chief claimed that bicycles allowed the police to respond quickly to reports of disorder and thus arrest many lawbreakers who would have escaped from foot patrolmen.[117]

Electronic alarm systems similarly enabled a faster police response. With advances in telegraph—and later telephone—technology, calls to the police increased rapidly. A system of fifty signal boxes was installed in 1890 to allow city residents to alert the police if they needed assistance. The chief of police remarked that they “add greatly to the efficiency of the department.”[118] The public could and did signal—in 1893 the department received 206,539 calls—and policemen could also signal for backup or the patrol wagon.[119] The introduction of the telephone allowed callers to report more detailed information to the police, and was quickly adopted by Atlantans: telephonic reports increased from 146 in 1893 to 11,304 in 1901.[120] These new technologies meant that, rather than arresting only those whom the officers encountered in their patrols, policemen could rapidly respond to any report of disorder and make arrests.

These technological and organizational developments that made the force “modern” also increased the number of arrests that Atlanta’s officers could make, and the resulting pattern of racially disparate arrests and prosecutions is discussed in detail in Part III. First, however, it is necessary to examine the reasons why Atlanta’s police force exercised its power as it did. The answer to that question lies in how White elites understood the racialized causes of crime.

II. Lay Criminology: Connecting Blackness and Crime

Atlanta’s ordinances instructed police officers that “[t]he prevention of crime being the most important object in view, the patrolman’s exertions must be constantly used to accomplish that end.”[121] The category of “crime,” however, has always been socially constructed and cannot be disentangled from the broader quest for social control.[122] What is more, police resources are necessarily limited; the decision about how police should use their discretion in determining which criminals to pursue has always been a policy choice determined by beliefs about what causes and prevents crime. This Article labels these popular ideas about crime and its causes “lay criminology.” Although these ideas arose largely independently of the academic study of crime, they still had important influences on policing policy. This Part demonstrates that White Atlantans’ lay criminology, described and promoted by the city’s White-owned newspapers, helped to determine the policing policies described in Part III. This Part first analyzes how White writers linked crime to perceived Black unwillingness to work, and then explores how White lay criminology saw Black leisure activities as a source of serious crime.

A. Black Labor and Idleness

The White community’s consensus that crime was connected to Blackness and needed to be repressed by force was forged shortly after slavery.[123] More complex, however, were the perceived causes of Black crime, but the city’s newspapers quickly became leading proponents of a theory that posited that popular leisure activities caused Black crime.[124] The media’s focus on Black working-class leisure[125] influenced policymakers and made Atlanta’s dive bars and dancehalls common targets of police raids; the police justified petty arrests as preventing more serious crime.[126] The city’s leaders believed that modernizing the city and making it a regional leader required controlling crime and disorder and thus repressing Black leisure.[127] Black Atlantans, as we will see below, often dissented from the conclusions of lay criminology.[128] Their concerns, however, were usually ignored, except when they bolstered existing criminological narratives and provided support for police tactics.

Although anti-Black policing was justified using the rhetoric of crime prevention, the broader goal of social control was ever-present. White residents of Atlanta, informed by the city’s White newspapers, believed that many Black families moved to the city to lead lives of idleness and debauchery.[129] In addition, they believed the temptations of city life threatened to transform idleness into something even more dangerous and that the “criminal element” of the Black community could be found primarily in cities.[130] In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, White Southerners thus began to think of their Black neighbors not just as idle or vagrant, but as a “criminal class” whose very existence threatened the safety and security of city residents.[131] Because the press depicted idleness, vagrancy, and Black leisure activities as the causes of more serious crime, the White public supported police crackdowns on minor offenses and police control over the city’s Black community.

Even in the first years after emancipation, many White observers began to express the belief that Black Georgians were responsible for the city’s crime.[132] At this point, however, White Atlantans devoted little attention to the causes of crime—the effects of the Civil War and the end of the restraint of slavery seemed explanation enough.[133] In the 1870s and 1880s, however, White Atlantans began to formulate a lay criminology. Believing crime to be rising, as newspapers constantly reported, Atlanta’s leaders demanded that the police force root out behavior they considered criminogenic.[134] Race was at the heart of this lay criminology, but in creating the figure of the Black criminal, White Atlantans also considered how race intersected with unwillingness to work, alcohol consumption, and gender.[135] All of these various theories centered around the idea that Black Atlantans were predisposed to idleness and crime and that the coercion of slavery had been necessary to force them to labor.[136]

Many Black leaders, most prominently pastors, agreed with elements of this lay criminology. Most were strong temperance supporters and agreed that idleness, alcohol, and poor family life caused crime and should be repressed by the police.[137] They also argued, however, that social injustice, economic insecurity, and lack of access to education contributed to criminal activity—among both White and Black Southerners.[138] White powerbrokers, however, listened to Black leaders only when it was convenient—publishing anti-alcohol letters from pastors in the newspapers but ignoring their calls for justice and investment in the Black community and their protests against police brutality.[139] The key policy debates, then, centered on how to use the police to maintain social control and reduce Black idleness and its attendant criminality.

Even during slavery, White elites had complained of Black theft, but it was the movement of Black Southerners to cities, where “dangerous” entertainments like the dancehall supposedly replaced agricultural employment, that linked idleness and criminality in the White mind.[140] The fear that urban living contributed to idleness was enhanced by the Black unemployment that resulted from the various economic panics and recessions of the late nineteenth century.[141] The basic fact of Black employment patterns underlaid the White concerns about Black idleness. As noted above, nearly all Black workers engaged in low-paid manual labor. For many, employment was inconsistent, and they were frequently faced with days without work. There was no way for an observer to know if a man relaxing in a pool hall on a Tuesday afternoon was spending money he had earned the day before (or the morning of), whether he subsisted through theft, or some combination of the two. Unsurprisingly, White observers tended to assume the worst.[142] Former Navy Secretary Hilary Herbert, for example, presented the two issues as inextricably linked at a 1900 conference on Race Problems of the South: “idleness among the Negroes is undoubtedly growing, and crime appears to be increasing.”[143]

White writers argued that the source of increasing criminality was the generation of Black men and women born after emancipation, who reached adulthood during the 1880s. In their view, the new generation was idle, disrespectful, and criminal because it had lacked the guiding hand of a master to promote hard work.[144] For example, Walter Wilcox, one of the country’s foremost statisticians, believed that Black idleness and crime resulted from “defective family life and training,” that is, Black mothers, freed from slavery, were failing to raise their children properly.[145] White Southerners rarely linked crime to the social conditions in which Black Southerners lived or their inability to access education. Instead, they believed that idleness was rooted in biology and was the cause of both Black poverty and crime.[146]

Lurid coverage of crime, especially crimes committed by Black men, was particularly prominent in the tabloid press, but all of Atlanta’s papers printed stories about Black criminality from across the nation, contributing to the sense of a nationwide crime wave.[147] This view was supported by Northern social scientists who claimed that there was a strong “statistical basis for the well-nigh universal opinion that crime among the American Negroes is increasing with alarming rapidity.”[148] Northern support reinforced existing Southern notions of increasing Black criminality.

White writers often labeled idleness as “vagrancy,” a vague charge that could be used to make any leisure activity sound criminal.[149] In practice, any Black person not actively at labor in the workplace or home could be called a vagrant, regardless of their employment status. If arrested for a minor offense such as idling, the individual would be labeled a “vagrant” by the newspapers, and his or her misfortune presented as further evidence that crime was increasing.[150]

Once someone had been labeled a vagrant, they were excluded from even the limited set of rights that Black Southerners could be said to possess. The Atlanta Constitution,[151] the city’s leading White newspaper, frequently reported on Black idleness and vagrancy. In 1899, for example, it mused that Black lynching victims probably had not been steady workers. “[I]f they could not get wages for their work,” the paper declared, “they could at least have got their [room and] board. Anything would have been better than idleness.”[152] The narrative connecting idleness to crime is clearest in the paper’s long-running series of columns describing the goings-on at the Recorder’s Court.[153] Those columns often took on a comic tone, describing the trouble encountered by shiftless Black Atlantans for the entertainment of White readers.[154] Describing one Black man who appeared before the Recorder’s Court, the Atlanta Constitution wrote “[h]e is good natured, but every characteristic except laziness has long ago leaked out of his makeup,” which explained why he had been arrested multiple times for loitering and other minor infractions.[155] By mixing extremely minor offenses with more serious crimes, the column had the effect of reducing the distinctions between them, portraying the mass of Black Atlantans as consistently engaged in criminal activity.

Although White writers were concerned about Black idleness on its own, they also believed that idleness led to more serious crime.[156] Most obviously, newspapers consistently declared that those who did not work would survive by stealing and blamed any theft squarely on Black residents.[157] In 1875, for example, one newspaper blamed a string of robberies on Black residents, claiming that “[t]he negroes who rob and plunder are not the negroes who spend their days in labor. . . . It is the vagabonds who do the mischief.”[158] This idea persisted. In 1886, another newspaper praised the police crackdown on vagrants and asserted that “the criminal classes are recruited from the ranks of vagrancy. . . . From indirectly living a dishonest life to becoming a positive factor in the commission of a theft or some other crime, is but a step. Vagrants are criminals in the formative state.”[159] The conflation of idleness and criminality was an enduring theme of White lay criminology.

Although idleness was usually connected to theft offenses, some made the connection between idleness and more violent crimes, including rape.[160] In 1906 for example, a White woman named Autie Cox wrote to the editor of the Atlanta Georgian,

We never hear of a negro leaving his plow handles or hoe to commit this crime. It is invariably the idle, loafing, prowling negro who has no regular job, no permanent place of abode and who is satisfied if he has enough clothes to save him from public indecency and one square meal a day. This is the idle brain in which the desire is incarnate. Every city and town in the state has a lot of idle, loafing negroes who cannot be hired to do a good day’s work at any price and it is from this class that the rapist comes. Put them at work.[161]

Reflecting the White consensus about how to prevent Black crime, Cox proposed aggressive enforcement of vagrancy laws.

B. Black Leisure

Like working class people everywhere, many Black Atlantans escaped their drudgery by drinking, dancing, and playing cards, but Atlanta’s White leaders saw these activities as connected to crime and sought to repress them.[162] What is more, Black Atlantans had limited options for entertainment; for example, they were banned from newly built recreation sites such as the Ponce de Leon amusement park.[163] Consequently, Black Atlantans primarily patronized the commercial entertainments of Decatur Street, near the center of the city.[164] Although the street was described as a Black-controlled zone of iniquity by the White press, in reality it was a diverse area with a variety of forms of entertainment on offer, from food and shopping to dancing and vaudeville, and was one of the only areas in the city where Black and White residents could interact on anything approaching equal footing.[165] White Atlantans saw sites of relative racial equality and Black leisure as both a disorderly nuisance and a source of criminality and such spaces were thus targeted by the city’s police.[166]

The Black Atlantans who were labeled vagrants were not, of course, simply sitting on the curb. Outside of working hours, members of Atlanta’s working-class Black community filled their time with variety of activities, most of which, aside from attending church, were met with White disapproval. Many observers believed that these “hurtful amusements,” such as dives and pool rooms, tempted Black men and women away from work, encouraged idleness, and caused them to commit crimes.[167] Anyone present in such a location could be labeled a vagrant and arrested for disorderly conduct.[168] In this era of an increasingly powerful alcohol prohibition movement, many White Atlantans refused to distinguish between dark basement dives and more respectable “saloons,” and frequently blamed alcohol for a variety of crimes.[169] In 1901, the Atlanta Constitution voiced the widely shared opinion that alcohol consumption led to Black crime and resistance to police because Black people were “cowards when sober but bold and brutal when drunk.”[170]

Although any saloon that attracted Black patrons was considered potentially dangerous, Atlanta’s leaders considered the dance hall the most pernicious amusement because it combined idleness, alcohol, and the sexual overtones of dancing.[171] These dance halls were located largely along Decatur and Peters Streets, in the heart of Black Atlanta. Most of them were small, dark establishments, often located in basements, where men and women—primarily, but not exclusively, Black—could drink, smoke, play cards, and dance late into the evening to the sounds of a pianist or string band.[172] The potential for such intimate contact between the races, particularly when mixed with alcohol, was considered dangerous, especially to White women, and provided an additional basis for White opposition to Black leisure.[173] In 1901, Police Chief John Ball summarized the effect of dance halls and dives on crime, claiming there was “no more handy rendezvous for idling negroes than the poolrooms which are run on Decatur and Peters streets. All day long and far into the night these places are crowded with negroes who never work, and who drink, steal and gamble.”[174] Atlanta’s leaders believed that social control and crime prevention required a crackdown against such establishments.

Again, White Atlantans were not alone in their attacks on Black leisure. Black elites, especially religious leaders, were also hostile to many of the same activities. These leaders hoped to raise the first generation born in freedom with Christianity and respectability and were strong advocates of temperance.[175] Black patronage of dives and dancehalls, and the alcohol consumption that accompanied it, undermined this vision. Leading Black pastor Henry H. Proctor, for example, referred to dance halls as “dance hells” and asked the Atlanta City Council “in the name of God, in the name of Anglo-Saxon Civilization” to eliminate them.[176] Proctor also connected the establishments to crime, declaring that “[t]hese dens of vice and iniquity that cluster about saloons should be broken up: they are but hotbeds where thieves, cut-throats and rapists are hatched out.”[177] Even some younger and more radical Black writers shared this view. Atlanta Independent editor B. J. Davis repeatedly denounced dance halls, claiming that the “dancehall is the greatest social evil of the Negro race in the cities and larger towns of the South.”[178]

Black leaders also emphasized the detrimental effect that leisure activities had on Black women and home life and felt that dancing—because it was public, corporeal, and associated with drinking—was inextricably linked to sexuality.[179] Davis argued that the “fallen women” who patronized dance halls “should be given rescue homes to reclaim their souls for God instead of dance halls in which to steep and damp their souls.”[180] Later, his newspaper editorialized, “[t]he Negro will infinitely strengthen his hold upon employment if, instead of dancing and carousing the night away, he (and especially, she) will learn to become proficient in the task he is employed to perform.”[181] Another Black newspaper editor focused on the harm to young people, writing that dance halls “are doing more to ruin the young negro than any other agency I know of. To think that there are halls in this city where all day long young men and women who ought to be working are dancing and carousing makes some of us shudder for the future.”[182] Because women were thought to be responsible for imparting moral lessons to their children, opponents of Black leisure believed that the mother’s bad behavior would lead to criminality among the younger generation as well.

Both Black and White elites saw idleness, dancing, alcohol, and improper sexuality as intertwined. In Atlanta’s dives and dancehalls, they perceived an epidemic of immorality and criminality that called out for repression by police. Black leaders, like their White counterparts, called for police to attack the causes of crime by eliminating dives and forcing idle men to work.[183] In these calls, they demanded that the authorities repress criminality across racial lines, rather than focus exclusively on Black criminals.[184] As early as 1881, Black leaders asked the police to take action against Black leisure. Several of the “leading color[ed] citizens of the city” presented a petition which called for the abatement of dives which had “become the headquarters of the idle and vicious of the race.”[185] Such calls continued in the ensuing decades. Black leaders made similar forceful statements in support of rounding up Black vagrants and forcing them to labor on the chain gang. Proctor, for example, argued that vagrants should be arrested, writing that moral suasion “must be reinforced by the strong arm of the law.”[186] In 1903, the city council attempted to “abolish” dives and dance halls by setting a prohibitive $300 licensing fee. The fee did not successfully abolish dancing, but the press credited Black pastors, including Proctor, for accomplishing this change.[187] The city government, however, took no actions on Black leaders’ pleas for evenhanded justice.

Atlanta’s lay criminology was developed largely in the newspapers by White writers who believed that idleness and leisure encouraged Black criminality and could lead to more serious crimes, but it soon became more broadly accepted by both White Atlantans and Black leaders. These widely held ideas led the city’s police to target Black leisure establishments and make arrests for the minor offenses that Atlanta’s lay criminologists believed would lead to more serious crimes. No level of arrests, however, could puncture the media narrative that crime was increasing.[188] In fact, increasing arrests simply provided more content to fill the newspapers’ crime reports. Rather than calming White fears, reports of the ever-rising arrest rate and the sight of Black men and women working on the chain gang in stripes furnished further proof that Black Atlantans were increasingly criminal and in need of police control.[189] This vicious cycle fueled both White fears and the growing criminalization of these minor offenses. The increase in criminalization had a major detrimental impact on Atlanta’s Black community, as demonstrated in the next Part.

III. Criminalization in Practice

To translate the lay criminology of Atlanta’s elite into practice, the police made mass arrests for minor offenses associated with idleness, especially at Black leisure establishments. This mass arrest policy both helped to ensure White supremacist social control and, in theory, reduced serious crime. This policy also caused Atlanta to have the highest arrest rate in the country at the turn of the twentieth century.[190] A significant majority of those arrested each year were Black, even though Black Atlantans represented only between 40 and 46 percent of the city’s population.[191] In 1901, for example, 65 percent of those arrested by the Atlanta Police were Black.[192] This Part argues that the disproportionate arrest and brutalization of Black Atlantans were a result of the police’s broader goals of maintaining order and punishing the leisure activities of Black residents.[193] After arrest, Black Atlantans were tried in the Recorder’s Court where the lack of due process caused thousands to be convicted and assessed onerous fines.[194] Those who could not pay were forced to spend weeks building the city’s streets on the chain gang. Whether they paid cash or paid with their labor, the criminalization of Black Atlantans materially benefitted the city. This Part first describes Atlanta’s arrest pattern and analyzes why a majority of arrestees were Black residents charged with minor offenses. It then explores the trial of criminal defendants in the Recorder’s Court and the punishments faced by those convicted.

A. Arrests and Policing

As soon as a modern police force was created, Atlanta’s arrest rate increased significantly and soon began to outpace comparable cities. In 1874, even with arrest fees for policemen eliminated, Atlanta’s police arrested 3,605 people, 60 percent more people than the old force had in 1873. Of those arrested, 2,078 were Black.[195] Although Savannah’s population was nearly identical to Atlanta’s, its police force, which dated from the antebellum period, made far fewer arrests. In 1874 Savannah’s force arrested only 2,021 people, 55 percent of them Black.[196] The number of arrests in Atlanta grew rapidly from there. Ten years later, in 1884, the city’s police arrested 3,247 Black Atlantans out of a total of 5,824 arrests.[197] In 1904, those numbers had grown to 11,954 and 18,556, respectively.[198] Between 1880 and 1890, the number of arrests far outpaced population growth, with the arrest rate increasing from 116 per thousand to 195 per thousand.[199] Black Atlantans were arrested in significantly greater numbers than White Atlantans, and their arrest rate increased more rapidly: between 1884 and 1900, the arrest rate for Black Atlantans nearly doubled from approximately 148 per thousand to 285 per thousand.[200] When we compare arrest rates among women, the disparities are even starker. In 1896, for example, eight times as many Black women were arrested as White women.[201] In addition, many Black children were arrested. In 1896, 696 Black boys and forty-eight Black girls under the age of fifteen were arrested. They received no special treatment because of their age and were tried as adults.[202]

The arrest rate for Black Atlantans peaked in 1901. That year, 11,502 Black men, women, boys, and girls were arrested, representing 64.5 percent of the 17,826 total arrests.[203] The arrest rate for Black Atlantans that year was 322 arrests per thousand, more than three times the rate of 106 per thousand for White Atlantans.[204] Presumably some defendants were unlucky enough to be arrested multiple times each year, but even so, the city’s arrest rate was still extremely high: each year, the Atlanta police arrested a number of Black people equivalent to almost one-third of the city’s Black population.[205]

Black men consistently accounted for the highest number of arrests for any group throughout the period.[206] After 1890, however, the arrest rates for Black and White men diverged, and the arrest rate for Black men spiked. In contrast, the number of Black women arrested grew relatively constantly across the period.[207] Many factors, including the growing number of police officers, contributed to the sudden increase in Black male arrests, but this Article concludes that the most important factor was the increasing police focus on conducting mass arrests at dives, the imperative of the lay criminology consensus.

Figure 1. Arrests by Race and Gender

The vast majority of those arrested, whether Black or White, were accused of minor crimes. The proportion of arrests for crimes under state law—as opposed to city ordinances—was quite low. State crimes included major offenses such as murder, burglary, and rape, but also included less serious property crimes such as larceny. State crimes accounted for 22 percent of all arrests in 1876, but that proportion dropped steadily over time, bottoming out at 7.5 percent in 1901.[208] Between 1890 and 1906, there were only two years in which the proportion of state crime arrests reached 15 percent.[209] What is more, many of these state crime arrests did not lead to state crime convictions.

In 1903, for example, more than 60 percent of state crime cases were dismissed or transferred to the Recorder’s Court to be tried as city offenses.[210] This left only 290 state crime defendants prosecuted in Fulton County, where Atlanta is located, with 213 more extradited to be prosecuted by nearby counties.[211] Of 16,088 arrests in 1903, then, at most 503 resulted in felony cases.[212] Despite media coverage that highlighted violent crimes, the police focused their attention on petty offenses. As late as 1903, the police employed only eight detectives, making it difficult to investigate serious crimes.[213] Consequently, in addition to arresting Black Atlantans for minor offenses, the police did little to investigate serious crimes committed against them, whether by White or Black perpetrators.[214]

Throughout this period, minor crimes thus accounted for more than three quarters of arrests in Atlanta.[215] This reality led one chronicler of the city to claim that Atlanta was “a law-abiding city, barring, of course, the many petty offenses resultant from a large negro population.”[216] The most common charges for both men and women were petty violations such as drunkenness, disorderly conduct, and other order-maintenance offenses.[217] Between 1893 and 1906, arrests for drunkenness alone exceeded all state crime arrests.[218] In every year in that period, drunkenness and disorderly conduct together comprised the majority of arrests.[219] When the crime of “idling” (i.e., loitering) is included, the proportion of public order arrests is even higher, peaking in 1904 when 83.5 percent of arrests were either for drunkenness, disorderly conduct, or idling. The vagueness of these offenses allowed police officers to enforce the law at their discretion with little risk that the arrestee would be acquitted or that the officer would be successfully sued for false arrest.[220] The proportion of arrests for minor violations was extraordinarily high, even when compared to the twentieth century.[221]

Importantly, Black Atlantans were not being arrested in large numbers under new laws that were passed after emancipation to control freedpeople.[222] Although elites referred to many of those arrested as “vagrants,” they were rarely prosecuted under Georgia’s vagrancy law.[223] In 1894, for example, the police chief’s annual report listed only two arrests for vagrancy, and in 1905 it listed just one.[224] Vagrancy was a disfavored charge because a defendant could be acquitted if he or she presented evidence, such as testimony from a supervisor, that he or she was employed.[225] Nevertheless, the press’s constant references to Black arrestees as “worthless vagrants” who were also implicated in more serious crimes helped build support among the city’s White population for crackdowns on minor offenses.[226]

Instead, the Atlanta police arrested Black residents for the same minor offenses that were used to criminalize working-class people everywhere.[227] From the perspective of the police, the virtue of disorderly conduct and similar violations was that they were discretionary “catch-all” offenses and could be employed to achieve the goal of maintaining order and cleaning up the streets.[228] Police took advantage of the fact that, in this period before Papachristou, there were effectively no Constitutional restrictions on the vagueness of local ordinances.[229] Indeed the Atlanta police arrested hundreds of people every year “on suspicion.”[230] Observers recognized that the guilt or innocence of a person arrested for these vague offenses lay in the hands of the policeman who chose to make the arrest.[231] In short, mass arrests for petty offenses left defendants with little recourse against police officers’ discretion.

Because the vast majority of arrests were for public order offenses, Atlanta’s arrest rate was determined by police tactics rather than by the actions of the city’s residents. Influenced by the lay criminology promoted by Atlanta’s media,[232] the police force began to be more proactive. Starting in the mid-1880s, the police force increasingly began to go out to find—or rather, create—criminals, arresting Atlantans for disorderly conduct or drunkenness before they could, theoretically, commit worse offenses.[233] As one newspaper summarized this preventative theory: “It is easier to crush the egg than to catch the eagle it will hatch out.”[234]

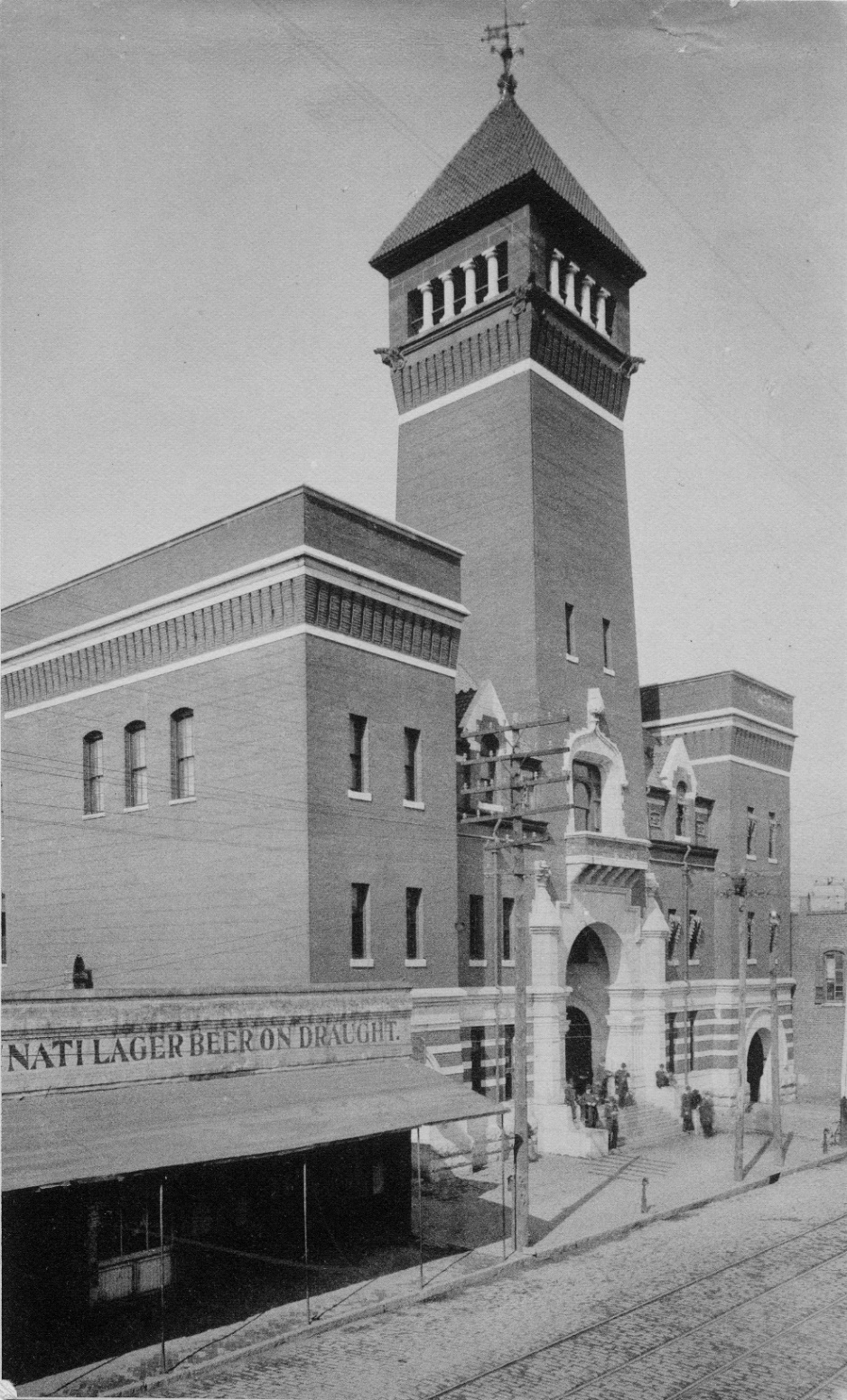

Figure 2. Atlanta Police Headquarters, 1890.[235]

Figure 2. Atlanta Police Headquarters, 1890.[235]

To achieve their goal of increasing arrests for minor offenses, the police targeted sites of Black leisure with frequent raids. This strategy was aided by relocating police headquarters to an imposing new building on Decatur Street in 1890, in the heart of Black Atlanta’s leisure district.[236] This juxtaposition was purposeful: The new police headquarters was an imposing symbol of White supremacy, looming over space which Black Atlantans considered their own. The station’s location was a physical representation of the police force’s priorities. The station’s location assisted with the department’s strategy of raiding dives to sweep up low-level offenders in what the city’s leaders considered “breeding places of crime.”[237] From the earliest years after the department’s creation, the police were “determined to break up riotous negro dances,”[238] but such raids expanded drastically in the late 1880s when the police began to institute frequent crackdowns on “vagrants.”[239] These raids could result in dozens of arrests in a single evening and significantly increased the racial disparity in arrests between Black and White men. To take one example, just after midnight on a Sunday in June 1897, the police raided Good Samaritans’ Hall and arrested fifty people. The arrestees, whose Saturday night revelry had carried over into Sunday morning, were charged with disorderly conduct for “dancing, playing cards and drinking beer on the Sabbath day.”[240] The Atlanta Constitution noted that because each arrestee was fined $3.75 “the raid netted the city about $150.”[241] This strategy of periodic raids continued for decades. When John Ball became police chief in 1901, he declared a “war on vagrants” and launched a raid that netted 114 people in a single night.[242] In his words, the raid “was the outcome of the recent determination of the mayor and the police authorities to rid the city of the loafers and vagrants by putting as many of them as possible in the chaingang [sic].”[243] By 1903, the clerk of the Recorder’s Court estimated that nearly half of cases at the Recorder’s Court were connected to raids on dives and dance halls.[244]

Atlanta’s version of order-maintenance policing was distinct from the anti-vice policing that later grew across the nation, especially after 1910, in which police focused on repressing offenses against public morality such as gambling and prostitution. In both instances, political leaders were concerned with protecting White women’s virtue from supposed crime and danger, especially at the hands of Black men. In Atlanta, however, the police did not focus on policing prostitution and there was not an attempt to “contain” vice in a “red-light district” during this period, though such efforts became common in the early twentieth century.[245] Rather, Atlanta’s police focused on sites of alcohol consumption primarily because the city’s leaders saw alcohol consumption as a major cause of crime for both men and women. Although alcohol was allowed to be sold throughout the period, except between 1885 and 1887 when Fulton County went dry, there were numerous restrictions and license fees and some, but far from all, of the dives raided by the police were unlicensed “blind tigers.”[246] Regardless of the legality of alcohol, the discretionary nature of offenses, such as disorderly conduct, allowed the police to arrest all the patrons of any establishment they chose to raid.

The most important result of Atlanta’s police tactics was the sheer volume of arrests. What accounts for Atlanta having a much higher arrest rate than other similar cities, such as Savannah, and indeed having the highest arrest rate in the country? One factor was that Atlanta employed more police per capita. In 1890, Atlanta employed one officer per 537 residents while Savannah employed one officer per 675 residents. In 1900, those rates had grown more disparate, with one officer per 473 and 624 residents respectively.[247] The size of Atlanta’s police department, however, was downstream of the broader goals of rapid growth discussed above. Those same goals led Atlanta’s police to embrace proactive, order-maintenance policing. Rather than invest resources into solving or preventing major felonies, the department focused on arresting Black Atlantans for low-level status offenses, such as disorderly conduct and drunkenness. Overall, the police’s discretion allowed them to make any arrest necessary to uphold the city’s racial hierarchy.[248] Atlanta’s leaders believed that making arrests for petty offenses would both help control the city’s Black population and help reduce more serious crime.

B. The Recorder’s Court and Punishment

Arrest by a police officer was only the first step into the criminal legal system. After being arrested, Atlantans would be booked into the jail beneath the police station, which one newspaper described as a dungeon that “looks about as repulsive as a place of the kind could well look.”[249] “Many a hardened criminal immured there,” it continued, “would gladly have pleaded guilty to any crime.”[250] The next day—or on Monday if the arrestee was unfortunate enough to be arrested on a Saturday—the accused would appear before the Recorder’s Court where the fate of thousands of Atlantans each year was decided. Those facing trial for state crimes would be arraigned and then held to await trial in the Superior Court.[251]

The Recorder’s Court was established in 1872, replacing the Mayor’s Court where the mayor himself decided the fate of those accused of minor offenses.[252] The recorder was chosen by the mayor and city council and required to post a $5,000 bond to hold office.[253] The Recorder’s Court had jurisdiction over all offenders against city ordinances and had the power to bind over to the Superior Court those who violated state laws.[254] Although the Recorder’s Court had jurisdiction over a wide variety of ordinances, including the building, health, and fire codes, most cases were for petty violations, such as disorderly conduct. The recorder could impose the maximum punishment allowed by ordinance or, if no punishment were specified, could exercise his discretion to punish offenders with fines up to $100, a term of imprisonment of up to six months, or up to one year on the city’s chain gang.[255] The recorder thus had essentially unreviewable authority to dismiss charges or to determine that the defendant labor on the chain gang.[256]

The proceedings of the Recorder’s Court were frequently covered in the city’s press.[257] These articles were often comical and contributed to Atlanta’s lay criminology by portraying Black defendants as ignorant and innately criminal.[258] Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., the son of the Atlanta Independent editor, wrote that the court “provided a form of entertainment, of sport, for the petty officials, at the expense of the hapless, humble Negro workers caught in the complicated toils of jim-crow laws.”[259] The recorder frequently made racist remarks for which he received supportive coverage in the city’s White papers. The Atlanta Constitution reported that the long-tenured Recorder Andy Calhoun, for example, “can tell the guilt or innocence of a negro by the expression he wears, and is perfectly familiar with ever species of the genus Africanus.”[260] It is not surprising, then, that the recorder used his discretion to disproportionately punish Black defendants.

The primary characteristic of the Recorder’s Court was the high volume of cases that it handled. As the city council declared, the court was created “with a view to the suppression of crime and the bringing of offenders to speedy justice.”[261] As early as 1872, it was reported that twenty-two cases per day came before the court, but the caseload increased quickly.[262] On one day in 1909, the court adjudicated a record 160 cases.[263]

Contemporary notions of due process had no place in the Recorder’s Court. Trials lasted, at most, a few minutes. Defendants were allowed to be represented by counsel and to call witnesses in their own defense, but finding representation and even witnesses was difficult because most defendants were tried the morning after they were arrested.[264] As a result, nearly all defendants appeared without an attorney. In addition, a Recorder’s Court docket book that covers the period between June 1886 and April 1887 reveals that 65 percent of the 3,699 defendants who appeared before the recorder had no witnesses testify in their defense.[265] Consequently, most cases came down to the testimony of a police officer against the testimony of the accused.[266] Attorney Alexander Akerman accurately described the process of being tried by a recorder: “[T]he result is inevitable. The prisoner is promptly found guilty of one or more of the charges, fined beyond his ability to pay, and in default thereof hustled to the chain-gang [sic].”[267] In addition, a clear racial disparity emerges in dismissal rates: 57 percent of White men had charges dismissed compared to 45 percent of Black men and only 32 percent of Black women.[268]

The Recorder Court’s fines were particularly onerous for Black Atlantans, the vast majority of whom made less than one dollar per day—with Black women making even less than that amount.[269] The docket book reveals that even relatively small fines often forced Black Atlantans onto the chain gang. For Black men, the average fine for disorderly conduct that resulted in time on the chain gang was $7.78.[270] For Black women, it was even lower: $6.70.[271] In contrast, White men who ended up on the chain gang were assessed, on average, a significantly higher fine of $11.31, reflecting the fact that White Atlantans generally made higher wages and thus had more resources to pay fines.[272] Consequently, in the period covered by the 1886–87 docket book, 382 White men and 32 White women were sent to the chain gang.[273] In contrast, 462 Black men and 191 Black women ended up laboring on the city’s streets.[274]

That year, then, Black Atlantans comprised approximately 61 percent of those sent to the chain gang, though they made up approximately 44 percent of the city’s population. As noted above, the arrest rate, and consequently the proportion of men and women sent to the chain gang, became even more racially disproportionate in the 1890s. Although there was some variation around the state, it appears that fines were generally worked off at a rate of fifty cents per day in Atlanta—thus if a man were unable to pay a five-dollar fine, he would be forced to labor without pay on the chain gang for ten days.[275] At that rate, Atlantans provided almost 70,000 man-days of unpaid labor working the city’s streets in 1896.[276] Moreover, the raw number of individuals who served time on the chain gang understates the total proportion of annual chain gang labor done by Black Atlantans. In 1904, the Atlanta Constitution reported that Atlantans served 79,510 days on the chain gang, with Black prisoners accounting for 85 percent of the total.[277]

Though convicts were rarely forced to work on the city’s chain gang for more than a month, the conditions were dismal.[278] Prisoners were frequently whipped as punishment for small offenses and the “stockade” where they were housed was infested with cockroaches and rats.[279] Although there were few formal collateral consequences of conviction, there were still numerous downstream effects.[280] Spending weeks on the chain gang meant being separated from one’s family and unable to support them. This was particularly harmful for Black Atlantans because many Black families required the earnings of both parents to purchase the necessities of life and had few savings to draw upon when the wages of one parent were lost.[281]

Figure 3. Atlanta Chain Gang circa 1905.[282]

This system of fines and chain gang labor materially benefitted the city. In 1903, for example, the value of fines paid amounted to almost one quarter of the police department’s budget.[283] Chain gang labor had even more tangible benefits. As early as 1875, the Police Committee argued that when “the benefit derived to the City from the labor of the Police Court convicts are considered, it will be readily seen that the actual expense [of the police force] is greatly reduced.”[284] The next year, the Streets Committee of the Council reported that while it was regrettable that so many Atlantans violated the law, “we believe that these convicts furnish the cheapest and most efficient laborers we can get for our streets and we recommend that measures be taken to secure by legislation their continued service.”[285] Chain gang prisoners worked to construct new and better roads that supported Atlanta’s rapid expansion. The city thus had little financial incentive to avoid unnecessary arrests, particularly because its growth and prosperity attracted new migrants—many of whom would themselves end up on the chain gang. The Recorder’s Court punishment practices are part of a long American tradition of using criminal law to generate revenue and subsidize the expansion of carceral institutions.

In contrast to Malcolm Feeley’s famous description of New Haven’s municipal courts, in Atlanta’s Recorder’s Court, the process was not the punishment.[286] Rather, after minimal process, defendants were subjected to heavy fines or forced labor on the chain gang. In 1906, reformist attorney Alexander Akerman summarized the state of local justice in a speech to the Georgia Bar Association. He labeled municipal courts the “greatest menace of the present time to the liberties of the people” and declared that such courts “daily and hourly consign the indiscreet, the helpless and the poor to an involuntary and public servitude in chains, under the public lashings of the whipping boss, not for crimes but for petty municipal offenses, for which no such punishment is meted out by the authorities of any other civilized people.”[287] Akerman’s indictment was rare among White Georgians, but was common among Black Atlantans of all classes, as demonstrated in the next Part.

IV. Black Challenges to the Crime and Policing Consensus

With a few minor exceptions, discussed above, Black Atlantans had little direct impact on elite criminological theories or on policing policy.[288] From the first years after the Civil War, however, they engaged in various forms of protest against policing and the criminal legal system. This Part describes the differences between the activism of the Black middle and working class, but nevertheless demonstrates that Black Atlantans were unified across class lines in their opposition to racist explanations for crime and biased policing.

As early as 1867, Black Savannah politician James Simms expressed a widely held sentiment, declaring, “we want no bigoted Mayor and no brutal policemen” but rather Black political power.[289] That same year, Black Atlantans demanded, unsuccessfully, that the city hire Black policemen.[290] This Part shows that such formal demands were characteristic of Black elite and middle-class activism, while working-class Black men and women had more direct ways of making their voices heard. Such bifurcated Black protest activity would continue across the ensuing decades. This Part demonstrates that contemporary calls for reform and protests against racist policing are part of a tradition that dates to emancipation itself. This Part first examines the written protests and alternative criminology put forward by middle-class and elite Black Atlantans. It then demonstrates that working-class Black Atlantans more directly challenged the authority of the Atlanta police.

A. Elite and Middle-Class Activism

Atlanta’s Black leaders challenged both the White criminological consensus and racist criminal justice practices. In doing so, they put forward an alternate vision of crime prevention that focused on material inequality. Atlanta’s Black leaders and middle-class professionals denied White claims that there was an inherent connection between Blackness and criminality. As W. E. B. Du Bois, a professor at Atlanta University between 1897 and 1910, declared in his 1904 study Notes on Negro Crime, “the Negro is not naturally criminal.”[291] As shown above, Black leaders still frequently criticized the elements of the Black community they believed were responsible for crime,[292] but they argued that crime was essentially a problem of class, not of race.[293] In the words of pastor Henry H. Proctor, Black leaders sought to distinguish “the educated, property-holding or church going element of the colored race” from the “worthless, irresponsible vagabond.”[294]