Introduction

Since the 1970s, Indian policy has been guided by a federal commitment to tribal self-governance. The exact contours of this policy differ, but at a minimum, it is supposed to guide the approach of the federal government in its relations to tribes. Where state and private interests collide with tribal interests, the role of the federal government is often as a mediator of competing claims. In a sensitive and insightful piece, Professor Charles Wilkinson illustrates the way collaboration is supposed to work. He describes the process through which the tribes and the federal government negotiated the creation of what he calls “the first native national monument.”[2] That description reflects what Professor Wilkinson believes is a turning point in the relationship among tribes, states, federal agencies, and private stakeholders in untangling the historically constituted web of interests that bedevil a fair adjustment of interests in land and resource management. U.S. colonial expansion into Indian Country meant that non-native expectations had priority in disputes over policy and law. The western movement was accompanied by presumptions about rightful claims to land and resources that are attendant to the American expression of settler colonialism. Professor Wilkinson illustrates that the physical landscape and the legal relations in which that landscape is embedded require careful attention to the mutual dependence of sacred relations and the more secularly denominated ecosystemic services.[3] Co-management agreements can create a legal space where the various competing interests can be accommodated in a way that reduces the cost of conflict.

The congeries of legal sources available for directing any specific action complicates using law as a guide for reframing relations between the tribes and their prior antagonists. The sources of law range from treaties to foundational statutes like the Northwest Ordinance or the Non-Intercourse Act.[4] As illustrated by Professor Wilkinson, the Antiquities Act[5] provided the legal foundation for the creation of Bears Ears National Monument, but it was the cooperation of the tribes, who shared a long and deep connection to the area, that proved essential for providing the substance necessary for the shaping of the monument. These tribes included the Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Uintah and Ouray Mountain Ute, and the Navajo nations, who together created the Inter-Tribal Coalition, which provided early leadership during the creation of the monument.[6] The shaping was as much conceptual as physical. By combining the traditional knowledge of the tribes with federal land management practices, the creation of the monument demonstrated how federal land and resource management in the West ought to proceed.[7]

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines co-management as “a process of management in which government shares power with resource users, with each given specific rights and responsibilities in relation to information and decision-making.”[8] One of the hallmarks of co-management is the recognition that different knowledge systems can improve decision-making. While co-management is an imprecise term lacking a single, agreed-upon definition, the term usually refers to a spectrum of institutional arrangements through which users and other stakeholders share the obligations and responsibilities of management.[9] In the context of tribal co-management agreements that are defined by treaty obligations, one must also consider how both sovereignty and the federal trust duty are understood.[10] This point needs to be underlined because co-management agreements between tribes and states always include at least three sovereigns: the tribes, the states, and the federal government. Typically, the federal government acts as a trustee for the tribes, but the tribes themselves get to determine their interests. As I discuss below, treaties create special obligations for the federal government and represent pre-commitments that are absent in regulating ceded land over which the tribes have aboriginal, but not treaty or statutory, interests.

Treaties will structure the broad outlines of responsibility, but the courts have played, and likely will continue to play, an important background role. The long trail of decolonization—and with it the gradual recognition that tribes should govern themselves and be free to make decisions that are central to their sovereign status—should inform our understanding of the politics of resource management. While states have long maintained a preemptory position, the Supreme Court has been clear that unless Congress acts, rights and resources secured by treaties survive the entry of states into the union.[11] A state and a tribe even negotiate an agreement concerning resource management in the shadow of treaty rights and treaty conflicts. While parties cannot ignore the political and property regimes that guide expectations, courts provide techniques to understand the treaties’ specific words. The conflicts that plague resource management on public lands, especially where the management of those public resources implicate private land (whether native or non-native), have their roots in disputes over treaties.

Treaties between tribes and the federal government are contentious. Their exact legal status and the rights attendant to them have long been fraught. One such example is Congress removing the constitutional foundation in an 1871 rider to the Indian Appropriations Act. It stated that:

No Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty; but no obligation of any treaty lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe prior to March 3, 1871, shall be hereby invalidated or impaired.[12]

Removing treaty power from the executive emboldened states to use other arguments to limit tribal rights. In one example, states used the equal footing doctrine to impliedly repeal treaty guarantees.[13] Despite constant attempts to limit tribal rights, courts have mostly sustained tribal sovereignty by considering tribes domestic and dependent nations under both treaties and executive orders.[14] Although clothed in sovereign and jurisdictional claims, the conflicts have almost always been local, as the pressure on the ground over resource use translates into legal action. Conflict arises between the precise contours of tribal power and to what extent states may limit those powers.

As recently as 2018, an equally divided Supreme Court affirmed states’ duties to honor treaty obligations and manage resources in a method consistent with those obligations.[15] In Washington v. United States, the Washington tribes claimed that the state may not act in ways that materially diminish the fishery resource, especially salmon, even if the actions by the state were not intended to reduce the resource but were nonetheless a predicable consequence. The state resisted, asserting that it would result in the tribes having an environmental right that was not contemplated by the treaty. Determining the extent of the tribes’ rights required careful attention to the demands of the treaty. By studying the litigation arising from the Stevens Treaties, this Essay explores what obligations the state might have to the tribes (and vice versa) and whether co-management agreements can prevent the dead weight associated with litigation, an allocative inefficiency caused by the market distortions that legal disputes often produce.[16] By looking at co-management agreements, while recognizing that they cover a variety of resources, this Essay aspires to catalog and evaluate the agreements from an efficiency perspective as well as from a perspective of mutual obligations for the provision of environmental services.

The legal struggle between Stevens Treaty tribes and the State of Washington has persisted for over a century. Washington resisted the requirements derived from the Stevens Treaties almost from the beginning.[17] Multiple treaties comprise the Stevens Treaties, and they involve most of the tribes in what is now Washington and parts of Idaho and Oregon. While they go by a variety of names (such as the Treaty of Hellgate, the Point Elliot Treaty, and the Quinault Treaty, among others), they are commonly grouped together because of the role Governor Stevens played in their formation. As Kent Richards summarized:

In 1854, Stevens met in Washington, D.C., with Manypenny and his second-in-command, Charles Mix, concurrent with the commissioner’s treaty sessions with the Kansas-Nebraska tribes. Before Stevens returned to Olympia, Mix, acting for Manypenny, issued written instructions to the governor. His directive reiterated that Stevens had been appointed to conclude “Articles of Agreement & Convention with the Indian Tribes in Washington Territory,” a region stretching from the divide of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.[18]

The treaties at issue in the litigation affirm, among other things, the right of tribes to take salmon in common with non-Indians at all of the customary places.[19] The question facing the Court in the most recent litigation was whether there were additional obligations on the states to ensure the continued sustainability of the resource.[20] This question, especially in times of climate disruption, is critically important to tribes and their members. The impacts of climate change, for example, have had dramatic impacts on the variability of water that affect the salmon fisheries as well as the irrigation claims of farmers and other claimants to the water.[21] In addition, those tribes that depend on shellfish fisheries are seeing a direct impact on the health of those fisheries.[22]

Consistently enforcing obligations claimed by the tribes would also benefit non-Indians and would highlight the fundamental structure of trust duties that a state owes to its people. Litigation over resources demonstrates that the states are bound by treaty commitments and that those commitments require states to balance competing demands reflecting that all stakeholders’ rights are equal. The treaty litigation shows that all decisions, even those that are only indirectly tied to a specific resource decision, are clothed in the general trust duty to safeguard public resources. Litigation also increases the costs of decision-making without necessarily improving the long-term outcome.

Treaties and Competing Sovereign Claims

As the famous Marshall Trilogy shows, a central issue facing European settlers was how to navigate relationships with the people they encountered.[23] This Part argues that treaty-making created political and practical conflicts rather than completely resolving the status of the tribes. It then describes the nature of the jurisdictional disagreements and shows how tribal claims to resources amplified those disagreements, especially when the tribes maintained claims to resources outside the boundaries of their reservations.

Almost immediately, settlers began to navigate these relationships with the use of treaties. As political bodies, tribes could make treaties with the British Crown. After the colonies declared independence, the unsettled relationship between the tribes and newly sovereign states was a constant source of tension. The main practical concern of the new government was reducing hostilities on the frontier. Prior to the adoption of the Constitution, debates revolved around jurisdiction over tribes within the territory of the states. The Marshall Trilogy clarified that states had no jurisdiction over activities occurring on tribal land.

The states initially claimed jurisdiction over Indian affairs in the Articles of Confederation.[24] After the adoption of the Constitution, the states continued to resist the primacy of federal jurisdiction. The litigation between the Cherokee and the State of Georgia (the principal antagonists in the Marshall Trilogy) was concerned precisely with the reach of state jurisdiction. The state claimed both the right and power to regulate within its borders, including those lands which were retained by treaty for the tribes.

From the beginning, conflicts arose due to differences in how parties interpreted treaties. The legal nature of treaty obligations was at the center of those controversies.[25] Since the federal war of extermination ended, the states have been tribal sovereignty’s most dogged enemy due to competition over local resources and control of local populations.[26] The conflict between settlers and natives, aside from the brutality of war, was further complicated because converting federal territory to states throughout the West involved previous promises made to tribes.[27] The tribes had ceded much of their ancestral territory to the United States in exchange for land and other rights guaranteed by treaty, statute, and executive order. Under the “equal footing doctrine” (the rule that permits only one class of states within the Union), states challenged the status of both tribal land and treaty rights for access to land outside of tribal territories. The newly admitted states claimed that permitting tribes to have territory and exercise jurisdiction would violate the equal footing doctrine.

Fishing rights litigation among states, tribes, and the federal government exemplifies the conflicts surrounding both resource use and tribal and individual rights to access resources outside of Indian Country.[28] For example, in the early litigation pitting the Yakama tribe against Washington State, the state claimed that the litigation did not involve sovereignty at all.[29] According to the State Attorney General, Slade Gorton, the disputes were ordinary, private disputes between individual Indians and private non-Indian landowners. Based on Gorton’s theory, any disputes could be resolved through the state law of trespass. Washington denied that the treaties could have contemplated a relationship between tribes and the states because the states did not exist at the time of the treaties were signed.[30] Washington argued that the state was not beholden to tribes based on the fact that many states were carved out of federal land the tribes had previously ceded. Despite the reality that tribes preexisted states, the states continued to assert a superior right to the land and its resources.

The states continued to claim this superior right despite the accommodations made to prevent non-Indian encroachment through treaties with the federal government. Using the equal footing doctrine to justify suspending or terminating treaty rights was supported in part by Ward v. Racehorse,[31] but that argument was dismissed by the Supreme Court in Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians[32] and finally fully overruled in the 2019 term in Herrera.[33] Admission of a territory to statehood does not terminate treaty rights or obligations. If Congress wants to change the relations between tribes and states that are protected by treaty (or by statute), it must do so explicitly.[34]

Treaties, like the Stevens Treaties, predate the creation of the states.[35] The preexisting obligation did not quiet the piteous mewling of the states who thought the large amount of land the tribes ceded was insufficient. Treaties were independent obligations entered into by the United States in exchange, typically, for peace and for land. While tribal treaties have always been a source of juridical controversy,[36] they represent a political settlement between sovereigns and form a backdrop against which states’ claims should be assessed. In addition to being part of the supreme law of the land,[37] treaty rights may not be limited absent an unambiguous expression from Congress.[38] The treaties, rights, and powers guaranteed to tribes should be understood as the background against which state police power is measured. These rights and powers are founded in federal law and grounded in retained tribal sovereignty; they were not meant to be temporary accommodations recognized only until the land was parceled out into states.

Conflicts over resource use were common. In fact, these conflicts were the engine of the westward expansion that displaced native people from their lands.[39] As the vast territories were reduced to reservations, many treaties protected the rights of tribes to hunt and fish in their normal and accustomed places, including ceded non-reservation land. These protections took the form of treaty-warranted easements across public and private land. Non-Indians resisted tribal members’ efforts to exercise these rights, sometimes violently, sometimes by trying to expand state jurisdiction to do the work for them.

Under the Stevens Treaties,[40] tribes in the Pacific Northwest ceded approximately sixty-four million acres of land to the United States, reserving small reservations for their own use and securing fishing rights on off-reservation land.[41] Each of the treaties that make up the Stevens Treaties preserves fishing rights through a “fishing clause” that assures tribes “the right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations . . . in common with all citizens of the Territory.”[42] “[U]sual and accustomed grounds and stations” include off-reservation customary fishing sites,[43] many of which were compromised by both federal hydroelectric projects and the expansion of commercial fishing by non-Indians.

Current litigation concerning these fishing rights considers whether those rights permit tribes to contest actions that would deplete fisheries by making it impossible for fish to return to their spawning grounds. In the context of environmental regulation, the central question is whether treaty parties must provide the environmental services necessary to underwrite treaty guarantees. Put plainly, does the right to fish necessarily include the power to protect the continued availability of fish?

This Essay next explores litigation arising from the Stevens Treaties and considers the nature of treaty obligations and whether co-management agreements are more efficient than litigation. This formulation, of course, presumes that there is an optimal level of fish and infrastructure that could be achieved.[44] I evaluate a number of co-management agreements. These agreements raise efficiency claims as well as claims of potential obligations for the provision of environmental services that flow from treaty obligations.

The Washington Litigation

Due to the complex nature of treaties and their attendant rights, even the judiciary has struggled for over a hundred years to define the precise scope of the fishing clause in the Stevens Treaties.[45] In United States v. Winans, the United States sued the Winans brothers, non-tribal commercial fishermen who owned land including a Yakima customary fishing site.[46] Not only did the Winans brothers prohibit the Yakimas from accessing the site, they also installed fishing wheels, devices capable of catching salmon by the ton. They claimed the exclusive right to operate the wheels under a state fishing license.[47]

The Winans brothers argued that, by granting fishing rights “in common with the citizens of the Territory,” the Treaties only guaranteed the Yakimas and other tribes the same fishing rights the general public possessed.[48] Therefore, according to the brothers, the Yakimas could fish on public lands, but not privately owned lands. The Supreme Court rejected this argument and held that the fishing clause granted the Yakimas’ fishing easements for customary fishing sites, including those on private land.[49]

The Court noted that treaties with tribes should be construed as the tribes would have understood them at the time they were signed and “as justice and reason demand.” The Court reasoned that the tribes would not have agreed to such an “impotent outcome” as securing only those fishing rights they would have held as members of the general public even if they had not signed the treaties.[50] The Court further reasoned that because the tribes were able to use customary fishing sites before white settlers encroached on their lands, the fishing clause—as a reservation of the fishing rights the tribes had historically held—impliedly guaranteed the tribes the right to enter and occupy privately held lands to the extent necessary to fish at customary sites.[51] Thus, the brothers could neither use nor exclusively control fishing wheels at the site because the devices prevented any Yakima fisherman from fishing at the site.[52]

This decision suggested that the fishing clause might impliedly guarantee the tribes other rights necessary for catching fish. Put another way, the right to fish requires having fish to catch, not just having the opportunity to try. Despite this victory for tribes, the Court also included the cryptic remark that the treaty language does not “restrain the State unreasonably, if at all, in the regulation of the right.”[53] Thus, the stage was set for further conflict over the limits of the state’s regulatory authority to control access to the fishing resource. Therefore, through this language, the Court encouraged the following question: whether treaty rights could be subject to reasonable state regulation. The reasonableness of regulations is measured by their relationship to the conservation of the fishery and by the extent to which they impinge on the capacity of tribal members to exercise the rights guaranteed by the treaty. This tension is the hinge on which an effort at co-management would pivot.

Rejecting the premise that the tribes ever had sovereignty or true title to land, the court in State v. Towessnute diverged from the Winans Court by not viewing the fishing clause as a reservation of rights historically held by the tribes.[54] In Towessnute, the Washington Supreme Court sought to limit the fishing rights granted by the Winans holding.[55] In the Towessnute case, the State charged a Yakima fisherman with “off-reservation fishing without a license in a manner forbidden by state law,” and the fisherman argued that he was merely exercising the fishing rights granted to him by the Treaties.[56] Interpreting the treaty as a benevolent “provision from [the United States,] the great guardian of this tribe,” the court first noted that the preservation of customary fishing sites was not essential to the tribes’ survival because the tribes also received land reservations.[57] The court then reasoned that, based on the words “in common . . . with all citizens of the Territory,” the tribes must have recognized that white men would use and potentially exhaust their customary fishing sites.[58] The court further opined that the tribes were aware that they were subject to the state’s criminal laws when signing the Treaties and thus knew they could not “forever . . . fish . . . ignoring regulations.”[59] The court thus held that the tribes only held easements allowing them to access customary fishing sites, in accordance with Winans, and did not possess further rights granting them an exception from state criminal laws and regulations restricting fishing.[60] In the wake of Towessnute, Washington “steadily” passed laws that placed more and more restraints on tribal fishing rights well into the late 1900s.[61] Rather than attempting to reach a mutually agreeable understanding, the State attempted a piecemeal repeal of the treaty through state regulations.

In the 1941 Washington v. Tulee decision, the Washington Supreme Court relied on Towessnute to affirm the conviction of a Yakima fisherman for fishing without a state license.[62] However, the United States Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s judgment, holding that:

[W]hile the treaty leaves the state with power to impose on Indians equally with others such restrictions of a purely regulatory nature concerning the time and manner of fishing outside the reservation as are necessary for the conservation of fish, it forecloses the state from charging the Indians a [licensing] fee of the kind in question here.[63]After noting that Winans held that the Treaties’ fishing clause bestowed continuing rights upon the tribes, the Court reasoned that it had a responsibility of interpreting the clause as the tribes understood it—as a preservation of the right to “fish in accordance with the immemorial customs of their tribes.”[64] The Court reasoned further that imposing a licensing fee was not necessary to conserve fish and instead charged Indians “for exercising the . . . right their ancestors intended to reserve.”[65]

Regardless of the U.S. Supreme Court’s reaffirmation of tribal rights under the fishing clause, Washington continued to restrict and enforce injunctions against off-reservation tribal fishing at customary sites.[66] For example, in the 1968 case Puyallup I, the Washington Department of Game sought declaratory and injunctive relief against “certain fishing” by the Puyallup and Nisqually tribes.[67] Without contradicting its previous decision in Tulee, the Supreme Court upheld the states’ right to regulate the “manner and purpose” of tribal fishing in the interest of conservation, reasoning that the treaties preserved tribal rights to fish in the “usual and accustomed places,” not manner.[68] This regulation reflected the State’s interests in conserving the resource and maximizing the fish available to all parties. In the aftermath of Puyallup I, the Washington Department of Game maintained a statewide “total prohibition of net fishing for steelhead trout.”[69] The regulation of net fishing had to be tied directly to the conservation of the resource. The force of the treaty was restricted to apportionment of the available fish, “but neither the state nor the tribe had the right to eliminate all available fish in any particular run.”

In 1970, the United States reacted to Washington’s tribal-fishing restrictions by filing a lawsuit against the State of Washington on its own behalf and as trustee for the tribes. The United States sought declaratory and injunctive relief against the State of Washington to enforce off-reservation tribal fishing rights.[70] Before the district court issued an opinion in Washington I, the tide again turned. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the tribes in a follow-up case to Puyallup I, holding that the Washington Department of Game’s prohibition of net fishing constituted discrimination against the tribes “because all Indian net fishing is barred and only hook-and-line fishing, entirely pre-empted by non-Indians, is allowed.”[71]

Realizing the complexity of the fishing clause issue, the judge overseeing Washington I, Judge Boldt, split the case into two portions—Phase I and Phase II—hoping “to determine every issue of fact and law presented and, at long last, thereby finally settle . . . as many as possible of the divisive problems of treaty right fishing which for so long have plagued all of the citizens of this area, and still do.”[72] In Phase I, following Winans and diverging from Towessnute, the court observed that tribes reserved previously held rights and did not gain new rights from the treaties.[73] Thus, noting how much tribes had focused on fishing for traditional ceremonies and personal subsistence at the time of the Treaties’ signing, the court held that the Treaties guaranteed that tribal members could use as many fish as needed for these traditional purposes.[74]

The court further held that the Treaties granted commercial tribal fisherman the opportunity to take up to 50 percent of harvestable fish. The court defined harvestable fish as the number of fish that can be commercially harvested without endangering the fish population, not including the fish required for tribal ceremonies and subsistence.[75] The court reasoned that the words “in common” mean “sharing equally” and described a roughly even apportionment of fish between tribal and non-tribal commercial fisherman.[76]

In Washington v. Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Association, the Supreme Court expressed support for Boldt’s holding that the tribes had a right to a maximum of 50 percent of the fish population.[77] The Fishing Vessel Court determined that the exact percentage of the fish population belonging to the tribes would depend on how much is “necessary to provide the Indians with a livelihood—that is to say, a moderate living.”[78] This decision created an implied restriction on tribal take (the yearly amount of fish harvested by the tribe or tribal members) that was not associated with any reasonable regulation tied to resource conservation. Moreover, this litigation reflected both the resentment between the state and the tribes and the difficulty of resolving resource claims without turning every dispute into a zero-sum game.

Obligations on the State: The Implied Environmental Content of the Treaty

The recitation of the cases in the Stevens Treaties litigation gets us to this point: the Treaties created a way to measure and enforce rights held by the tribes, but the rights are not limitless. Importantly, both parties to the treaty-created relationship are limited. Enacting state regulations to conserve resources also suggests that the state must manage activities to benefit treaty beneficiaries and non-Indian residents. This Part explores the genesis of state obligations to manage resources in the interest of both tribes and non-tribal citizens. This Part also considers whether tribes may intervene in state decision-making that indirectly impacts treaty-protected resources. This Part also shows why preempting conflict through co-management will produce better results than litigation. This is likely to be true even if, or perhaps especially if, bargaining is done in the shadow of litigation. This Part explores the correlative rights and duties of the parties.

The Foundation of the State’s Environmental Duty

This litigation encouraged consideration of the precise scope of the rights secured by treaties. However, defining the scope of the rights proved difficult, and the question of whether states were obligated to protect habitats in order to ensure that tribes’ right to fish was meaningful was left unanswered. Based on the Court’s decision that tribes had the right to fish and not just a right to attempt fishing, it naturally followed that states should justify any actions that resulted in fish stock depletion.[79]

In Phase II of the United States v. State of Washington litigation, the district court addressed two major issues: (1) the hatchery issue and (2) the environmental issue. The hatchery issue considered whether the number of harvestable fish includes hatchery-bred fish, while the environmental issue concerned whether the tribes’ right to take fish implicitly includes the right to protect the fish from human-inflicted habitat degradation.[80] On the hatchery issue, the court reasoned that the Treaties’ intent was to “guarantee the tribes [a right to] an adequate supply of fish,” and that right would be jeopardized if the tribes’ share did not include hatchery fish.[81] The court noted that environmental degradation was causing natural fish populations to decline, so hatchery fish—which the state had introduced to compensate for this decline—comprised an ever-increasing percentage of the fish population.[82] Further, the court reasoned that the Treaties included no limitations on the tribes’ fish supply other than the right of non-tribal fisherman to fish “in common” with the tribes.[83] Therefore, the court found no basis for restricting what fish were included in the tribes’ allocation based on “the species or origin of the fish” and issued a declaratory judgment holding that the tribes’ allocation includes hatchery-bred fish.[84]

While the determination that the total quantity of fish necessarily included hatchery-bred fish was important, the more important decision involved the environmental issue. In its declaratory judgment, the court held that the Treaties implicitly imposed a duty on the states to protect fish habitats because the right to fish would be meaningless without the existence of a fish-sustaining habitat.[85] In an en banc hearing, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s holding on hatchery-bred fish, noting that excluding hatchery fish from the tribal allocation would be akin to making the tribes “bear the full burden of the decline [in natural-bred fish populations] caused by their non-Indian neighbors.”[86]

Regrettably, the Court of Appeals vacated the lower court’s judgment on the environmental issue, holding that the lower court abused its discretion by resolving the issue in a declaratory judgment because it was uncertain how other courts would apply the judgment.[87] The Court of Appeals resisted recognizing the tribes’ general environmental right despite that right’s derivation from a specific treaty guarantee.

The Ninth Circuit reasoned that it could not announce general legal standards defining the scope of the environmental right because the obligations that such a right would impose upon Washington would depend on the “concrete facts which underlie a dispute in a particular case.”[88] The court then suggested that it was open to future litigation on the extent of the state’s obligation and noted that “Washington is bound by the treaty.”[89] The court was willing to recognize that the treaty gave the tribes an environmental right, but it was unwilling to impose an open-ended obligation on the state. The tribes now knew they could contest state actions if they could show the actions harmed the fish population.

Habit Protection: Implied Servitudes?

Rather than inviting the tribes to work with the state to devise rules for protecting fish, the decision left the parties to, again, settle the dispute through litigation. In 2001, the issue of whether the state has an independent obligation to consider the effect of actions that have a deleterious impact on fish resurfaced. The tribes filed a Request for Determination[90] on whether Washington had a duty “to refrain from constructing and maintaining culverts under State roads that degrade fish habitat so that [the] adult fish production is reduced.”[91] The United States joined the tribes’ request and sought a permanent injunction requiring Washington to modify or replace culverts that “degrade appreciably” fish movement, particularly the movement of anadromous fish such as salmon.[92] Anadromous fish migrate first from fresh water to the ocean to mature, and then back to fresh water to spawn. Disrupting the migration process depletes the fish stock; culverts are responsible for disrupting fish migrations.

At the time of this litigation, many Washington roads crossed migratory streams, and culverts were used to allow streams to pass under these roads.[93] However, while the culverts provided for the movement of water, some also prevented the passage of fish, hindering the migration and spawning of anadromous fish, and therefore reducing the fish population.[94] Various Washington agencies had constructed and maintained these “barrier culverts” without considering how they impacted the fish population.[95] The tribes maintained that, in service of the Treaties, the state could not ignore the impact these culverts had on fish stocks.

In response to the Request for Determination, Washington argued that the treaties imposed no environmental right and attempted to shift responsibility for potential violations to the federal government.[96] Washington argued that the culverts were part of transportation projects that complied with federal standards. Furthermore, the state argued that because the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) funded the projects, the projects must have been authorized by the Treaties.[97] It further alleged that the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (WSDNR) had consulted with the federal government in developing a fifteen-year schedule for the remediation of fish problems on forest roads. The state’s arguments relied on the incorrect premise that the federal government’s failure to reject these transportation project plans necessarily meant that the plan was consistent with the Treaties.[98] Washington was confident that these barrier culverts were lawful because federal agencies approved the permits for their construction.[99]

Based on these allegedly misleading actions of the federal government, Washington asserted a “waiver and/or estoppel” defense.[100] According to Washington, because the state relied on the federal government’s approval of the barrier culverts, the federal government was thereby precluded from arguing that those same culverts violated the Treaties. Washington also argued that the federal government was placing an “unfair burden” upon it by restricting Washington’s usage of barrier culverts when the federal government and the tribes had also built barrier culverts in the area protected by the Treaties.[101] Based on this argument, Washington made a cross-request[102] that the federal government modify or replace its own barrier culverts, but the district court dismissed both this request and Washington’s request to amend it, holding that the United States had—and did not waive—sovereign immunity and that Washington lacked standing to seek redress for the tribes’ injuries.[103]

The district court was unpersuaded by Washington’s argument and ultimately found the state had an implied duty to maintain the fish population. The district court granted summary judgment on the tribes’ and United States’ requests, holding that the fishing clause did impose a duty upon Washington to avoid building and using culverts that reduce the fish population and that Washington was violating this duty.[104] After a bench trial on remedies, the court issued a Memorandum and Decision noting that Stevens Treaties negotiators had “assured the Tribes of their continued access to their usual fisheries” and that habitat destruction significantly impedes tribes’ ability to exercise their right to fish.[105] The court also issued a permanent injunction ordering Washington to list its barrier culverts within the treaty area and Washington agencies to modify their barrier culverts to avoid hindering fish movement.[106] The court’s ruling resulted in an implied duty that reinforced the obligations that Washington owed to the tribes.

Washington appealed the decision, raising a number of objections, including (1) the holding that the Stevens Treaties conferred environmental rights, (2) the overruling of the waiver defense, and (3) the dismissal of its cross-request and the injunction.[107] Examining the first objection, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found that Washington III did not preclude it from evaluating whether the state had implied environmental obligations. The court measured Washington’s treaty duties on the basis of “all the facts presented by a particular dispute.”[108] The court noted that it had a duty to construe the Treaties as the tribal signees would have and “as justice and reason demand.”[109] The court held that it should read the treaties in a way that effectuates the tribes’ goal of ensuring an adequate fish supply.[110]

In a startling claim made during oral argument, the state’s lawyer asserted that Washington was not obligated to ensure that there were any fish at all.[111] According to the state, Washington could deplete the fish supply through habitat degradation without violating the Treaty.[112] Judge Fletcher of the Ninth Circuit disagreed. In accordance with Washington III, the court examined the specific facts of the case and found that the culverts reduced the supply of harvestable fish by several hundred thousand.[113] Relying on language from Fishing Vessel, the court found that the reduced fish supply was inadequate to guarantee the tribes a “moderate living,” due to both the burden placed on individual tribal fisherman to earn a living and the overall detriment to tribal economics.[114] While the initial imposition of a limitation based on whether the catch guaranteed a “moderate living” was a deviation from the plain reading of the treaty guarantees, that standard was used to impose a broad environmental obligation on the state.

Moreover, the court rejected Washington’s waiver argument, holding that FHA approval of the culvert projects did not weaken any treaty rights, including the environmental right.[115] The court reasoned that, just as the United States “cannot, based on laches or estoppel, diminish or render unenforceable otherwise valid Indian treaty rights,” the United States cannot waive treaty rights.[116]

Washington also complained that the court’s injunction was overbroad. The state claimed that the evidence was inadequate to show that all state-owned barrier culverts significantly contributed to the decline of fish populations. In response, the Ninth Circuit noted that the tribes presented data showing that the salmon population could increase by 200,000 annually if the state modified its culverts.[117]

Further, Washington argued that modification of state-owned culverts would have little beneficial effect because of non-state-owned barrier culverts that would still prevent fish migration.[118] The court rejected this argument because many non-state-owned culverts were either further upstream than state culverts or were constructed to allow the partial passage of fish.[119] The Ninth Circuit also rejected Washington’s contention that the injunction required it to correct “nearly every state-owned barrier culvert” without considering that some culverts had minor effects on fish populations, noting that the injunction gave the state additional time to correct “low-priority” culverts that had a minor impact on fish habitats.[120]

Washington further argued that the district court did not appropriately defer to the state’s expertise. Washington alleged that, by focusing the injunction solely on culverts, the court ignored the state’s expert testimony that a comprehensive strategy would most effectively preserve and restore salmon population.[121] However, the Ninth Circuit held that it was appropriate for the injunction to only address the culvert issue, as that was the only alleged treaty violation and was a primary cause of habitat degradation.[122]

In the face of this, Washington argued that the appellate court did not appropriately consider costs and equitable principles in issuing its injunction.[123] However, the Ninth Circuit found errors in Washington’s calculations of costs and noted that Washington would receive some funding for the culverts from the federal government.[124] The court further noted that, based on federal and state law, Washington would have been required to correct its culverts without the injunction; the injunction only required the correction to occur sooner than it otherwise would have.[125] The Ninth Circuit pointed out that the district court had considered equitable principles and found that “[t]he balance of hardships tips steeply toward the Tribes.”[126]

Washington’s final objection to the injunction was that it “impermissibly and significantly intrudes into state government operations” and violates federalism principles.[127] Washington based this argument on the contention that it was already making adequate progress towards correcting culverts and would unnecessarily have to divert resources from other important state programs based on the injunction.[128] However, the Ninth Circuit found that the state had not been making adequate progress in correcting its culverts and that Washington should use its transportation budget to do so rather than cut into its budget for other programs.[129] The Ninth Circuit found the federalism objection invalid, noting that state governments receive less deference in the context of fulfilling tribal treaty obligations.[130]

The court’s clear rejection of each of the state’s arguments indicates that the Treaties impose an obligation on the federal government to act as a trustee for tribes. Part of this obligation requires state governments to both understand and comply with the Treaties’ terms. The state may not push its obligations off onto the federal government, nor may it pretend to be blind to the impacts of its decision-making on treaty-protected resources. The court made it clear that when a state makes decisions that have even an indirect impact on a treaty-protected resource, the state must provide evidence that it fully considered those impacts and determined that they were sufficiently attenuated or de minimis before proceeding.

The Supreme Court and the Range of Environmental Duties

Demonstrating the tangible impact of the Stevens Treaties litigation, Washington moved forward with correcting its culverts and continues to implement measures demanded by the injunction.[131] An equally divided Supreme Court affirmed the Ninth Circuit’s Court of Appeals’ holding in Washington v. United States without issuing an opinion.[132] Thus, the Ninth Circuit’s strongly reasoned opinion, especially Judge Fletcher’s position, remains binding law. Perhaps Washington was most troubled by the court’s reasoning because it raised the possibility of tribes asking the court to enjoin the state from committing other types of environmental harms.[133]

Washington was quite explicit about this fear: in its argument before the Supreme Court, it maintained that “the treaties become a catch-all environmental statute that will regulate every significant activity in the Northwest . . . .”[134] The Washington case suggests that if the tribes have “concrete facts” showing that state actions significantly contribute to fish-habitat destruction, courts might be willing to enjoin those actions. For example, with the increasing availability of science connecting air pollution to climate change and climate change to salmon habitat degradation, the tribes could potentially seek to enjoin state activities that cause air pollution.[135] The primary issue the tribes might face when bringing such cases would be showing that the actions at issue are a significant enough cause of the habitat destruction.[136]

Washington v. United States resulted in the state being enjoined from committing at least one type of environmental degradation. While the court left the door open for enjoining different types of environmental degradation, this is still unlikely to restore tribal fishermen’s ability to earn a moderate living because the salmon fisheries have been degraded by multiple sources, not just culverts.[137] However, we can hope for a future with a broader interpretation of tribal fishing rights and the environmental duties implicit in those rights.

The promise of this decision is that the tribes will have additional say in decisions that affect the shared resources that are protected by treaties. However, Washington’s argument that this decision is overbroad is unfounded. While Washington speculates that the Ninth Circuit’s decision creates a catchall for environmental duties, that is unlikely. The decision’s reach is cabined by the need for a specific, articulable scientific link between the state’s conduct and habitat degradation. In its argument before the Supreme Court, the state speculated that the Ninth Circuit’s decision created a free-floating environmental duty, but the necessary link between the science of habitat degradation and the actions of the state foreclose this reading. Perhaps more importantly, the case has given rise to institutional innovation as both the state and the tribes work to address the problem in a way that might build a model for environmental cooperation.

Co-management Agreements

This Essay began by referencing the groundbreaking agreement between the federal government and the tribes in the creation of the Bears Ears National Monument. As recent events have illustrated, these kinds of agreements are unstable if they are not rooted in a property regime that is binding on all parties. Binding both parties to an agreement limits the capacity of one side to make unilateral changes. While this Essay will not speculate on the outcome of the ongoing Bears Ears litigation, the kinds of co-management agreements seen in the fishing context differ in significant ways.

First, the negotiations of the co-management agreements are done in the shadows of both the federal courts’ supervision as well as the Treaties. The framework provided by the Treaties and the treaty litigation provides each side with an understanding of the contours of the property regime that ought to guide a management decision. As early as 2003, the Property and Environment Research Center, which describes itself as the home of free-market environmentalism, noted that a clear expression of property rights arising out of treaties could create a framework for an agreement that benefits all parties.[138] This work recognized that property rights create boundaries that limit what each side may demand. These property limitations arise in both private and public law and create real barriers to arbitrary public or private action.[139]

Second, such agreements respect the natural limitations on parties’ actions regarding maintenance of treaty-protected resources. The tribes and states both bring perspectives to the table that inform how parties’ obligations ought to be structured. Finally, because these agreements are negotiable for short terms, there can be a kind of rolling experimentation with institutional design. This experimentation creates a decision-making and adjudicatory flexibility that permits adjustments in the face of new knowledge and as goodwill is developed out of good faith negotiation.

Negotiation of co-management agreements is a hard road because the states have been relatively intransigent. Because the federal courts have staked out the boundaries of the treaty obligations and the most outlandish positions of the states have been abandoned, the property regimes that emerge will reflect this hard-won knowledge. Complications arising from climate disruption certainly raise the stakes, but this century-long trail of litigation has lasting value because it considered the institutional arrangements that permit both sides to adjust to emerging realities.

Conclusion

I reviewed fifteen co-management agreements to determine whether there were lessons that could be learned from existing agreements and to determine the effects of persistent litigation on the structure of those agreements.[140] I can make a few generalizations based on this review. First, establishing the boundaries of treaty or litigation-based property rights was paramount, so much so that the agreements were careful to state areas of continued disagreement and to preserve rights to litigate. Second, the tribes were also careful to insist on the sovereign status of the tribes and to claim all the protections such a status might entail. Any resource management agreement was not an abridgement of that status but was an act taken consistent with it. Such insistence was especially clear when the agreement was with a subdivision of the state or with a local authority. The co-management agreements might usefully be understood as signposts on a new path towards sovereign cooperation.

All the co-management agreements are steps towards changing the colonial relationship that has dominated federal and state policy. When President Nixon declared the era of termination over and welcomed the birth of a new period of self-determination, his declaration did not signal the end of the struggle for a more autonomous scope of action for tribes.[141] To the contrary, ending the era of termination marked the beginning of a period that required states to adjust to a new era of government-to-government relations. Though states would continue to resist tribal sovereignty, they would no longer be able to rely on the federal government as their constant ally.

As illustrated in this Essay, the struggle for tribal sovereignty worthy of the name continues to this day. Nonetheless, tribes and non-tribal actors have recognized that bargaining in the shadow of the law[142] is a step towards recognizing the mutual needs of parties, so long as they can create strong boundaries premised on fundamental sovereign claims. Where there are treaties, the claims are capable of clear expression. The fights at the margins, where disputes over treaty guarantees remain, are unlikely to reduce the costs to the states. Importantly, as in the case of resource management, the express words of the treaties are often the starting point. The purpose of the treaties and the tribes’ understanding at the time the treaties were adopted are the lodestars for interpreting the parties’ obligations. How those obligations will be expressed and how differences will be resolved are the questions that are at the heart of the negotiations.

Only by recognizing the legal and ethical bankruptcy of resisting the end of a colonial relationship with tribes can states move forward and accomplish two important things. First, by recognizing the validity of the treaty claims and the correlative rights necessary to achieve the purposes of the treaties, the costs of litigation can be reduced, if not eliminated. The parties can also design procedures that balance sovereign claims. Second, rather than understanding the decision as one in which the states lose by having to redesign their administrative procedures to account for treaty obligations, the states and the tribes should recognize that the mutuality of resource protection creates obligations on both sides. This means that designing resource-protection procedures can induce the tribes to undertake actions that have potential long-term benefit to both tribes and non-Indians.

This does not intend to oversimplify the decolonization of American Indian law, but the litigation demonstrates that “[t]he question of rights and justice for Indigenous peoples is concerned not only with the distribution of resources but also with the ‘capability’ of the resources to fulfill the well-being of a people.”[143] The conflict over resources is also a conflict over the fundamental relationship between tribal and non-tribal people. As Professor Curley put it when recounting a conflict over water rights:

The proposed water settlement produced contradictory logics, practices, and frameworks that combined two “traditions of Indigenous resistance,” one rooted in the language of self-determination and sovereignty and the other in emerging notions of decolonization. This hybridity of seeking increased water recognition within colonial law, while advocating for decolonial waterscapes, speaks to the complicated and fundamentally entangled political landscapes of Indigenous peoples.[144]

Untangling the history of colonization and braiding in a commitment to mutual respect and self-determination is what the litigation over treaty resource rights is really about. Litigation concerning treaty-protected resources involves the seemingly perpetual conflict between tribal and non-tribal people. Zero-sum conflict fundamentally misunderstands what is at stake. Tribes and states must co-exist. Working out a relationship that does not merely replicate the history of tribal oppression, but which can make a space for both governments to assert their rightful role in managing crucial resources, is not just politically sensible but economically sensible as well. Studying the history of this litigation shows that judicial resolution of conflict is one way, but perhaps not the best way, to resolve these disputes and begin to put the dismal history of colonialism behind us.

Appendix

Appendix

Figures 1 & 2. Excessive water drop and high velocity water flow impedes or blocks fish migration. © Jerilyn Walley/South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Figures 1 & 2. Excessive water drop and high velocity water flow impedes or blocks fish migration. © Jerilyn Walley/South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

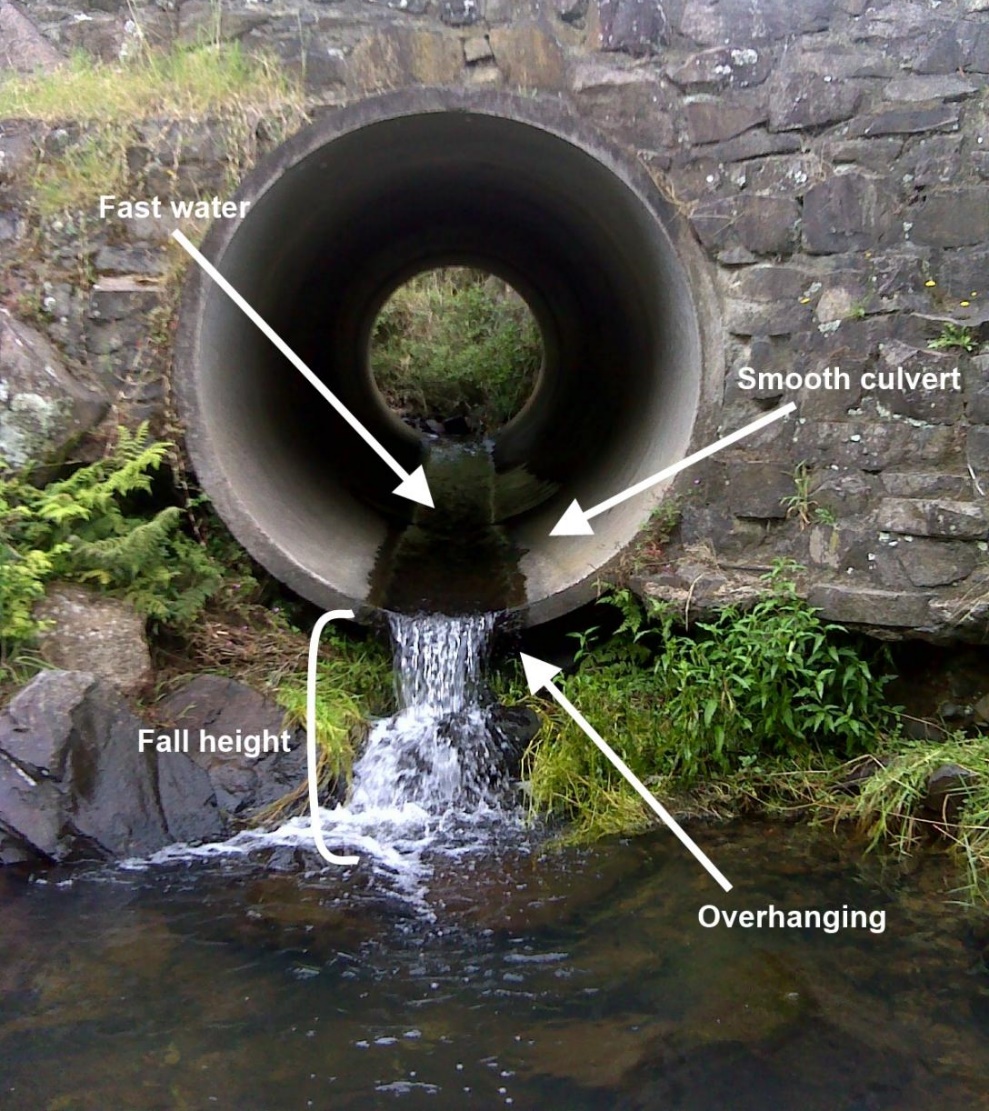

Figure 3. Example of some of the key features that can impede fish passage at culverts. © Dr. Paul Franklin.

- Professor of Environmental Justice, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and Associated Professor, Yale Law School. ↑

- . Charles Wilkinson, “At Bears Ears We Can Hear the Voices of Our Ancestors in Every Canyon and on Every Mesa Top”: The Creation of the First Native National Monument, 50 Ariz. St. L.J. 317 (2018). ↑

- . Professor Sax, in his ground-breaking article, anticipates many of these arguments. See Joseph L. Sax, Takings, Private Property and Public Rights, 81 Yale L.J. 149 (1971) (discussing the ways that spillover effects have to be understood and accommodated within a private property regime with a properly functioning regulatory system). ↑

- . The Northwest Ordinance mentions Indians twice, once in Section 8 and again in Article III. Perhaps the language of Article III captures it best:The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in their property, rights, and liberty they never shall be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity shall, from time to time, be made, for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace and friendship with them.Northwest Ordinance of 1787, ch. 8, 1 stat. 50, 52 (1789) (reaffirming an ordinance created by the Confederation Congress, An Ordinance for the Government Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio (July 13, 1787)). The Non-Intercourse Act was designed to protect Indian land by requiring ratification of private purchases by Congress. Non-Intercourse Act, ch. 33 1 Stat. 137 (current version at 25 U.S.C. § 177 (2018)). ↑

- . Antiquities Act of 1906, Pub. L. No. 59-209, 34 Stat. 225 (current version at 54 U.S.C. §§ 320301–320303 (2018)). ↑

- . For a discussion of the process, see Grand Canyon Trust, www.grandcanyontrust.org (last visited July 29, 2019) [https://perma.cc/BU6K-BVFF]. For more specific information about the inter-tribal coalition, see Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, https://bearsearscoalition.org/ (last visited Jan. 30, 2020) [https://perma.cc/ 9N7B-XUGG]. ↑

- . “Traditional knowledge” is often a fraught term, and Professor Wilkinson described the use of that term instead of the more common “traditional ecological knowledge” (TEK). For Professor Wilkinson’s description of the process and the substantive impact of the tribes, see Wilkinson, supra note 1, at 321–22, 326–27, 329–32. See also Anthony Moffa, Traditional Ecological Rulemaking, 35 Stan. Envtl. L.J. 101, 105–12 (2016). Moffa provides the leading definitions of TEK as “unique, traditional, local knowledge, existing within and developed around the specific conditions of women and men indigenous to a particular geographic area,” id. at 106 (quoting Louise Grenier, Working with Indigenous Knowledge: A Guide for Researchers 1 (1998)), or “a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living being (including humans) with one another and with their environment.” Id. at 107 (quoting Fikret Berkes, Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management 8 (1999)). ↑

- . Glossary of Statistical Terms, OECD, https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail .asp?ID=382 (last updated Nov. 2, 2001) [https://perma.cc/WA64-DE3L]. ↑

- . Lars Carlsson & Fikret Berkes, Co-management: Concepts and Methodological Implications, 75 J. Envtl. Mgmt. 65 (2005). Carlsson and Fikret suggest “co-management . . . should be understood as a continuous problem-solving process” as they detail the various attempts to categorize the formal arrangement. Id. at 65. ↑

- . For example, a recent Supreme Court decision held that the admission of Wyoming to statehood did not automatically terminate treaty obligations that restrained state enforcement of hunting and fishing regulations. Herrera v. Wyoming, 139 S. Ct. 1686, 1694 (2019). ↑

- . Id. at 1694; see also Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, 526 U.S. 172 (1999) (holding that the tribe retained usufructuary rights over lands that they had ceded to the federal government and implicitly overruling Ward v. Race Horse, 163 U.S. 504 (1896), which had extinguished certain treaty rights of the Bannock tribe upon the admission of Wyoming to the Union). ↑

- . Act of Mar. 3, 1871, ch. 120, 16 Stat. 544 (codified as amended 25 U.S.C. § 71 (2018)). ↑

- . This is exactly the controversy that was only partially resolved in Ward v. Race Horse and the controversy the State of Wisconsin asserted in the case of Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States, 391 U.S. 404 (1968), where the Supreme Court held that the treaty rights survived the termination of the tribe under federal law. ↑

- . The characterization of the tribes’ unique political status was first articulated by Justice Marshall in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1, 17 (1831). ↑

- . Washington v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 1832, 1833 (2018). ↑

- . The explosion in private law theory, largely associated with questions of contract and tort theory, often take as their starting point whether the existing rules distort results parties might have achieved through negotiation. As Professor Coleman put it:The primary aim of law is to regulate conduct through norms—usually rules—that create reasons, grounds, or warrants for action. Many of these reasons take the form of rights, privileges, and liberties on the one hand, and duties and other encumbrances on the other. Arguably, both the laws of tort and crime impose duties or prohibitions on agents, whereas the law of contract confers powers on individuals to create legally enforceable rights and duties.Jules Coleman, The Costs of the Costs of Accidents, 64 Md. L. Rev. 337, 337 (2005). ↑

- . Fronda Woods, Who’s in Charge of Fishing, 106 Or. Hist. Q. 412, 415 (2005). While taking the perspective of the state, this justly celebrated article tracks the more than hundred-year history of the conflict in state and federal courts over the resources claimed by the tribes and the right they claim to use them free from state interference. See also Michael C. Blumm, Indian Treaty Fishing Rights and the Environment: Affirming the Right to Habitat Protection and Restoration, 92 Wash. L. Rev. 1 (2017). ↑

- . Kent Richards, The Stevens Treaties of 1854–1855, 106 Or. Hist. Q. 342, 346 (2005). ↑

- . All of the Stevens Treaties contained this basic promise:The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians, in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing, together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on open and unclaimed lands . . . .Treaty of Medicine Creek, art. III, Dec. 26, 1854, 10 Stat. 1132, 1133; see, e.g., Point Elliott Treaty, art. V, Jan. 22, 1855, 12 Stat. 928; Point No Point Treaty, art. IV, Jan. 26, 1855, 12 Stat. 934; Makah Treaty, art. IV, Jan. 31, 1855, 12 Stat. 940; Walla Walla Treaty, art. I, Jun. 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 946; Yakama Treaty, art. III, ¶ 2, Jun. 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 951; Nez Perce Treaty, art. III, ¶ 2, Jun. 11, 1855, 12 Stat. 958; Middle Oregon Treaty, art. I, ¶ 3, Jun. 25, 1855, 12 Stat. 963; Treaty of Olympia, art. III, Jan. 6, 1856, 12 Stat. 972; Flathead Treaty, art. III, ¶ 2, July 16, 1855, 12 Stat. 975. ↑

- . See Blumm, supra note 16 and the cases collected therein. ↑

- . See, e.g., Yurok Tribe v. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 231 F. Supp. 3d 450 (N.D. Cal 2017). The issues raised in this case are exemplary of the struggle caused by droughts in the West and the increasing unreliability of water. See also Holly Doremus, Water War in the Klamath Basin: Macho Law, Combat Biology, and Dirty Politics (2d ed. 2008) (detailing the long and involved conflict over the management of the Klamath River). ↑

- . A report by the State of Washington bluntly stated: “Climate-related changes, such as warmer temperatures and a change in the chemistry of our oceans, will threaten our shellfish.” Impacts on Shellfish – Climate Change, Wash. St. Dep’t Health, https://www.doh.wa.gov/CommunityandEnvironment/Climateand Health/Shellfish (last visited Sept. 3, 2019) [https://perma.cc/VN9U-VNSB]. ↑

- . The so-called Marshall Trilogy—Johnson v. M’Intosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823), Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), and Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832)—created the framework that initially guided the development of federal Indian law. Of course, the various European colonists took differing tacks. See Anthony Pagden, Lords of all the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain, and France c. 1500–c. 1800 (1995). ↑

- . Article IX of the Articles of Confederation maintained, inter alia, that “[t]he United States in Congress assembled shall also have the sole and exclusive right and power of . . . regulating the trade and managing all affairs with the Indians, not members of any of the States, provided that the legislative right of any State within its own limits be not infringed or violated . . . .” Articles of Confederation of 1781, art. IX. ↑

- . Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903). ↑

- . See, e.g., David Treuer, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present (2019) (describing the massacre at Wounded Knee, commonly thought of as the end of tribal martial resistance, but suggesting that the last significant battle occurred in 1918). ↑

- . See, e.g., Alyosha Goldstein, By Force of Expectation: Colonization, Public Lands, and the Property Relation, 65 UCLA L. Rev. Discourse 124 (2018) (analyzing the case of Cliven Bundy and the occupation of a federal wildlife refuge as the paradigmatic instance of this conflict). ↑

- . As suggested previously, “Indian Country” is a technical term defined in 18 U.S.C. § 1151 (2018). It includes land within the boundaries of the reservation (unless clearly diminished by Congress), as well as allotments and dependent Indian communities outside of the boundaries of reservation. It also includes retained easements over public and private land. ↑

- . See Winans v. U.S., 198 U.S. 371, 379 (1905). The position that this was only a private dispute that could be resolved by reference to ordinary trespass law was first raised in the Winans case and despite the rejection of this theory by the Supreme Court has, nonetheless, been repeated consistently in subsequent fishing litigation. ↑

- . Woods, supra note 16, at 417. ↑

- . 163 U.S. 504, 506 (1896). ↑

- . 526 U.S. 172, 206–07 (1999). ↑

- . Herrera v. Wyoming, 139 S. Ct. 1686, 1697 (2019). ↑

- . In some ways, this is a modern statement of the relationship first articulated in Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832), which stood for the proposition (now much compromised by various exceptions and limitations) that there were only two sovereign powers operative on treaty-protected land: the federal government and the tribe. ↑

- . For example, the ten treaties that are included under the heading of the Stevens Treaties were concluded by the mid-1850s, but Washington State did not enter the Union until 1889. Oregon became a state in 1859 some four years after the conclusion of the Stevens Treaties. ↑

- . See Francis Paul Prucha, American Indian Treaties: The History of A Political Anomaly (1994). ↑

- . See U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 2. ↑

- . See Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, 526 U.S. 172 (1999). ↑

- . It was the discovery of gold in Cherokee country that led the State of Georgia to assert jurisdiction over the Indian territory in the state, prompting the Cherokee to initiate the case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831). But the largest loss of tribal land and resources began with the passage of the Dawes Act (also known as the General Allotment Act of 1887), through which the tribes lost over 100 million acres of land, or about two-thirds of their land base, before 1887. General Allotment Act (Dawes Act), 24 Stat. 388 (1887), repealed by the Indian Consolidation Act Amendments of 2000, Pub. L. No. 106-462, 114 Stat. 1991. The Dawes Act was emblematic of the processes large and small that gnawed away at tribal resources, principally land, when non-Indians needed or wanted those resources. Equally emblematic is the case of Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903), where the Supreme Court validated the unilateral abrogation of Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 in a manner contrary to the actual terms of the Treaty. The legislation adopted by Congress not only changed the terms of the Treaty but also opened over two million acres of Kiowa land to settlement by non-Indians. ↑

- . Treaty with the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Etc., June 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 945; Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon, June 25, 1855, 12 Stat. 963; Treaty with the Yakima, June 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 951; Treaty with the Nez Perce, June 11, 1855, 12 Stat. 957; Treaty with the Makah, Jan. 31, 1855, 12 Stat. 939; Treaty with the Nisqualli, Puyallup, Etc., Dec. 26, 1854, 10 Stat. 1132; Treaty of Point Elliott, Jan. 22, 1855, 12 Stat. 927; Treaty with the S’Klallam, Jan. 26, 1855, 12 Stat. 933; Treaty with the Quinault, Etc., Jul. 1, 1855, 12 Stat. 971. ↑

- . Ryan Hickey, Highway Culverts, Salmon Runs, and the Stevens Treaties: A Century of Litigating Pacific Northwest Tribal Fishing Rights, 39 Pub. Land & Resources L. Rev. 253, 254 (2018); Vincent Mulier, Recognizing the Full Scope of the Right to Take Fish Under the Stevens Treaties: The History of Fishing Rights Litigation in the Pacific Northwest, 31 Am. Indian L. Rev. 41, 41 (2007). ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d 946, 954 (9th Cir. 2017), cert. granted, 138 S.Ct. 735 (2018), aff’d, 138 S. Ct. 1832 (2018). ↑

- . Hickey, supra note 40, at 264 (quoting Washington v. Wash. State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass’n, 443 U.S. 658, 674 (1979)). ↑

- . Trying to strike that balance is what led to the “moderate living” standard in Washington v. Fishing Vessel Assn., 443 U.S. 658, 686 (1979). ↑

- . See United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 954. One article of the Treaty with the Yakamas guaranteed “[t]he exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams, where running through or bordering said reservation, is further secured to said confederated tribes and bands of Indians, as also the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places, in common with the citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary buildings for curing them; together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses and cattle upon open and unclaimed land.” Treaty with the Yakama, June 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 951. This clause is repeated throughout the various treaties that make up the Stevens Treaties. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 954; Mulier, supra note 40. ↑

- . United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371, 380 (1905) (quoting Washington v. Wash. State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass’n, 443 U.S. 658, 679 (1979)). ↑

- . Winans, 198 U.S. at 379 (emphasis omitted). ↑

- . Id. at 384; Mulier, supra note 40; see also Seufert Bros. Co. v. United States, 249 U.S. 194 (1919) (holding that the Yakimas had such rights under the Treaties not only in Oregon but also in Washington). ↑

- . Winans, 198 U.S. at 381. ↑

- . Id.; Mulier, supra note 40, at 49. ↑

- . Winans, 198 U.S. at 382. ↑

- . Id. at 384. ↑

- . Compare State v. Towessnute, 154 P. 805, 806–07 (1916), with Winans, 198 U.S. at 381. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 956; cf. Hickey, supra note 40, at 257 (“Washington’s state courts consistently read [the Fishing Clause] as narrowly as possible, minimizing tribal fishing rights while expanding State regulatory powers and opportunities for commercial fishermen.”). ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 956. ↑

- . Towessnute, 154 P. at 807. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 807–08. ↑

- . Id. at 808. ↑

- . Hickey, supra note 40, at 258. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d 946, 956–57 (9th Cir. 2017) (discussing the holding and case of Washington v. Tulee, 109 P.2d 280, 287 (1941)). ↑

- . Tulee v. Washington, 315 U.S. 681, 684 (1942) (emphasis added). ↑

- . Id. at 684. ↑

- . Id. at 685. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 957. ↑

- . Puyallup Tribe v. Dep’t of Game of Wash. (Puyallup I), 391 U.S. 392 (1968) (emphasis added). ↑

- . Id. at 398 (emphasis added). ↑

- . Dep’t of Game of Wash. v. Puyallup Tribe (Puyallup II), 414 U.S. 44, 46 (1973). ↑

- . United States v. Washington (Washington I), 384 F. Supp. 312, 327–28 (W.D. Wash. 1974), aff’d and remanded, 520 F.2d 676 (9th Cir. 1975). ↑

- . Puyallup II, 414 U.S. at 48. ↑

- . Washington I, 384 F. Supp. at 330. ↑

- . Mulier, supra note 40, at 62. ↑

- . Washington I, 384 F. Supp. at 343. ↑

- . Id. (emphasis added). This conservation-based restriction on how many fish tribes have the right to take has roots in Puyallup I’s holding that states could regulate fishing in the interest of conservation. ↑

- . Id.; Mulier, supra note 40, at 65. ↑

- . Washington v. Wash. State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass’n, 443 U.S. 658, 686 (1978). ↑

- . Id. (emphasis added). ↑

- . For an early and compelling statement of this reading of the cases, see Blumm, supra note 16. ↑

- . United States v. Washington (Washington II), 506 F. Supp. 187, 190 (W.D. Wash. 1980), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 694 F.2d 1374 (9th Cir. 1982), on reh’g, 759 F.2d 1353 (9th Cir. 1985). ↑

- . Id. at 197–98. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 203–04; Mulier, supra note 40 , at 80. ↑

- . This holding is reminiscent of Winans’s holding that the Treaties impliedly incorporated a right of the tribes to access fish. In general, according to federal Indian law principles, when tribes reserve a right in a treaty, they implicitly reserve access to any resources essential to actualizing that right. Alan Stay, Habitat Protection and Native American Treaty Fishing in the Northwest, Fed. Law., Oct.–Nov. 2016, at 20. ↑

- . United States v. Washington (Washington III), 759 F.2d 1353, 1360 (9th Cir. 1985) (en banc). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 1357. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . This Request for Determination was technically a sub-proceeding of the 1974 case. Jonathan P. Scoll, A (Belated) Win for Tribes and Fish, 32 Nat. Resources & Env’t 64 (2018). ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d 946, 960 (9th Cir. 2017). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Susan Kanzler et al., Wash. Dep’t of Fish & Wildlife, WSDOT Fish Passage Performance Report 33 (2019), https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/sites/default/ files/2019/09/20/Env-StrRest-FishPassageAnnualReport.pdf [https://perma.cc/ G5XJ-ZSUF] (“A list of culverts blocking salmon or steelhead passage within the case area was filed on September 27, 2013, containing 1,014 barriers, including 847 with a significant habitat gain and 167 with a limited habitat gain. As of June 3, 2019, WSDOT has 1,001 culvert barriers relevant to the U.S. v. WA case—817 with significant habitat upstream (≥200 meters) and 184 with a limited habitat gain (>200 meters).”). ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 958. ↑

- . Id. See Appendix for exemplary photographs of the offending culverts. ↑

- . Id. at 960. ↑

- . Id.; Hickey, supra note 40, at 265–66. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 966. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 960. ↑

- . A cross-request is similar to a counterclaim filed in response to a Request for Determination. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 960. ↑

- . Id. at 961. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 962. ↑

- . Id. at 966. ↑

- . Id. at 963. As the Court said in United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371, 380–381 (1905):[W]e will construe a treaty with the Indians as “that unlettered people” understood it, and “as justice and reason demand, in all cases where power is exerted by the strong over those to whom they owe care and protection,” and counterpoise the inequality “by the superior justice” . . . . In other words, the treaty was not a grant of rights to the Indians, but a grant of right from them—a reservation of those not granted. And the form of the instrument and its language was adapted to that purpose. ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 963. ↑

- . Transcript of Oral Argument at 4, United States v. Washington, 138 S. Ct. 1832 (2018) (No. 17-269) (Justice Sotomayor asked the State precisely about this claim: “In the courts below during the argument in the Ninth Circuit, you said the Stevens Treaty would not prohibit Washington from blocking completely every salmon stream into Puget Sound. Basically, the right to take fish, to you, means the right to take fish if you decide you want to provide fish.”). ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 965. ↑

- . Id. at 966. ↑

- . Id. As Judge Fletcher noted:The Court recognized that the Treaties promised that the Tribes would have enough salmon to feed themselves. . . . The Tribes get only fifty percent of the catch even if the supply of salmon is insufficient to provide a moderate living. However, there is nothing in the Court’s opinion that authorizes the State to diminish or eliminate the supply of salmon available for harvest.. . .Our opinion does not hold that the Tribes are entitled to enough salmon to provide a moderate living, irrespective of the circumstances. . . . We hold only that the State violated the Treaties when it acted affirmatively to build roads across salmon bearing streams, with culverts that allowed passage of water but not passage of salmon.United States v. Washington, 864 F.3d 1017, 1020 (9th Cir. 2017) (citation omitted); see also United States v. Washington, 827 F.3d 836, 852 (“Thus, even if Governor Stevens had made no explicit promise, we would infer, as in Winters and Adair, a promise to ‘support the purpose’ of the Treaties. That is, even in the absence of an explicit promise, we would infer a promise that the number of fish would always be sufficient to provide a ‘moderate living’ to the Tribes.” (quoting Washington v. Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass’n, 443 U.S. 658, 686 (1979))). ↑

- . United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d at 966–68. ↑

- . Id. at 967. ↑