The pro bono interests of law firm lawyers tend to differ from the actual legal needs of the poor. This difference results in the mismatch problem or the incongruence between the interests of firm lawyers and the needs of the poor. Today, the mismatch problem has resulted in law firm lawyers’ increased demand of immigration matters while legal needs are greatest in housing and family law. This leaves nonprofit legal services organizations scrambling to find pro bono representation for poor clients or otherwise relying on very limited resources to represent poor clients.

The literature on the mismatch problem is lacking in important ways. First, there is a lack of understanding about how the interests of individual lawyers factor into the selection of pro bono matters. Second, there is no understanding about how law firm culture impacts the choice of pro bono work for firms and individual lawyers. Third, the literature does not include how the political climate impacts the choice of pro bono work within firms. Finally, the literature is devoid of normative suggestions to remedy the problem. Through an interview-based empirical exploration, this research explains how individual lawyers impact the choice of pro bono work, how law firm culture impacts pro bono choices, and how the political climate directly shapes what lawyers choose to do for pro bono legal representation.

To solve the pro bono mismatch, I make three proposals: (1) modification of the language of the American Bar Association’s Model Rule of Professional Conduct 6.1, which provides that lawyers have a professional responsibility to provide pro bono legal services; (2) creation and implementation of macro-level “pay for preference;” and (3) creation and implementation of micro-level “pay for preference” regimes in law firms to nudge lawyers to consider the greatest legal needs in their choices of pro bono legal representation.

Introduction

The pro bono mismatch is an incongruence between the interests of law firms—and their lawyers—and the actual legal needs of the poor. The mismatch is problematic because individuals with the greatest legal needs are often left without legal representation despite the ubiquity of law firm pro bono legal services today. Several legal scholars have recognized some variation of the mismatch problem. Through empirical research of law firms, the literature shows that lawyers “are encouraged to work on pro bono matters that align with their personal interests or expertise and that will provide them with professional development opportunities.”[2] Other scholars have also observed that law firm interests are driven by considerations regarding client conflict, business-creation interests, or other market-focused factors.[3] Firms avoid matters in areas of law in which many nonprofit legal services organizations (NLSOs)[4] seek volunteer lawyers—such as employment law, labor law, and foreclosures—so as not to conflict with their clients’ interests.[5] Firms also avoid matters in family law, except for domestic violence, because such matters are seemingly time consuming[6] and stressful.[7] On the other hand, firms favor pro bono matters with “market appeal”—that is, those in which they can enjoy favorable public relations.[8] These public relations matters are usually large-scale litigations rather than the representation of individual clients.[9] Thus, there is some understanding in the literature that law firms tailor their choice of pro bono matters to avoid client conflict, to reduce time consumption, and to benefit public relations.

Yet the literature is missing important insights. First, for a complete picture of the mismatch problem, it is important to understand how the interests of individual lawyers factor into the selection of pro bono matters. Second, there is a dearth of deeper knowledge of law firm conflicts of interests. Third, there is currently no understanding about how law firm culture impacts the choice of pro bono work for firms and individual lawyers. Fourth, the literature does not discuss how the political climate might impact the choice of pro bono work within firms. And finally, there are no policy suggestions that can help alleviate the problem. Through an empirical exploration of seventy-four in-person interviews across all regions of the United States, this Article makes important contributions to the literature and provides policy recommendations to address the mismatch problem.

To solve the pro bono mismatch, this Article argues for allocating scarce pro bono legal services based on the principle of rationing by aggregation or numbers. Aggregation uses a headcount method to prioritize the highest needs among a range of needs. The highest legal needs should be prioritized while also ensuring representation for other areas of legal services. To that end, I make three proposals: (1) amending the ABA’s Model Rule of Professional Conduct 6.1,[10] which encourages lawyers to provide pro bono work to incorporate language prioritizing legal areas of the highest need; (2) implementing micro-level “pay for preference” regimes; and (3) implementing macro-level “pay for preference” regimes in large law firms to incentivize or nudge law firm lawyers to make pro bono choices while also considering the needs of the poor.

This Article is divided into three Parts. Part I discusses the increasingly important role of large law firms in providing pro bono legal services and provides evidence of the mismatch problem. I rely on survey data and textual analysis of four “Vault Guides to Law Firm Pro Bono Programs” to contrast the needs of the poor with the textual emphasis that law firms place on three areas of pro bono representation. Part II explains how the current literature on the mismatch problem is lacking and why the interview-based qualitative research in this Article is important. I then address the sample and methods used. Part III provides the results of the interview data by laying out four factors that impact the choice of pro bono matters taken on by law firm lawyers. Part III begins with why the mismatch is in fact a “problem” and why it is particularly intractable. Next, I discuss theories around prioritizing legal needs and why I have chosen rationing by aggregation for distributing pro bono legal services. I then propose language for a new Model Rule 6.1 and related comments. Part III also addresses the role of law firms in implementing Model Rule 6.1 but cautions that because the new rule nudges rather than mandates the distribution of pro bono resources, law firms can create a system that prioritizes legal areas of the highest need through micro or macro level “pay for preference” regimes even if Model Rule 6.1 is not amended. These “pay for preference” regimes also serve to nudge lawyers toward the recognition that their interests may not match those of poor clients. Finally, I discuss limitations and drawbacks of having a centralized pro bono system and prioritizing legal areas of the highest need.

Pro Bono Legal Services and the Mismatch Problem

Pro bono legal services provided by the private bar have become an increasingly important avenue for low-income individuals to access civil legal services. This Part discusses the problem of unmet legal needs and the role of law firm pro bono legal services in meeting the legal needs of the poor. It also provides evidence of the mismatch problem by comparing the legal needs of the poor, gathered through survey data, with law firm pro bono choices from textual analysis of Vault data.

Unmet Legal Needs and the Prominence of Law Firms

Access to civil justice continues to be a major problem facing the legal profession, as there are many poor and low-income people without legal representation for critical legal matters such as domestic violence, child custody, eviction, and deportation.[11] Indeed, “[e]ighty percent of the civil legal needs of low-income people are unmet by lawyers.”[12] The Justice Gap Report, written by the Legal Services Corporation (LSC), documents that nationwide, “roughly one-half of the people who seek help from LSC-funded legal aid providers are being denied service because of insufficient program resources. Almost one million cases will be rejected this year for this reason.”[13]

Because of this resource constraint, NLSOs are severely limited in their ability to represent low-income clients—both financially and in terms of the number of available lawyers—and have come to rely on law firms for pro bono and financial resources. Large law firms are highly resourced institutions and have become critical to the provision of legal services to the poor.[14] Over time, pro bono work has become institutionalized within large law firms.[15] Institutionalization is best described by Scott Cummings as the movement of pro bono from being “ad hoc and individualized, dispensed irregularly as professional charity,” to becoming “centralized and streamlined, distributed through an elaborate organizational structure” by private lawyers and “embedded in and cutting across professional associations, law firms, state-sponsored legal services programs, and nonprofit public interest groups.”[16] Within law firms, “[t]he institutionalization of pro bono work refers to the way it has become interwoven into the basic fabric of the profession, where it is governed by explicit rules, identifiable practices, and implicit norms promoting public service.”[17]

To that end, scholars have studied law firm motivations for providing pro bono legal services to many poor individuals who would otherwise have no access to lawyers.[18] Some scholars argue that pro bono provides an opportunity for law firms to improve their reputation among the public[19] and enhance their reputation in recruiting, retaining, and improving the job performance of their lawyers.[20] Others have argued that pro bono provides training, litigation experience, client contact, intellectual challenge, and the opportunity to take responsibility beyond what is otherwise available to junior lawyers in law firms.[21] There are opportunities for marketing and client relations,[22] raising lawyer morale,[23] and—from a professionalism standpoint—providing opportunities for lawyers to give back to society and make a difference in the lives of others.[24]

Scholars have also studied whether law firms value pro bono work. In a survey of firm lawyers, about 52 percent reported that their firms provided no support for pro bono work. Comparatively, only 10 percent indicated that their organizations valued pro bono as much as billable work, while 44 percent believed that pro bono work was viewed negatively.[25] A qualitative study of large law firms in Chicago suggests that firms care about pro bono for self-interested, reputational reasons and do not value it for altruistic reasons.[26] The study further explains that firms are interested in working with NLSOs that support the kinds of pro bono cases that firms choose to support for their own recruitment and training interests.[27]

Another interview-based study suggests that firms carefully conduct pro bono so as not to produce conflicts with corporate clients.[28] The study also suggests that the entire structure of pro bono programs—that is, not including pro bono as billable hours, looking askance at attorneys that work excessive pro bono hours, and providing pro bono through legal clinics where lawyers provide advice rather than retain clients—indicates a lack of commitment to pro bono work.[29]

The literature therefore suggests that large law firm involvement in pro bono work has created avenues for legal services for the needy. However, law firm motivations may be misaligned with the needs of poor clients.

The Mismatch Problem

Despite the fact that the private bar provides pro bono legal services, many low-income individuals still lack legal assistance.[30] The LSC conducts periodic needs assessment surveys of its grantees across the United States to determine the legal needs of the poor.[31] The LSC’s most recent survey from 2017 indicates that “among the low-income Americans receiving help from LSC-funded legal aid organizations, the top three types of civil legal problems relate to family, housing, and income maintenance.”[32] A Chicago Bar Foundation survey conducted in 2005 revealed that the highest legal needs in Illinois “were in the areas of consumer, housing, family and public benefits law.”[33] These four categories made up 66 percent of all legal issues in the survey.[34] While these data are limited,[35] one can surmise that family law and housing are unmet areas of legal need by poor clients. On the other hand, law firms are less likely to prioritize family and housing law. This is the mismatch problem.

To illustrate, I examined the actual text of the “Vault Guide to Law Firm Pro Bono Programs”[36] for the years 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2017,[37] using Atlas.ti, a qualitative data analysis research software. The software provides a powerful tool that can help analyze the text of qualitative data.[38] My goal was to determine how much emphasis law firms placed on three specific areas of law during those years: family, immigration, and housing.[39] The results of the textual analysis are in Table 1, which shows the number of times each term is mentioned in the Vault Guides.

Table 1. Textual Analysis of Vault Guides by Search Term.

| Area of Law | Term | Emphasis |

| Family | ||

| Domestic Violence | 2,245 | |

| Family | 1,372 | |

| Abuse | 374 | |

| Divorce/Matrimonial | 165 | |

| 4,156 | ||

| Immigration | ||

| Immigration | 1,541 | |

| Asylum/Asylee | 1,497 | |

| Refugee | 237 | |

| Deportation/Removal | 194 | |

| 3,469 | ||

| Housing | ||

| Housing | 1,039 | |

| Landlord/Tenant | 897 | |

| Eviction | 119 | |

| 2,055 |

Table 1 shows that, by count, family law is mentioned most frequently across the four Vault Guides. This means that for those four years, law firms emphasized their work in family law the most. Nevertheless, the numbers are misleading because while family law is mentioned 4,156 times in the Vault Guides, domestic violence has the overall highest number of appearances. The reason for this is that law firms tend to do domestic violence work but generally eschew other categories of “family law.”[40] If we omit domestic violence law, the count for family law drops down significantly to 1,902, giving it the lowest emphasis in Table 1. Housing law would be second lowest with a count of 2,055, while immigration law would have the highest emphasis with 3,469 mentions throughout the Vault Guides.

Table 1 contains only a snapshot of law firm pro bono legal services for the years indicated. One cannot fully rely on the data as it measures textual emphasis only. Nevertheless, in conjunction with the LSC survey data, it provides some basis for concluding that firms place a more limited emphasis on housing and family law matters, while the needs of the poor are primarily in housing and family law.

The Mismatch Problem in Pro Bono

This Part addresses the importance of qualitative research in illuminating the pro bono mismatch. It discusses the sample, research methods, and results of the interview research.

What We Don’t Know About the Mismatch Problem

The pro bono mismatch problem—that is, the incongruence between the interest of law firms and their lawyers and the actual legal needs of the poor—is well recognized in the literature. Yet the literature is lacking in important ways. First, we do not have a good understanding of how the interests of individual lawyers factor into the selection of pro bono matters. Second, we do not know how law firm culture impacts the choice of pro bono work for firms and individual lawyers. Third, we lack knowledge about the role of the political climate on pro bono choice in firms. The qualitative research below provides some answers.

Sample and Research Methods

To illustrate how the interests of lawyers, firm culture, and the political climate influence the selection of pro bono matters, this Article employs interview-based empirical research.[41] Specifically, it uses in-depth, qualitative semistructured interviews.[42] In-depth interviews are particularly suited for this research because a study of interests and culture requires the detailed description of decision-making processes and mechanisms in law firms.[43] The data consists of seventy-four in-person interviews across all regions of the United States, broken down as follows: (1) thirty-six interviews of large law firm pro bono professionals[44] and (2) thirty-eight interviews of members of NLSOs.[45] Interviews were in-person, were conducted between March and December 2017, and lasted between one and two hours. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim with participants’ consent. I then manually coded and analyzed the data using Atlas.ti.

I recruited respondents through a snowball sampling method by either contacting them directly or through referrals from other respondents. To be a part of this study, a large firm must have been ranked as an Am Law 100 law firm in the past five years.[46] I selected these elite firms for the study because they are the most influential institutions with regard to pro bono services, as they provide financial and in-kind support to NLSOs.[47]

The law firm pro bono professionals in this study are all lawyers in charge of the full-time management and organization of pro bono legal services within their firms, usually on the global level. These pro bono professionals have the following titles: “Pro Bono Partner,” “Director of Pro Bono,” “Special Counsel of Pro Bono,” or “Pro Bono Counsel.”[48] These pro bono professionals straddle the world of legal services and corporate firms. They serve as “brokers,” bridging the gap between law firms and NLSOs.[49] Most of the pro bono professionals have backgrounds in NLSOs, government legal practice, or law school clinics.[50] Others started out in their law firms as associates and, in some cases, were promoted to litigation or corporate partnerships before becoming pro bono professionals.

I employed maximum variation sampling to reach NLSOs with varying sizes, ranging from very small (two lawyers) to very large (approximately seven hundred lawyers).[51] I also engage various legal practice foci, including general poverty law, of which a majority of the organizations fall, and more specialized practice areas such as immigration, family law, children, housing, arts, benefits, consumer law, and the like. In addition, the location of the nonprofit organizations in this study match the location of the large law firms. Taking this broad sampling approach is useful in interview methods because it allows a researcher to capture the principal outcomes that cut across a great deal of participant or program variation.[52]

Within NLSOs, I interviewed individuals in director positions, and in some cases, I spoke to individuals who coordinate law firm pro bono within their organizations. Pro bono coordinators in NLSOs are mostly found within large organizations that now have lawyer or non-lawyer pro bono coordinators, pro bono directors, or managers as part of the institutionalization of pro bono work across the board. While they are not necessarily the decision-makers within their organizations, these pro bono coordinators tend to have important influence on how their pro bono programs are managed. In some large organizations, I interviewed two individuals, usually the executive director and a pro bono director, manager, or coordinator (depending on the title used within each NLSO). Tables 2 and 3 illustrate the breakdown of the seventy-four interviews and their characteristics.

Table 2. Law Firms (N=36).

| Organization | Interview Type | Region | Interviews | ||||

| Law Firm | Pro Bono Professional | Northeast | 19 | ||||

| Law Firm | Pro Bono Professional | Midwest | 9 | ||||

| Law Firm | Pro Bono Professional | South | 4 | ||||

| Law Firm | Pro Bono Professional | West | 4 | ||||

Table 3. Nonprofit Legal Services (N=38).

| Organization | Region | Interviews | |||

| Nonprofit Legal Services | Northeast | 11 | |||

| Nonprofit Legal Services | Midwest | 11 | |||

| Nonprofit Legal Services | South | 6 | |||

| Nonprofit Legal Services | West | 10 | |||

In addition to interview data, I used findings from my observations at the March 2017 Equal Justice Conference (EJC) when useful. The EJC is an annual gathering of individuals and groups concerned with access to justice, including law firm professionals involved in pro bono work, legal services organization members, corporate counsel, judges, access-to-justice committees within states, and funders and collaborators.[53] The EJC is cosponsored by the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service and the National Legal Aid & Defender Association.[54] The conference brings together these stakeholders to share ideas and discuss issues of pro bono, the public interest, and access to civil justice for the poor.[55]

Pro Bono Choice

The findings below document the factors that influence the choice of pro bono matters selected by individual lawyers and law firms, including the interests of individual lawyers, conflicts, the culture of time, and the political climate.

Lawyer Interests

The concept of “interest” in sociology has been used historically to mean “affinities,” meaning “spheres of activity which persons enter into and occupy in the course of realizing their personality.”[56] “What drives human behavior, in other words, is interest.”[57] Interest determines action.[58] Dominant or more powerful persons can impose or protect their own interests to the detriment of others.[59] Individual or organizational interests either conflict with one another or support one another.[60]

This Article reveals that the interests of individual lawyers drive the legal matters law firms choose. For instance, two pro bono professionals in large law firms explained how they ensure that their lawyers are provided with pro bono matters that interest them:

I want to know what my lawyers want to do. I want to know what cases interest them. I want to know what clients interest them. I want to know what things don’t interest them because I want to serve up to them something that they’ll feel comfortable doing [. . .]. [S]o what we find is that the bulk of what we do tends to be driven by two things: a) What our lawyers want to do in terms of what attracts them, and b) what fits into their schedule.[61]

As the above statement indicates, the pro bono professional’s role is focused on advancing the interests of individual lawyers within the law firm. A second pro bono professional was specific about a particular partner’s interests as driving the pro bono professional’s role:

But there was one lawyer, in particular, who was really bright [. . .] she was supposedly very politically progressive, but never did any pro bono work. And she said [. . .] ‘I really want to do some pro bono work.’ I said ‘great, you’re a great litigation partner, I’m sure we can find [something]. She said ‘no, I want to work on an important class action, but I don’t know anything about like welfare law, or social security, whatever—so, I want to be like the procedural expert on class actions.’ And I was like, ‘I will keep my eye out for that.’ Not surprisingly, [. . .] I’d never heard of anyone asking us for that, but I don’t care.[62]

Pro bono professionals typically meet the interests of lawyers by staying within the comfort zones of individual lawyers and departments in law firms. This is different from the current landscape of the literature on pro bono in large law firms. For example, Leonore Carpenter has made the argument that law firm “[p]ro bono coordinators pick and choose ‘sexy’ cases or ‘easy’ cases over cases that address the most acute needs of the target population.”[63] Deborah Rhode has also argued that law firms tend to send their inexperienced and bored lawyers to do pro bono work for legal services organizations.[64] Carpenter and Rhode therefore place the matter-selection interest in the hands pro bono professionals and their law firms. However, this empirical research suggests that, as volunteers, large law firm pro bono lawyers are usually the drivers of their own pro bono interests.[65] Several pro bono professionals spoke about simply working with associates and partners “to identify [meaningful] opportunities.”[66] One pro bono professional explained that lawyers have the autonomy to choose whether or not to engage in pro bono work at all, even though pro bono professionals, who manage their programs, are tasked with creating successful pro bono programs within their firms: “To some extent[,] we’re held responsible for producing this great pro bono program[,] and we have absolutely no authority over anybody. They can do whatever they want.”[67]

Three pro bono professionals describe what staying within one’s comfort zone means for volunteer lawyers. One explained that lawyers within law firms “want to do something in pro bono that they can feel good about[ ] but also feel competent in. So new areas of law are a little scary [and for many lawyers] it can be challenging to do that kind of work,” especially in practice areas considered to be emotional in nature.[68] Another said that “people feel really connected to doing things in their area of expertise; I’m not asking a hedge fund lawyer to go to court. I’m not asking people to do things that are way out of their comfort zone.”[69] A third pro bono professional explained that “for [the] run-of-the-mill litigation partners, they really are just way too uncomfortable being involved in a family law case.”[70] From these examples, it is clear that the pro bono professional’s goal is to provide matters within these comfort zones.

Nevertheless, while uncommon, some lawyers are interested in going outside their comfort zones for pro bono matters. A pro bono professional explained that some lawyers choose to do matters that are particularly distinct from their everyday practices, but they “want to do something where [they are] not scared that [they are] going to screw up really badly.”[71]

Pro bono professionals therefore seek pro bono work that reflects the interests of lawyers. These interests are usually within their comfort zones. NLSOs understand how lawyer interests impact pro bono matter selection, as the executive director of an organization explained in frustration:

[Lawyers] could be more flexible about where their comfort zone is on behalf of the community, right? So, I think that sometimes they draw—you know—some places and some firms can be pretty narrow [with] what they’re comfortable doing. Like[,] I don’t understand why every big firm in the country can’t help people with simple divorces [. . .]. Why can’t people get over that hurdle, and why can’t we really look really hard at what the need is and not just say[:] [O]h, we want some cute U visa cases, you know, nice and packaged.[72]Conflicts

Empirical evidence confirms the prevailing view that law firms choose pro bono cases to avoid conflicts with corporate clients. When this happens, positional conflict is often a rationale for avoiding certain pro bono matters.[73]

Positional conflicts—sometimes known as business conflicts—may occur when a lawyer or law firm’s presentation of a legal argument on behalf of a client is directly contrary to, or has a detrimental impact on, the position advanced on behalf of a second client in a different case or matter.[74]

Firms avoid matters in areas of law in which many NLSOs seek the help of volunteer lawyers—such as employment law, labor law, and foreclosures—so as not to conflict with their clients’ interests.[75] A pro bono professional explained at length:

All the firms have business conflicts in environmental, foreclosure, employment. These are just areas where big firms cannot do pro bono work because of our client base. There are smaller firms that can. Hopefully, they pick up some of the slack . . . there’s nothing I can do about that [. . .]. [In addition], we might not take that matter because we represent a lot of developers[,] and [. . .] even though there’s no conflict, we don’t want to make a law that’s going to be bad for our clients someday. So even though that day is not today, some day in the future, we don’t want to come up against a case that [this firm] made that hurt developers. So, we wouldn’t take that case. Somebody else who doesn’t represent developers will take that case.[76]

Therefore, positional conflicts also include possible future conflicts with corporate clients. This creates a challenge for NLSOs in their partnerships with law firms. The executive director of an NLSO who had previously been a large law firm commercial partner explained:

They just don’t want to do cases in a certain area because they don’t want to offend banks or employers [. . .]. [T]hose are hard. I mean[,] you understand why the firms do things that way. But it can be frustrating at times. You know there are firms who just don’t do any plaintiffs’ employees work because they represent so many employers and employers don’t want them dabbling around getting the plaintiff’s side of those cases [. . .]. They want this sort of mythical consumer case where the client would be no trouble, the issues would be fascinating[,] and nobody that the firm otherwise represented would be implicated. But that’s hard to come up with.[77]

Therefore, the avoidance of corporate client conflicts is an important goal for law firms in their pro bono partnerships with NLSOs. Some NLSOs are able to assist clients in matters of employment, foreclosure, and other areas involving corporate client conflicts through partnerships with midsized and smaller firms, as well as solo lawyers, all of which do not often have the same conflicts as large law firms. However, many clients simply do not have access to lawyers as a result of these conflicts.

Law Firm Culture of Time

The organizational culture of time in large law firms is another factor that determines which matters get pro bono representation. Organizational culture is a broad concept used in social science research in management, organizations, and sociology.[78] Management scholars define “organizational culture” as a social or normative glue that holds an organization together and expresses values that members of an organization share.[79] Organizational culture is a negotiated order of how things function and how organization members behave, and it is influenced by people with power within organizations.[80] Organizational culture also consists of “systems of abstract, unseen, emotionally charged meaning that organize and maintain beliefs about how to manage physical and social needs.”[81]

Legal scholars have written extensively about organizational culture, including in large law firms.[82] Scholars have also written specifically about the culture of billable hours in law firms.[83] Large law firm lawyers tend to bill clients in rigid time increments.[84] Beyond billing time alone, large law firm lawyers have different cultural constraints depending on their practice areas—transactional or litigation. Unlike firms, NLSOs do not have the same time constraints, as they need not bill their time to clients. In their role as brokers, large law firm pro bono professionals manage time constraints within the parameters of each volunteer lawyer’s practice area. A large law firm pro bono professional provided a useful analogy by comparing litigation to a marathon and transactional work to a sprint. The different approaches to the culture of time in these practice areas have tremendous impact on how lawyers choose pro bono projects. The pro bono professional explained that:

[T]ransactional people run twenty-six one-mile sprints, and there might be a half-a-mile gap in between. Sometimes [. . .] it might just be deal, after deal, after deal. Their lives are very episodic. And so, for them to do what we want them to do [. . .] they need something [so that] when they’re hot, they can set it down, and then when they’re cold, they can pick it up. Litigators just plan for it. So, almost always the first question is: what is the timing of this matter[?] So, we have to fit it in to their schedule, so that drives a tremendous amount of what we do.[85]As a result, pro bono professionals manage their volunteer lawyers’ schedules to accommodate the law firm culture of time. Indeed, one pro bono professional explained how recognition of law firm time constraints is imbued into the definition of what constitutes a “good” nonprofit pro bono client where the organization, rather than an individual, is the client:

That they have a clear objective of what the project is, they are respectful of our attorneys’ time and provide information when asked, and basically, they respect the attorney client relationship. [. . .] [C]lients that are not ideal are ones that tend to ignore whatever the original scope of the relationship was. We signed on to help you negotiate your lease and [. . .] now you are expanding the scope. It is very stressful for our attorneys because [. . .] they committed to take on a certain thing and now it’s exploding.[86]

The above pro bono partner’s observations make clear that the notion of time in large law firms is different from its understanding and use in an NLSO.

This recognition has not gone unnoticed by NLSOs that work with large firm pro bono lawyers. During a panel discussion at the 2017 Equal Justice Conference, the executive director of an NLSO in a conversation with new NLSO pro bono liaisons suggested ways that such organizations can work with judges to minimize the time that large law firm lawyers spend in court when representing pro bono clients:

The judge can allow a pro bono large firm lawyer to go first in court. It’s an appreciation for the lawyers that know they don’t have to sit in court all day that the case can be heard by 8 or 9 a.m. The clerk can also put a pro bono case first. You have a conversation with the judge about having volunteers take on cases that will otherwise be pro se and take too long. Most judges are willing to accommodate that[,] and if you let them understand that other jurisdictions do it[,] then they will feel okay doing it.[87]

The executive director explained that paying attention to the time constraints of large law firm volunteer lawyers is beneficial to indigent clients in court because pro bono lawyers are more likely to take additional matters if time waiting in court is minimized. The executive director further explained the importance of accommodating law firm lawyers’ time constraints because billing time is a law firm experience that does not translate to the NLSO setting.

The impact of the culture of time on law firm pro bono choice is so powerful that associates tend to favor the timeframe of a typical immigration matter, as evidenced by many law firm pro bono professionals and substantiated by NLSOs. For instance, a pro bono professional explained that immigration matters are

really good cases for associates because there’s a huge amount of client contact[,] and because of the backlogs unfortunately in immigration system they can really work them on their own schedule . . . . Whereas if you’re doing a custody case, there’s a judge telling you when your depositions [are] or [what] your discovery schedule [is] and all that kind of stuff, so I think it’s much more manageable.[88]

Another pro bono professional described why asylum law is a recurrent area of choice for law firms:

As an aggregate whole, asylum work has to probably [be the] number one practice area among the top 100 law firms. Two reasons: one, you get some really compelling client. [. . .] Here’s this vulnerable person. They’ve been persecuted in their home country because, they’re a, say, Coptic Christian in Egypt, and the government’s trying to eradicate Christians in Egypt, that’s an easy story to sell. At the same time—then I say: you’re going to meet with the client, you’re going to have six months to file this set of documents. We’re going to give you samples, we’re going to give you training, and you have one deadline and six months to complete it; so when you’re hot, set it down, when you’re cold, would you pick it up? They say: awesome, I’m in. And so, we do that stuff by the truckload. And other firms do, I’ve got to believe, for the same reasons.[89]

NLSOs also explained how the culture of time in law firms has influenced the demand for immigration law matters. For instance, one executive director explained that “a lot of the work that we do is not the kind of work they really want. They prefer . . . discrete work, so they’ll do like asylum petitions, helping people fill out their paperwork.”[90] Another executive director explained that

the pro bono professional say[s] that a lot of [. . .] associates want to do asylum. And the reason is because [. . .] of the timing. You file [. . .] and you don’t have to do anything for another three months. And then, the court date comes, and then you can prep. And then, I think he says, if I remember clearly, it just fits better.[91]

Thus, immigration law is a preferred area because the culture of time is an important factor that has a major impact on the kinds of legal matters that law firms choose.

The Political Climate

Decisions about which pro bono matters to take are also motivated by the political climate of the day. Today, immigration has become a politically charged area of law.[92] While immigration law was generally not considered to be an area of poverty law until recently,[93] it has increasingly become a large focus of the work of many NLSOs and poverty lawyers. NLSOs are keenly aware of the importance of including immigration-related work in their practice to attract private lawyers because of the strong interest and demand for immigration law related work from private firms. To be sure, NLSOs have been practicing immigration law for a long time, as explained by an executive director who said that “most of the top cases legal aid programs for a long time and even today see the most of are some combination of housing, family, and consumer, usually, and immigration’s usually in there pretty high too.”[94]

However, the private bar—particularly large law firms—only recently began to focus its energies on immigration law, especially as a result of recent political developments in the Trump era.[95] Several NLSOs discussed this renewed interest in immigration law in light of how politically charged immigration has become—“immigration right now, everybody wants to do immigration [. . .]. It’s very hot[,] which makes it hard to do other things.”[96] Another explained that “we literally cannot fit in all of the law firms that want to do [immigration] work.”[97] Another NLSO executive director emphasized that

immigration cases probably the last six-to-eight months—because of all the rhetoric and then executive orders that have come out from the federal government about changes in immigration policy. There’s been a great interest in those matters, and so we’ve been able to place those cases very quickly because there is a great deal of interest.[98]

Yet another executive director described the renewed interest in immigration as something the organization had to respond to because if a “pro bono [professional] is knocking on your door and saying, ‘I want to do immigration cases,’ and you have landlord-tenant cases and family law cases, that’s not what [the] associates want to do so you have to be able to respond to that.”[99]

The pressure to take on immigration law matters also comes from law firm board members, as explained by an executive director:

Right now[,] for example, immigration is super, super, super popular because of [. . .] all the Trump stuff, especially trafficking cases. People see that as being very interesting. So, I’ll go to a meeting with our board president, or our communications director, or whatever, and of course, they want to talk up all the interesting immigration work we do and T visa work we do.[100]

As indicated above, policies in the Trump era have spurred a strong interest in immigration law that many NLSOs are under pressure to satisfy, even when other areas of law are left unfulfilled. The last example above shows that nonprofit board members are beginning to join in this push for immigration-related matters. It is important to note though that while the current pro bono interest is in immigration law, this interest may change in the future—particularly with a change in administration. The important point from this research is that while interests and needs can ebb and flow, lawyers should seek to provide legal assistance to those with the highest legal needs at any particular time.

The mismatch problem in pro bono legal services has only been studied in a limited way. By conducting qualitative empirical research of seventy-four interviews involving law firms and NLSOs, this Article aims to provide a deeper understanding about what goes into law firm decision-making regarding pro bono matters. The results indicate that lawyer interests, conflicts, law firm culture of time, and the political climate drive these decisions. Notably, the decisions are hardly ever driven by the actual legal needs of the poor. With this deeper knowledge in hand, the next Part provides policy considerations to address the mismatch problem.

Solving the Mismatch Problem

To address the mismatch problem, I make three proposals. The first is to modify Model Rule 6.1 to include language that addresses the legal needs of the community. The second is to implement a macro-level “pay for preference” regime in law firms. The third is a micro-level “pay for preference” system in law firms. This Article does not argue for a mutually exclusive remedy; one or all of these proposals could be utilized. Indeed, combining all three proposals will likely create the most effective remedy for the mismatch problem.

Why the Mismatch Problem Is Difficult to Solve

There are two important reasons why the mismatch problem is difficult to solve. First, pro bono work is not mandatory and is based entirely on principles of volunteerism, as evidenced by the ABA’s Model Rule of Professional Conduct 6.1 outlined below. Historically, the ABA has sought to amend the Model Rules to mandate pro bono to no avail.[101] Second, pro bono work is an integral part of the legal profession and is unlikely to be replaced with something else. One might wonder, for example, whether pro bono work could be replaced with having large law firms provide funding to NLSOs to represent indigent clients. This is an unlikely outcome largely because NLSOs have become extremely dependent on law firms for money, labor, and prestige by association. And law firms use pro bono work for recruiting, retention, training, professional development, and reputation, as well as for their individual lawyers to give back to society.[102]

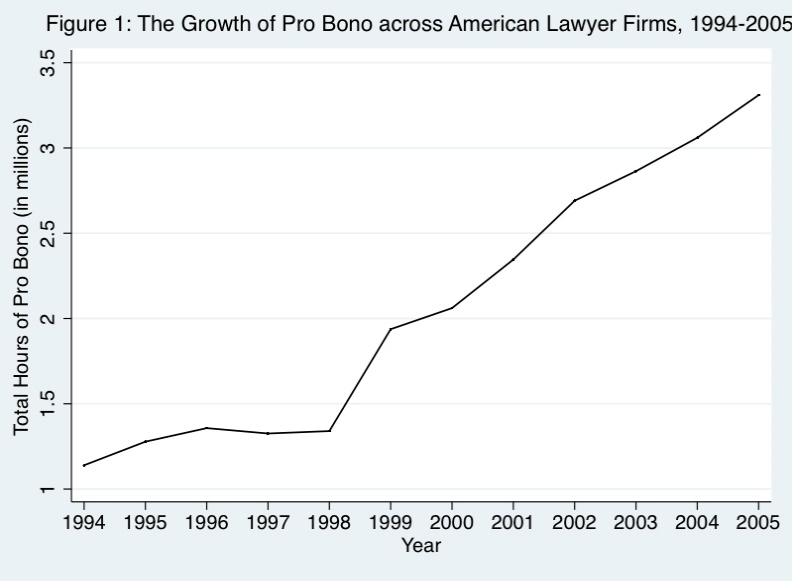

Indeed, since 1998 there has been a steady increase in the number of pro bono hours reported by large law firms as shown in Figure 1 below.[103] Figure 1 illustrates the importance of maintaning pro bono work in firms. And, as discussed above, pro bono work has become institutionalized within law firms.

Figure 1. The Growth of Pro Bono Across American Law Firms, 1994–2005.

Figure 1. The Growth of Pro Bono Across American Law Firms, 1994–2005.

Because of the intractability of the mismatch problem, any solution or proposal must realign firm incentives with those of the poor.

How to Prioritize Legal Needs

Since the demand for legal services is so high and the need is so great while resources are limited, it is important to address how to prioritize legal services. But first, I will discuss the importance of establishing a centralized pro bono system.

The Need for a Centralized System

The structure of pro bono legal services is currently decentralized. Today, most large law firms have lawyer pro bono professionals who serve as brokers, organizing and managing pro bono work for their lawyers.[104] The brokerage of pro bono work often occurs through law firm pro bono professionals who seek legal matters from NLSOs.[105] In addition, individual lawyers sometimes seek legal matters from NLSOs or other avenues, and the resulting clients become their law firms’ clients. The problem with the current system is that it is decentralized. Each firm is connected to each NLSO, rather than a system where all law firms and NLSOs are connected through a centralized system.[106]

Therefore, the first step toward addressing the mismatch problem is to create a centralized pro bono system comprising of NLSOs, large law firms, and bar associations in each state or locality depending on the jurisdiction.[107] A centralized pro bono system would allow participants to have access to information and knowledge about local legal needs. While not complete, we can observe a starting point toward centralized pro bono systems in OneJustice—an organization in San Francisco and Los Angeles—and the Chicago Bar Foundation.[108] OneJustice connects the entire legal services community in California and provides training, information, and resources to NLSOs to assist in their pro bono collaborations.[109] The Chicago Bar Foundation is both a grant-making organization and one that brings together Chicago’s legal community to improve access to justice.[110]

A centralized platform created in each jurisdiction would allow for information sharing so that indigent individuals with the highest legal needs have priority access to legal representation.[111] To have a centralized pro bono system, each state or jurisdiction would create an organization with a web platform.[112] Each NLSO would continue to conduct intakes to determine eligibility for legal services. However, instead of sending matters to law firms through pro bono professionals via email and phone on a monthly basis (as in the current system), the new organization would request new and available pro bono matters from NLSOs in its area. The organization would then rank legal areas of need in the community. Based on that ranking, the organization would determine the area of highest need and send those matters to pro bono professionals in a manner that reflects the proportion of need in the community.

One can imagine a system in which each firm receives a majority of pro bono matters, say 51 percent,[113] in areas of the highest legal need, and pro bono matters in other areas would account for the rest. Pro bono professionals, who continue to serve as brokers between their firms and the nonprofit legal services world, would inform their lawyers about legal areas of the highest need and attempt to place those matters first. For matters that cannot be placed, the new organization can reach out to smaller law firms or solo practitioners to assist in representing indigent clients.

I make this proposal with some caution, especially with regard to the determination of what constitutes the areas of highest legal need in each jurisdiction. At the time of this research, the areas of the highest legal need were family law and housing-related matters across the regions in which interviews were conducted. Legal needs should be reevaluated monthly, quarterly, or within a functional duration in each jurisdiction to ensure that the areas of the highest need receive priority representation.

The proposed centralized platform would ensure that other matters, which are not currently areas of the highest need but are equally important, are not neglected. This clearinghouse can also serve as a source of information for the ABA, individual state bars, and the judiciary.

The Principle of Rationing by Aggregation

Under the current pro bono system, there is no systematic way of choosing pro bono matters. The goal of this subsection is to theorize about how best to determine the distribution of scarce pro bono legal services.

The empirical research discussed in Part II shows that despite the sharp increase in pro bono legal services provided by law firms, the legal areas of the highest need are left unfulfilled. Therefore, this Article relies on the principal of rationing legal services to determine how to prioritize the highest legal needs. The principle of rationing comes from bioethics, where there is a robust literature on the allocation of persistently scarce medical goods, such as organs, ICU beds, and vaccines.[114] The rationing of legal services, like the rationing of medical needs or services, is a difficult endeavor.[115] Rationing, for our purposes, involves determining how to allocate scarce legal resources.[116] After all, how do we decide where to concentrate resources, and for the good of what legal problems?[117] The initial rationing of legal services happens at the doorsteps of NLSOs, when poor clients seek legal services.[118] However, it is important to grapple with how law firms should concentrate pro bono resources. Scholars have discussed several ways in which legal services can be rationed.[119] For instance, rationing can be done using the following methods: (1) first come, first served; (2) lottery, including one of these methods: morally worthy or deserving, emergency, or prioritizing the worse off; and (3) aggregation.[120]

I argue that rationalizing by aggregation is a valuable method for determining how to manage scarce pro bono resources. I have chosen aggregation because the other methods are undesirable. Consider, for example, rationing under a morally worthy or deserving model. Under this model, the goal is to represent individuals who deserve representation. Making a determination about who is deserving or worthy of representation is difficult in practice. Consider an NLSO trying to determine whether to represent a family in an eviction matter when the family had been evicted many times before, or whether to represent an immigrant that had been deported in the past but now needs legal representation. How would the NLSO determine who is morally worthy—the family that is about to become homeless, or the immigrant that can be deported?[121]

Thus, I advocate for the use of aggregation as a viable method to determine the areas of high need. NLSOs often have to decide whether to provide some benefit to many individuals or concentrate that benefit in a small number of people.[122] I argue that rationing by aggregation should guide how pro bono legal services are distributed when law firms and NLSOs collaborate to provide free legal services to the poor. Specifically, NLSOs should decide where to concentrate legal services by considering the aggregate of individuals with needs in particular areas of law.

A criticism of the model of rationing by aggregation is that it treats clients in an aggregative manner rather than individually, which amounts to denying clients equal concern because it distinguishes between them on the basis of the groups to which they belong.[123] “A client’s problem is addressed only if enough other clients share that same problem.”[124] For instance, if a particular locality happens to have many individuals over the age of sixty-five, an NLSO can observe a need for legal services for the elderly and either establish an organization focused on elder law or concentrate resources on that area of law. In this example, the organization prioritizes the legal needs of the elderly by the number of elderly persons who seek legal assistance over and above other legal needs.

While it is not a perfect solution, rationing by aggregation is a worthwhile way to distribute pro bono legal services for a number of reasons.

First, because pro bono work involves the transfer of poor clients from NLSOs to law firm lawyers, any form of rationing pro bono must be conducted in a systematic manner. To illustrate this, consider the application of a first come, first served or lottery system to pro bono work. It would be extremely challenging for law firms and NLSOs to determine what clients came first in the chain of needy clients to accurately apply the model. This is because a determination of the order of clients can be done through NLSO intake processes, communication between NLSOs, and law firms—including through pro bono professionals and individual lawyers.

Second, aggregation, at least in terms of how this Article proposes to utilize it, is infused with a level of fairness that the other forms of rationing lack. Consider the principle of deservingness, or priority to the worst-off. It would be challenging to determine the deservingness of individual clients. For instance, making the determination of whether a child who is embroiled in a custody battle is more deserving than a family with three young children who are about to be evicted or a woman experiencing domestic violence would be nearly impossible.

While aggregation treats individuals as part of a group with similar legal problems, it does not have to be all-or-nothing. We can ensure that other areas of legal need are also represented. As I propose in the next section, the legal area of the highest need can be determined as a percentage of other legal needs. While the highest need would be prioritized, other legal needs would also be addressed, but on a smaller scale.

In addition, it is important to describe how to determine the “greatest legal need.” There is certainly no perfect measure to determine what the greatest need in a community is. As a result, this Article relies on nonprofit intake processes for that determination. NLSOs conduct intakes to determine, among other things, whether a client (1) has a legal problem, (2) whether the client is eligible for legal services, and (3) whether the legal problem can be addressed by that NLSO. NLSOs are best situated to determine legal need because they are often the avenue through which the indigent access legal services. The greatest legal need is therefore the need with the highest number of intakes per legal issue accepted across all organizations in a particular jurisdiction or community.[125]

Modifying Model Rule 6.1

The goal of modifying Model Rule 6.1 is to send a strong signal about prioritizing the legal needs of the poor.

Current Text of Model Rule 6.1: Voluntary Pro Bono Publico Service

Every lawyer has a professional responsibility to provide legal services to those unable to pay. A lawyer should aspire to render at least (50) hours of pro bono publico legal services per year. In fulfilling this responsibility, the lawyer should:

(a) provide a substantial majority of the (50) hours of legal services without fee or expectation of fee to: (1) persons of limited means or, (2) charitable, religious, civic, community, governmental and educational organizations in matters that are designed primarily to address the needs of persons of limited means; and

(b) provide any additional services through:

(1) delivery of legal services at no fee or substantially reduced fee to individuals, groups or organizations seeking to secure or protect civil rights, civil liberties or public rights, or charitable, religious, civic, community, governmental and educational organizations in matters in furtherance of their organizational purposes, where the payment of standard legal fees would significantly deplete the organization’s economic resources or would be otherwise inappropriate;

(2) delivery of legal services at a substantially reduced fee to persons of limited means; or

(3) participation in activities for improving the law, the legal system or the legal profession. In addition, a lawyer should voluntarily contribute financial support to organizations that provide legal services to persons of limited means.[126]

Proposed Model Rule 6.1

The proposed Model Rule 6.1 incorporates the principle of rationing by aggregation to target the highest legal needs in the community at any given point in time. Below, I use italicized, boldfaced text to show how changes can be made to section (a) of the Rule.[127]

Rule 6.1: Voluntary Pro Bono Publico Service

Every lawyer has a professional responsibility to provide legal services to those unable to pay. A lawyer should aspire to render at least (50) hours of pro bono publico legal services per year. In fulfilling this responsibility, the lawyer should:

(a) provide a substantial majority of the (50) hours of legal services without fee or expectation of fee to:

(1) persons of limited means who have been determined to be part of a group possessing the highest legal need in the community or,

(2) charitable, religious, civic, community, governmental and educational organizations in matters that are designed primarily to address the needs of persons of limited means who have been determined to be part of a group possessing the highest legal needs in the community . . . .

Proposed Comment on Model Rule 6.1

[13] The addition to paragraph (a) adds language to the Rule prioritizing the representation of individuals with the highest legal needs in the community, as determined by each jurisdiction and depending upon local needs and local conditions. In case of conflict, especially experienced by law firm lawyers, if reasonable accommodation cannot be made with the client who is the source of the conflict, then legal needs determined to be next in priority should be considered. This paragraph was added to aid lawyers in the selection of targeted pro bono representation; it is nonbinding.

The current ABA Model Rule 6.1 has been adopted in whole or part by a majority of the states and the District of Columbia.[128] Nevertheless, some states depart significantly from the structure and substance of Model Rule 6.1. Notably, California locates its pro bono rule in Comment 5 of Rule 1.0, which defines the purpose and function of the Rules of Professional Conduct.[129] Texas’s pro bono rule is listed as Preamble 6 of its Code, and looks like an amalgamation of the 1969 and 1983 versions of Model Rule 6.1.[130] All in all, there is hardly any uniformity in Model Rule 6.1 among the states.[131]

However, given the importance of the proposed amendments to addressing the incongruence between lawyers’ interests and the legal needs of the poor and because the goal of the amendment is to address local legal needs, states should amend their ethical codes to incorporate the new Rule as necessary for their jurisdictions’ access-to-justice efforts.[132] Uniformity across the states in noting the importance of focusing pro bono work on need would provide additional leverage for these proposals.

The Role of Law Firms

Model Rule 6.1 is not mandatory; there is no disciplinary consequence attached to implementing the proposed new Rule 6.1. Therefore, it is important to recognize that some lawyers will choose to ignore it. Since large law firms have become critical to the provision of legal aid, it is important to provide incentives for lawyers in law firms to comply with the proposed Rule 6.1.[133] For this reason, I provide two proposals that can be followed by law firms seeking to encourage their lawyers to engage in pro bono work targeting the highest legal needs in their communities.[134] Even if the new Model Rule 6.1 is not adopted, law firms can create and implement these proposals for the benefit of the poor in their jurisdictions.

Pay-for-Preference: Macro Level

For starters, a proposal that seeks to suggest or impose a financing requirement on a private organization is bound to be met with skepticism. Therefore, I start this section by noting that the current Rule 6.1 states that “a lawyer should voluntarily contribute financial support to organizations that provide legal services to persons of limited means.”[135] I consider “pay-for-preference” a way to meet this financial requirement under Rule 6.1.[136] Pay-for-preference is advantageous to both law firms and NLSOs. It is important to distinguish pay-for-preference from “pay-to-play,” a phenomenon that requires law firms to pay NLSOs a certain amount of money as incentive to engage in pro bono legal services with their organizations.[137]

Pay-for-preference would allow law firm lawyers to choose the volunteer projects they would like to engage in while providing for the needs of the community. Under the centralized pro bono system, if a law firm lawyer’s preferred legal areas do not match the areas of the highest need within the community, the lawyer’s firm would sponsor another area of law within the organization. For example, if lawyer or law firm X wants to take on immigration law cases, but the area of the highest need is housing law, law firm X would sponsor an organization—let’s call it Y—which focuses on housing law, by funding a part of its program, or providing what is akin to a fellowship program where one or more of its lawyers goes into the organization for a number of months to represent clients directly.[138] Then organization Y would provide law firm X with its desired immigration law matters, if available.

Another use for pay-for-preference would be if the legal areas of the highest need become deeply incompatible with law firm interests. For example, we can imagine a world where employment-based claims become the legal area of the highest need in a particular jurisdiction, or even nationally. Large law firms have historically rejected the representation of poor clients in employment law on the basis that they create positional conflicts;[139] thus, pay-for-preference can serve as an avenue to sponsor NLSOs who represent clients in employment law, or other areas of law, to seek other representation, while firms can represent poor clients with other legitimate legal matters. With pay-for-preference, Model Rule 6.1 will likely be more successfully adhered to, and firms who are interested in other legal areas can receive their preferences in pro bono matters.

A limitation of a macro-level pay-for-preference regime as I have proposed here is that, if many law firm lawyers choose to “pay for preference,” the new Rule 6.1 may not function to give priority to areas of the highest legal need. In other words, if most lawyers choose to opt out of Rule 6.1 by paying for preference, then the Rule becomes weak. If Rule 6.1 is not adopted and firms incorporate macro pay-for-preference regimes, the same limitation applies, as legal areas of the highest need could be ignored. To combat this problem, the proposed clearinghouse could limit the number of “pay for preference” requests honored per firm on a yearly basis. The clearinghouse could also impose a policy to exponentially increase the amount of money a firm would have to pay to opt out. This would likely deter law firms from opting out except under limited conflict exceptions.

Pay-for-Preference: Micro Level

A micro-level pay-for-preference system would be organized and implemented internally on the firm level, unlike the macro pay-for-preference described above, which applies to law firms broadly. Each firm can incentivize its lawyers to take matters where the need is greatest in the community by giving more credit to pro bono hours in areas of high legal need. To implement micro-level pay-for-preference, firms can require lawyers to choose pro bono matters beyond a certain number of hours—say one hundred in any given year—in legal areas of high need. Alternatively, firms can allow lawyers to bill pro bono hours in areas of the highest need as time and a half. For instance, an associate can bill 1.5 hours for every hour spent representing a client in a family law matter under this system.

The first limitation of a micro-level pay-for-preference system is incentivizing firms to organize or implement pro bono restrictions on their lawyers. An imperfect solution to this problem is for pro bono professionals to advocate for jurisdictional legal needs within their firms. This solution is imperfect because lawyers can still choose to do whatever they want, although some influential pro bono professionals who wield a lot of power can sway lawyers’ decision-making.[140]

Limitations and Drawbacks

This subsection addresses limitations and drawbacks of establishing a centralized pro bono system and prioritizing legal areas of the highest need through aggregation. I take up these issues systematically below.

Limitations of a Centralized Pro Bono System

There are several limitations of having a centralized pro bono system. First, a jurisdictional-level organization or clearinghouse may be difficult to implement in certain areas. While few would disagree about the need for more family law representation at present, many organizations may have disagreements about what constitutes legal areas of the highest need. While this is a real challenge, it is likely to be a rare occurrence because NLSOs would inform the clearinghouse about their needs. A related limitation is that a centralized pro bono system may be challenged in certain jurisdictions where there is competition for pro bono matters because firms and organizations may not necessarily want to share pro bono opportunities generally. It is true that a centralized pro bono system may effectively eliminate the opportunity to compete for pro bono matters. However, being able to meet community legal needs likely trumps the need to compete with other law firms or NLSOs for pro bono matters.

Second, having a centralized system will likely mean creating new organizations to manage the pro bono system in each jurisdiction. This clearinghouse would need resources that are already challenging to come by. Some may argue that instead of creating new organizations, states should fund the hiring of more legal services attorneys to help meet the needs of clients that the private bar does not. These are important limitations. However, a centralized pro bono system does more than allow for the implementation of a proposed Rule 6.1. A centralized system would allow for information symmetry, so that law firms and NLSOs have access to and information about pro bono opportunities and resources in their communities. In addition, funding NLSOs is important regardless of whether a centralized pro bono system is implemented because pro bono work cannot substitute the work of NLSOs, who are experts in poverty law. Moreover, the legal profession values pro bono legal services and has codified it in the Model Rules. Indeed, even if NLSOs receive additional funding to represent clients that are currently without representation, law firms and lawyers will continue to represent pro bono clients. Thus, it is important to remedy problems within the pro bono system. Pro bono is here to stay and provides valuable legal services for many poor clients.

Relatedly, there is a risk that a clearinghouse or new organization may be treated like an outsider, with no power or influence to ensure that it receives and processes information as it should. And the clearinghouse may not have enough resources to further its work. Thus, there is a recognition that without high level support, a clearinghouse model may not be the most effective approach.[141] The best way to combat this problem is to ensure that both law firms and NLSOs are supportive of the establishment of a clearinghouse because without their support, the organization will lack either information or funding. To incentivize the participation of law firms, the clearinghouse can solicit the support of corporate clients, who have a large influence on law firm decision-making.[142]

Finally, some jurisdictions may require more fine-grained analysis and establishment of community needs. This is particularly salient for rural communities. Jurisdictions may need to determine need by locality rather than on a state-wide basis so as not to advantage some parts of the state over the other. Therefore, it is important for the proposals to be adapted to suit each state’s constitution and legal needs.

Limitations of Prioritizing Legal Areas of the Highest Need

The overall proposal[143] in this Article argues for prioritizing legal matters of the highest need in the community. While rationing by aggregation is theoretically and practically useful in addressing the mismatch problem, it has some drawbacks.

First, the question remains whether large law firm lawyers would be willing to prioritize legal areas of the highest need. Rationing by aggregation and making suggestions about how to allocate pro bono legal services will likely be challenged. This is because the proposals in this Article may appear to infringe upon the autonomy of law firm lawyers to choose their pro bono matters. After all, people mostly choose to represent individual clients or organizations for free based on their personal interests. I note the issue of autonomy as a limitation. Particularly, it may seem like instead of representing individuals with the highest legal needs, some lawyers may shun receiving a mandate and choose not to engage in pro bono work at all. Deterring people from taking on pro bono work is not the outcome that any access-to-justice advocate would want. Thus, I note here that pro bono work is not mandatory,[144] and the proposals made here are not mandates; lawyers can and will still choose not to follow them. Rather, they can be understood as “nudges,” as described by Cass Sunstein. “Nudges preserve freedom of choice and thus allow people to go their own way.”[145]

Even if we take rationing by aggregation as a nudge, the proposals made here are valuable in that they raise consciousness about community legal needs and provide information to lawyers who may not know that the highest legal needs in the community differ from their interests.

Second, rationing by aggregation could impede the creation of expertise in established legal services areas of law. NLSOs prefer that law firms develop areas of expertise in particular legal areas so that firms can take on more matters in their areas of expertise with little to no supervision. As a legal services director remarked during one of the interviews conducted for this research, “We are bringing the subject matter expertise. We are holding their hand, but it’s less work for us if they’ve already done a case like that before, and then they could do it again.”[146]

Essentially, NLSO lawyers mentor large firm lawyers through their representation of poor clients until they have acquired experience representing clients with similar legal problems.[147] For NLSOs, the goal is for firms to become self-sufficient client legal representatives because mentoring law firm lawyers through legal matters is expensive in terms of time and labor.[148] By suggesting that legal areas of the highest need be reevaluated often, it is possible that these areas of need would change frequently, reducing the possibility of the development of expertise around certain legal issues. The hope is that, over time, firm lawyers can develop expertise in a myriad of legal issues, making this concern mostly irrelevant.

Third, there is potential for gaming the system to obtain priority pro bono representation for one’s NLSO. Consider a time when the legal area of the highest need is human rights law. To obtain pro bono priority, NLSOs, through their intake processes, can choose large numbers of clients with human-rights-related matters and turn down clients with other legal problems. While this may seem like an unfair outcome, NLSOs already engage in rationing at their door steps by deciding who to represent.[149] Indeed, creating an NLSO with a focus on particular legal issues of law or policy is a form of rationing.[150] An NLSO that goes by the name of “The Education Law Center,” for example, would necessarily turn away clients who do not fit the legal problems that it was established to address.[151]

Prioritizing individuals with the highest legal needs is justifiable regardless of these potential concerns because it not only ensures that the legal profession meets the needs of the community, but also helps to conserve scarce resources for NLSOs.

Conclusion

The unmet legal needs of the poor remain very high. Law firms have taken an increasingly important role in providing legal services to the poor by partnering with nonprofit legal services organizations (NLSOs) to provide pro bono legal services. While law firm involvement has important benefits, such as increasing the capacity to reach a large number of people and providing avenues for money, labor, and prestige resources for NLSOs, it has also created some problems—including the incongruence between the interests of law firms and their lawyers and the actual legal needs of the poor, or the pro bono mismatch. This Article makes important proposals to address the pro bono mismatch problem, including creating a centralized pro bono system to address the asymmetry in information among law firms and NLSOs, modifying the ABA’s Model Rule of Professional Conduct 6.1 that provides aspirational pro bono goals for lawyers to encourage lawyers to choose pro bono work based on community need, and incentivizing law firm lawyers to focus their pro bono practices on the actual legal needs of the poor. These proposals would encourage law firm lawyers to prioritize the needs of the poor in pro bono legal services.

- Earl B. Dickerson Fellow and Lecturer in Law, University of Chicago Law School; J.D., Columbia Law School; Ph.D., M.A. (Sociology), Northwestern University. I am indebted to Genevieve Lakier for providing feedback at multiple stages of this project. For invaluable comments and suggestions, I am grateful to Emily Buss, John Rappaport, Adam Chilton, Bertrall Ross, Monica Bell, H. Timothy Lovelace, Guy-Uriel Charles, Jennifer Nou, Fred Smith, and Shaun Ossei-Owusu. Thanks also to Geoffrey Stone, Aziz Huq, Douglas Baird, Emma Kaufman, and Cree Jones for helpful discussions. This research was supported by The Alumnae of Northwestern University Grant. ↑

- . Scott L. Cummings & Deborah L. Rhode, Managing Pro Bono: Doing Well by Doing Better, 78 Fordham L. Rev. 2357, 2391 (2010). There are variations of this statement in the literature. See, e.g., id. at 2427 (explaining that pro bono work is designed first to maximize training opportunities for associates); Scott L. Cummings, The Politics of Pro Bono, 52 UCLA L. Rev. 1, 129–30 (2004) (showing that certain legal matters are privileged while others are marginalized); Stuart Scheingold & Anne Bloom, Transgressive Cause Lawyering: Practice Sites and the Politicization of the Professional, 5 Int’l J. Legal Prof. 209, 222 (1998) (explaining the pro bono mismatch in the context of corporate client conflicts). ↑

- . Rebecca Sandefur, Lawyers’ Pro Bono Service and Market-Reliant Legal Aid, in Private Lawyers in the Public Interest: The Evolving Role of Pro Bono in the Legal Profession 95, 103 (Robert Granfield & Lynn M. Mather eds., 2009); see also Stephen Daniels & Joanna Martin, Legal Services for the Poor: Access, Self-Interest, and Pro Bono in Access to Justice 162 (Rebecca L. Sandefur ed., 2009); John M.A. DiPippa, Peter Singer, Drowning Children, and Pro Bono, 119 W. Va. L. Rev. 113, 129–30 (2016); Esther F. Lardent, Positional Conflicts in the Pro Bono Context: Ethical Considerations and Market Forces, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 2279, 2279 (1999); see generally Deborah L. Rhode, Rethinking the Public in Lawyers’ Public Service: Strategic Philanthropy and the Bottom Line, in Private Lawyers in the Public Interest, supra at 251; Robert Granfield & Lynn M. Mather, Pro Bono, the Public Good, and the Legal Profession, in Private Lawyers and the Public Interest, supra at 1, 11; Esther F. Lardent, Positional Conflicts in the Pro Bono Context: Ethical Considerations and Market Forces, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 2279, 2279 (1999). ↑

- . The author refers to institutions commonly known as “public interest organizations” as “nonprofit legal services organizations” (NLSOs) throughout this article. NLSO captures the form and substance of these organizations. NLSOs are “the primary institutionalized structure for serving the civil legal needs of those who cannot otherwise afford a lawyer . . . . [and] are virtually the only institutionalized means for supporting dedicated, experienced lawyers with expertise in the particular legal areas most relevant to representing poor, disadvantaged, or underserved constituencies.” Laura Beth Nielsen & Catherine R. Albiston, The Organization of Public Interest Practice: 1975–2004, 84 N.C. L. Rev. 1591, 1596 (2006); see also Cummings & Rhode, supra note 1, at 2381. ↑

- . Cummings & Rhode, supra note 1, at 2381. ↑

- . Id. at 2393–94, 2429. ↑

- . Daniels & Martin, supra note 2, at 160. ↑

- . Cummings, supra note 1, at 123. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct r. 6.1 (Am. Bar Ass’n 2019). ↑

- . See generally Cummings & Rhode, supra note 1; DiPippa, supra note 2; Bryant Garth, Comment: A Revival of Access-to-Justice Research, 13 Soc. Crime L. & Deviance 255 (2009); Victoria J. Haneman, Bridging the Justice Gap with a (Purposeful) Restructuring of Small Claims Courts, 39 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 457 (2017); Ann Juergens & Diane Galatowitsch, A Call to Cultivate the Public Interest: Beyond Pro Bono, 51 Wash. U. J. L. & Pol’y 95, 96 (2016); Latonia Haney Keith, Poverty, the Great Unequalizer: Improving the Delivery System for Civil Legal Aid, 66 Cath. U. L. Rev. 55 (2016); Margaret Colgate Love, The Revised ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct: Summary of the Work of Ethics 2000, 15 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 441, 474 (2002). ↑

- . Jules Lobel & Matthew Chapman, Bridging the Gap Between Unmet Legal Needs and an Oversupply of Lawyers: Creating Neighborhood Law Offices—The Philadelphia Experiment, 22 Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L. 71, 73 (2015). ↑

- . Legal Services Corporation, Documenting the Justice Gap in America: A Report of the Legal Services Corporation 12 (2009). “Because this figure does not include people seeking help from non-LSC-funded programs, people who cannot be served fully, and people who for whatever reason are not seeking help from any legal aid program, it represents only a fraction of the level of unmet need.” Id. ↑

- . Daniels & Martin, supra note 2, at 149. ↑