On the one hundredth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, this Article reflects on the legacy of Black women voters. The Article hypothesizes that even though suffrage was hard fought, it has not been a vehicle for Black women to meaningfully advance their political concerns. Instead, an inverse relationship exists between Black women’s political participation and their relative level of socioeconomic and political well-being. Taking recent national elections as a case study, the Article identifies two sources of Black women’s political powerlessness: “caretaker voting” and the “trapped constituency problem.” The Article concludes that Black women’s strong voter turnout coupled with their reliable support of the Democratic Party has had the perverse outcome of cementing their irrelevance in the electoral system. To disrupt this trend, the Article proposes a new path forward.

PDF: Ezie,* Not Your Mule?

Introduction

2020 marked the one hundredth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which granted women the right to vote.[1] Ratified on August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment was the product of a decades-long battle waged by women’s suffragists across various ethnic backgrounds and was initially celebrated as a triumph for all women.[2] One day after ratification, the New York Times declared that the Nineteenth Amendment brought an end to “the long struggle for woman suffrage in this country.”[3] Part of the excitement that attended ratification of the Amendment was the belief that voting would provide women a valuable mechanism to advance their political concerns.[4] Yet in the case of Black women, both of these assumptions have proven false.

As white women confidently marched to the polls in the wake of the Nineteenth Amendment, the right to vote remained largely theoretical for Black women voters for half a century longer. As Black women struggled to obtain meaningful access to the franchise, their natural allies in the feminist movement and the Republican Party remained conspicuously absent.[5] While Black women’s political participation today rivals that of all other demographic groups, voting has still not become a vehicle for Black women to meaningfully advance their political concerns. Instead, as this Article contends, Black women’s strong participation in national elections, coupled with their reliable support of the Democratic Party, has had the perverse outcome of making them a “trapped constituency”: a group whose votes are relied upon by the political establishment but whose political preferences are largely irrelevant.[6]

The problem facing Black women voters is not abstract. Rather, as Black women’s political participation grows, their political power is shrinking, as is their share of American prosperity by all available metrics.[7] Even before the global coronavirus pandemic unleashed an unprecedented recession, Black women were clinging to the bottom of the U.S. social strata in terms of income, life expectancies, and health outcomes.[8] Black women are also disproportionately impacted by criminalization and mass incarceration and locked out of educational opportunities.[9] Adding insult to injury, the Democratic Party rarely prioritizes Black women despite their dependable support; instead, the Party devotes its time and attention to appeasing white, moderate, suburban voters who have come to represent a coveted swing vote.[10] The ways that Black women voters are taken for granted and sidelined by the Democratic Party ultimately beg the question: Why should Black women vote at all?

Although most commentators are reluctant to question the utility of voting—particularly in an election year where Black women voters were essential in removing Donald Trump—this Article contends that many of the common justifications for voting in national elections are mere myths where Black women are concerned. Primary among these myths are the ideas that voting enhances Black women’s experiences of lived equality, that voting ensures that the Supreme Court acts as a guardian of civil and constitutional rights, and that voting guarantees that issues of racial justice are prioritized within the Democratic Party.[11]

By examining the relationship between Black women’s voting and political outcomes, this Article concludes that Black women are “trapped constituents” within the Democratic Party—a group whose votes are taken for granted because their political alternatives are limited.[12] The Article asserts that unless Black women voters are content to continue playing a caretaker role for American Democracy, important shifts are necessary. Specifically, this Article proposes that Black women pursue strategies—including strategic non-voting—that put them on par with swing voters, allow them to reclaim political power, and assert “I am not your mule” once and for all.

I. The Nineteenth Amendment and Black Women’s Century-Long Struggle to Secure the Vote After Emancipation

To understand the electoral force that Black women have become, it is helpful to start with the fifty-year fight that activists waged to secure Black women meaningful access to voting following the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

A. Black Women’s Ephemeral Right to Vote

In the months following ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, thousands of Black women across the United States flocked to the polls in states such as Georgia and Alabama, aided by Colored Women’s Voter Leagues that formed to support aspiring first-time voters.[13] However, Black women’s voting rights remained largely ephemeral for another 50 years due to the color line that shaped American life following emancipation.

In many jurisdictions, Black women attempting to vote were systematically rebuffed using voter suppression tactics that expanded and perfected disenfranchisement tactics first deployed against Black men following the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. One oft-used measure was the poll tax, which conditioned voting on an individual’s ability to pay a fee ahead of primaries—fees which accumulated if they went unpaid.[14] Literacy tests were another tactic used in both the North and the South to effectively penalize Black voters for the long period—during enslavement and thereafter—where they were denied access to quality education.[15] Literacy tests were also notable for their arbitrariness—endlessly shapeshifting as Black voters became more educated.[16]

When voter suppression measures were challenged, the U.S. Supreme Court gave their architects broad sanction. For instance, in United States v. Reese, the Supreme Court failed to intervene when Kentucky refused to let a Black man register to vote on account of a poll tax.[17] In a tortured opinion, the Court held that the Fifteenth Amendment did not guarantee a universal right to vote and that voting restrictions were a matter of states’ rights so long as they were evenly applied.[18] Likewise, in Williams v. Mississippi, a unanimous Supreme Court upheld Mississippi’s complex web of poll tax laws, notwithstanding candid admissions from state officials that their aim was to disenfranchise Black male voters.[19] Then, in Giles v. Harris and Giles v. Teasly, the Supreme Court rejected legal challenges to literacy tests brought on behalf of thousands of disenfranchised Black male voters in Alabama.[20] The Supreme Court’s early and repeated endorsement of voter suppression tactics allowed these measures to become ubiquitous in Southern states—ensuring that Black men’s voting rights remained largely symbolic for a century.[21] It also paved the way for the disenfranchisement Black women voters encountered after the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage.[22]

When determined Black voters persisted in their efforts to vote and sought to overcome their legal barriers—saving up funds to satisfy poll taxes and studying for literary tests—new voter suppression measures unfurled in the South.[23] Chief among them were all-white primaries, which excluded Black voters from participation.[24] As one historian explained:

Ingeniously, the primary was, or could be considered, a private [political party] affair, rather than a public [governmental] function and as such immune to the strictures of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Thus blacks could be excluded from participation in Democratic Party primary elections and in the one party South it meant complete disfranchisement since winning the primary was tantamount to election.[25]

All-white primaries were not completely dismantled until the 1950s, with Texas refusing to eradicate them until 1953.[26] Prominent Black political scientist Ralph Bunche dubbed white primaries “the most effective device for the exclusion of Negroes from the polls in the South.”[27]

Black women seeking to exercise their constitutional right to vote also became targets of racialized violence as the Nineteenth Amendment sparked a revival of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan unleashed a new wave of racial terrorism aimed at denying Black people entry into civic and political life.[28] Racial violence, coupled with the expansion of state-sanctioned voter suppression efforts, proved highly effective at depressing voter registration and turnout among Black women as time went on—particularly in the South where a majority of Black voters continued to reside.[29] Accordingly, while some Black women triumphantly succeeded in their quest to vote, far more did not, and the right to vote conferred by the Nineteenth Amendment was rendered all but ephemeral for Black women for decades to come.

B. Feminist Apathy, Republican Indifference, and the Black Organizing Revival

The disenfranchisement of Black women voters was met with apathy by white suffragists and Republicans, confirming the enduring significance of race in American life.[30] In addition to harboring notoriously bigoted views, prominent white suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton made a political calculation to sideline Black women within the voting rights movement to clear a path for ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in the South.[31] White suffragists also maintained racial segregation in movement-organizing spaces, while others quite literally insisted that Black suffragists move to the back of parades and public assemblies.[32] The fleeting moments of cross-racial organizing that preceded the Nineteenth Amendment evaporated after its passage. As historian Liette Gidlow explains:

At the midpoint, in the 1920s, white women broadly failed to stand up for Black women’s voting rights or for those of Black men. And at the center of it all stood African American women who struggled across generations to secure voting rights for their community and for themselves and who sometimes reached out, with little success, to white women’s groups to join them in that fight.[33]

Indeed, once empowered with the franchise, many white women saw voting as “an opportunity to solidify the political power of whites and native-born citizens.”[34] White suffragists began vocalizing support for poll taxes that served to depress Black women’s votes.[35] Others dismissed the widespread disenfranchisement of Black women voters as a “‘race issue[]’ unrelated to [the] women’s rights agenda.”[36] Another subgroup of white women began to enthusiastically join the Ku Klux Klan, forming women’s-only chapters for the express purpose of promoting “pure womanhood” and opposing racial equality.[37] The fractures in the suffrage movement presaged the racial fissures that emerged within feminism and may explain why, to this day, there is no cohesive cross-racial “women’s vote.”[38]

The Republican Party also proved indifferent to the obstacles faced by Black women seeking to vote. By the 1920s, the Republican Party had placed considerable distance between itself and the Party of Lincoln that helped to engineer Emancipation.[39] Aside from a few radical members of the party, many Republicans stood idle as Black Codes—laws that criminalized Black people for innocent conduct—swept across the American South.[40] Republicans increasingly remained silent as the Ku Klux Klan laid siege on Black Americans trying to participate in civil life.[41] Republican-nominated judges and elected officials also failed to meaningfully intervene when Black men, newly empowered with the right to vote in 1870, were systematically disenfranchised by other means.[42]

Likewise, Republican Party officials in the South looked on with bored indifference while Black women struggled to make their right to vote more than mere words on paper.[43] As Gidlow writes, “[t]he feeble southern Republican Party might have welcomed an influx of new supporters as an opportunity for growth, but it did not.”[44] Instead, “southern Republicans rebuffed Black supporters in order to reassure newly enfranchised white women that . . . they ‘were not joining a “Negro” party.’”[45] Thus, the struggle for voting rights precipitated by the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments cemented the Republican Party’s rebrand from the Party of Emancipation to a Party squarely focused on white identity.[46]

Although Black women were largely shut out of the political process and abandoned by the broader feminist movement and Republican Party, their resolve to vote did not diminish. In the half-century following the Nineteenth Amendment, aspiring Black voters in the South tirelessly organized and fought to build power. For instance, Fannie Lou Hamer became a crusader for voting rights in Mississippi who persisted with her activism, despite being arrested and brutally beaten.[47] Similarly, Amelia Boynton Robinson, a life-long activist and contemporary of Martin Luther King Jr. who fought tirelessly for voting rights, was viciously beaten while protesting for voting rights on Bloody Sunday—an event that became a turning point for the voting rights movement.[48]

The activism and sacrifice of women like Boynton and Hamer helped usher in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed the poll tax and other voter suppression measures, created a system for electoral oversight, and in turn, finally conferred Black women voters meaningful access to the franchise nationwide.[49]

II. Black Women Voters: The Current Picture

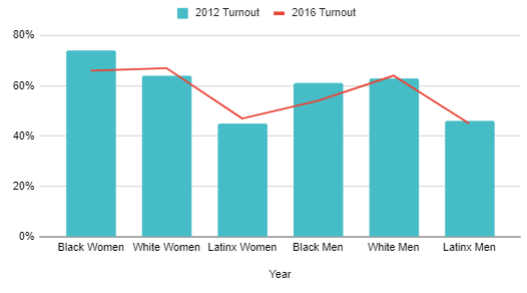

Graph I: Voter Turnout by Race and Gender: 2012 & 2016[50]

A. Black Women Are America’s Most Consistent Voters

For more than a decade, Black women’s turnout as a percent of the citizen voting-age population has consistently been one of the highest across demographic groups.[51] In the 2012 election, 74 percent of eligible Black women voters turned out to vote, compared to 64 percent of white women and 45 percent of Latinx women voters.[52] Black women voters also surpassed turnout among all groups of men by at least 10 percentage points, with just 61 percent of Black men, 63 percent of white men, and 46 percent of Latinx men turning out to the polls in 2012.[53]

Although Black women’s voter turnout saw a dip in 2016 with 66 percent of Black women participating, Black women voters still exceeded turnout by every demographic group besides white women, who showed up to the polls at a rate of 67 percent.[54] In comparison, only 47 percent of Latinx women, 54 percent of Black men, 64 percent of white men, and 45 percent of Latinx men participated.[55] While 2020 turnout numbers are still being calculated, the trend of strong voter participation by Black women appears to have continued unbroken.[56]

B. Black Women Are the Democratic Party’s Most Loyal Supporters

Black women also lead all other demographic groups when it comes to their support of the Democratic Party. As political scientist Kelly Dittmar declared after analyzing two decades of voting data, “Black women voters voted for the Democratic candidates in each year at the highest levels of any gender and race subgroup.”[57] The voting habits of white women stand in stark contrast, as Ditmar explains, as white women have “voted for the Republican presidential candidate in each election since 2004.”[58]

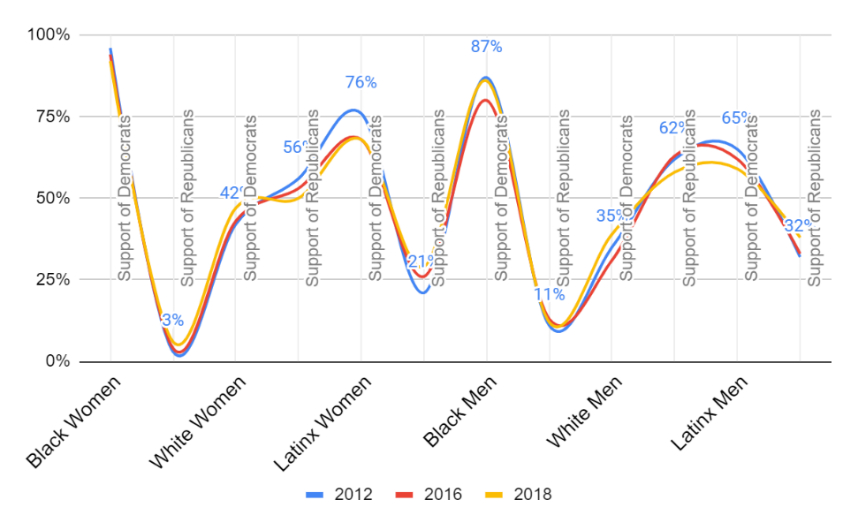

Graph II: Party Affiliation by Race and Gender[59]

Graph II: Party Affiliation by Race and Gender[59]

Although polling data from the 2020 presidential election is still being finalized, the racialized voting patterns Dittmar describes were fully on display in several of our most recent elections.[60] In 2012, 96 percent of Black women voters supported Democratic incumbent Barack Obama, compared to 42 percent of white women and 76 percent of Latinx women.[61] Black women also voted Democrat to a far greater extent than men irrespective of racial background.[62] In 2012, 87 percent of Black male voters, 65 percent of Latinx male voters, and a scant 35 percent of white male voters supported Democrats.[63]

Likewise, in 2016, Black women voted decisively in favor of Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential candidate, with less than 4 percent voting in support of then-Republican candidate Donald Trump.[64] No other demographic group’s support of the Democratic Party was similarly unequivocal. For instance, only 80 percent of Black men, 68 percent of Latinx women, and 62 percent of Latinx men supported Democratic candidates in the 2016 election.[65]

In 2016, Democratic support among white voters was even lower—with 43 percent of white women and 35 percent of white men voting for Clinton.[66] In contrast, 53 percent of white women and 63 percent of white men voted Republican and secured an electoral victory for Donald Trump.[67] However, even Black men defected from the Democratic Party at twice the frequency of Black women, with 13 percent of Black men voting Republican in 2016, compared to a mere 4 percent of Black women.[68] Defection rates among Latinx voters were even higher, with 26 percent of Latinx women and 33 percent of Latinx men supporting Republicans.[69]

In the 2018 midterm elections, Black women replicated their strong Democratic turnout, with 92 percent voting for Democratic candidates, compared to 68 percent of Latinx women and 47 percent of white women.[70] Support of Democratic candidates among male voters was modest in comparison, with 86 percent of Black men, 59 percent of Latinx men, and 39 percent of white men voting Democrat.[71] In contrast, 50 percent of white women, 58 percent of white men, 29 percent of Latinx women, 38 percent of Latinx men, and 12 percent of Black men voted Republican.[72]

Black women have also made strong showings during the primary season and in special elections. In a 2017 special election to fill the Senate seat vacated by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, Black women were credited with delivering Alabama its first Democratic Senate seat in two decades with the election of one-term Senator Doug Jones.[73] An estimated 98 percent of Black women voters supported Doug Jones in his successful bid for Alabama’s Senate seat.[74]

Black women voters also played a significant role in the election of the 46th President of the United States, Joseph Biden. Black women voters turned out to the 2020 presidential primaries with such force that Biden secured the Democratic presidential nomination, despite losing both the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary and flipping conventional wisdom about presidential primaries on its head.[75] Biden’s successful presidential run also appears to have been clinched by Black women voters in swing states like Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, who nudged him to victory in a closely contested election.[76]

Despite their long journey to obtain the franchise and their vulnerability to ongoing voter suppression tactics, Black women’s electoral force cannot be debated. Indeed, the level of participation of Black female voters relative to other demographic groups led historian Liette Gidlow to dub the legacy of the Nineteenth Amendment as producing “a Black women’s vote.”[77] Although the civic engagement of Black women voters is unrivaled, the question remains whether there is political payoff.[78]

C. Understanding Black Women Voters’ Priorities

Although Black women voters are hardly a monolith, nationwide surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019 reveal important trends when it comes to electoral policy priorities.[79] For instance, 75 percent of Black women voters surveyed in 2019 indicated that one of their key electoral priorities was ending racism and discrimination in America.[80] Black women voters also expressed overwhelming support for immigration reform, with 82 percent voicing strong disapproval for Trump’s policies on immigration and 85 percent supporting pathways to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.[81] According to polling data, Black women voters also desire robust protections for reproductive rights, including access to abortion.[82] Black women voters surveyed also identified economic opportunities, including affordable healthcare access, as a critical priority.[83]

Thus, an important question remains: Are Black women’s record-breaking levels of political participation furthering any of the aforementioned political goals?

III. Exploring the Relationship Between Black Women’s Political Participation and Political Power

In order to understand the relationship between Black women’s voting and their political power, this Article explores three common assumptions about the benefits of political participation: (1) voting is a form of civic engagement that enhances a voter’s lived reality and material well-being; (2) voting ensures that a voter’s issues are prioritized by their political party; and (3) voting preserves a status quo where the Supreme Court advances and protects important civil rights.[84] By examining the validity of each of these assumptions as they pertain to Black women voters who support Democrats, this Article attempts to gauge the true extent of Black women’s political power.

A. Assumption One: Voting Improves Black Women’s Experience of Lived Equality

The first, and perhaps simplest, assumption that underlies voting is that civic and political engagement improves the material realities of voters over time.[85] Yet, in the case of Black women, this supposition proves false.

1. Black Women Experience Heightened Economic Inequality

A staggering wage and employment gap exists between Black women and other demographic groups—one that has persisted for decades across Democratic and Republican administrations alike.[86] Black women are disproportionately likely to be unemployed or employed in positions that pay only the minimum wage.[87] In 2016, median wages for Black women who worked full time were $35,382 per year, compared to annual median wages of $43,346 for white women and $56,386 for white men—an annual difference of $7,964 and $21,004, respectively.[88] Even Black women who completed a college education were compensated several thousand dollars less on average than their white female counterparts.[89] For every dollar in earnings white men received, Black women on average are paid less than 60 cents—lost wages that could pay for food, tuition, living expenses, or health insurance.[90] Homeownership rates among Black women are also low; Black women are three times more likely than white women to be denied a mortgage.[91]

Black women also experience poverty at rates only exceeded by women in indigenous communities.[92] In 2016, 21.4 percent of Black women were living in poverty, compared to 9.7 percent of white women, and 18.7 percent of Latinx women.[93] Black women’s poverty rates also dwarfed rates of poverty among white men, which clocked in at just 7 percent.[94] In 2018, these numbers remained virtually unchanged, with 20 percent of Black women, 18 percent of Latinx women, and 9 percent of white women meeting the federal definition of poverty, compared to 7 percent of white men.[95]

Rates of poverty among Black female-headed households have been even higher over the years, hovering around 38–39 percent in 2016 and 2018, 8–10 percentage points higher than the poverty experienced by white female-headed households.[96] Even more concerning, Black women experience disproportionate rates of extreme poverty—defined as earning less than two dollars per person per day—a trend believed to be a byproduct of President Clinton’s disastrous welfare reform.[97]

Data concerning Black women’s rates of poverty are noteworthy for two reasons. First, it suggests that Black women’s political participation has little to no bearing on their material well-being, making one of the perceived benefits of voting illusory.[98] Second, it shows that political science research positing that political participation tracks voters’ affluence fails to capture the experiences of Black women voters—specifically, their dedication to participating in the political process against all odds.[99]

2. Black Women Have Reduced Healthcare Outcomes and Life Expectancies

Disparities also exist with respect to the healthcare outcomes of Black women. Black women have lower life expectancies than their white female counterparts—averaging seventy-eight years, compared to eighty-one years for white women.[100] Black women also experience higher rates of mortality than white women at virtually all stages of life. They are fifteen times more likely to be living with HIV/AIDS, and three to five times more likely (depending on age group) to die from homicide than their white female peers.[101] Maternal mortality statistics among Black women are also incredibly dire, with Black women dying during pregnancy at three times the rate of white women.[102]

Due to the barriers they face when accessing quality healthcare, Black women are more susceptible to chronic illness—a fact made all the more plain by the horrific toll of the coronavirus pandemic on Black communities in the United States.[103] Even after the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, nearly 25 percent of Black women lacked health insurance, compared to 11 percent of white women—numbers attributable, in part, to Southern states’ strong resistance to Medicaid expansion.[104]

Accordingly, although Black women vote consistently, a profound disconnect exists between Black women’s political participation levels and their material well-being.

3. Black Women Are Disproportionately Impacted by Criminalization and Mass Incarceration

Criminalization and policing also disproportionately affect Black women from an early age. For instance, Black women and girls are frequently suspended or expelled for conduct such as being “loud,” “disruptive,” or “disobedient,” while white students engage in similar behavior without fear of discipline.[105] Not only do these discrepancies in school discipline reveal racial and gender biases—often punishing Black women and girls for perceived gender non-conformity—they interfere with educational attainment by keeping the school-to-prison pipeline well-oiled.[106] One study found that, although Black women comprised less than 17 percent of all female students, they constituted 43 percent of the female school children who had experienced a school-related arrest.[107] Perhaps unsurprisingly, Black women attend college at markedly lower rates than white women, at just under 25 percent compared to 44.7 percent.[108] Even among Black women who attain bachelor’s or professional degrees, racialized wealth gaps persist.[109]

Mass incarceration also takes a heavier toll on Black women, who constitute the fastest-growing population in U.S. prisons and are twice as likely to be incarcerated as white women.[110] Though it is rarely discussed, Black women also disproportionately fall victim to police brutality and law enforcement violence, particularly when they experience mental health episodes.[111] Because criminalization trumps public health interventions as a default response, the trauma, disability, and hardship that impact many Black women and girls in the criminal-legal system are rarely addressed by the officials Black women voters elect, further highlighting the disconnect between Black women’s voting and their alleged political power.[112]

Black women experience heightened surveillance by the criminal legal system, including by social services agencies.[113] Law professor and anthropologist Khiara Bridges has written extensively about the way that child welfare laws have been weaponized against Black female-headed households as poverty is conflated with neglect, and children are seized from households for “offenses” such as lacking a warm winter coat.[114] Black mothers who rely on public benefits are also subjected to frequent drug testing and are criminalized for using drugs as innocuous as marijuana—oftentimes losing custody of their kids as a result.[115] The high rates of criminalization and policing that Black women experience also cast doubt on the thesis that voting and civic engagement materially improve the lives of Black women voters.[116]

4. The State of Black Trans Women

Black trans women as a subgroup also suffer profound forms of marginalization and exclusion, despite high voter turnout.[117] Fifteen percent of Black trans people surveyed in 2015 reported a household income below $10,000.[118] Fifty-one percent of Black transgender women are currently or formerly homeless.[119] Lifetime incarceration rates are also 47 percent among Black transgender people who, on account of the profound discrimination and social exclusion they suffer, are frequently profiled and incarcerated for poverty-related offenses like theft and survival sex work.[120] Black trans women also have reduced life expectancies, estimated to be as low as thirty-five years old.[121]

The socioeconomic status of Black transgender and cisgender women alike powerfully suggests that voting yields little to no material benefit. Black women voters lag behind their white female counterparts by every given metric, including poverty, education attainment, maternal mortality, and life expectancy.[122] These realities beg the question: To what extent does civic engagement actually matter for Black women?

B. Assumption Two: Voting Ensures that Black Women’s Issues Are Prioritized Within the Democratic Party

Another common assumption about voting and political participation is that constituents’ priorities will be taken into account when party leaders enact policies or set a legislative agenda.[123] Despite the strength of this assumption, in the case of Black women voters, little connection appears to exist.

1. The Legacy of the Clinton Presidency

Despite being dubbed the “First Black President” and cultivating broad support among Black Americans weary from the Bush and Reagan years, Bill Clinton’s presidency wreaked havoc on the Black community—thrusting record numbers of Black Americans into prison or poverty.[124] Part of the insidiousness of the Clinton presidency was Clinton’s personal mastery of doublespeak. As Michelle Alexander explains:

On the campaign trail, Bill Clinton made the economy his top priority and argued persuasively that conservatives were using race to divide the nation and divert attention from the failed economy. In practice, however, he capitulated entirely to the right-wing backlash against the civil-rights movement and embraced former president Ronald Reagan’s agenda on race, crime, welfare, and taxes—ultimately doing more harm to black communities than Reagan ever did.[125]

Clinton aggressively courted Black voters on one hand, while promising to be “tough on crime,” “end welfare as we know it,” and “Make America Great Again” on the other—twenty years before Donald Trump popularized the phrase.[126]

Once in office, President Clinton’s racial conservatism quickly won out as he signed into law the 1994 Crime Bill and sentencing laws that vastly expanded the system of mass incarceration.[127] Clinton also championed sweeping reforms that dismantled the welfare system, undermined the economic stability of countless Black families, and thrust record numbers of Black Americans into extreme poverty.[128] As political commentator Melissa Harris-Perry reported in 2008:

As Clinton performed Blackness, real Black people got poorer. The poorest African-Americans experienced an absolute decline in income, and they also became poorer relative to the poorest whites. The richest African-Americans saw an increase in income, but even the highest-earning Blacks still considerably lagged their white counterparts. Furthermore, the ‘90s witnessed the continued growth of the significant gap between Black and white median wealth.[129]

Although President Clinton forged his path to the White House on the backs of Black voters, his policies heightened their misery—revealing that even when Black women are instrumental to a candidate’s election, they rarely become a priority.[130]

2. The Legacy of the Obama Presidency

President Barack Obama’s momentous election in 2008 prompted political commentators to declare a new epoch of American racial progress. However, the impact of Obama’s presidency on Black Americans remains an open question, in part because of Obama’s own personal investment in the ideology of colorblindness.[131]

Although Black women voters fueled Obama’s historic victory—delivering the White House, accompanied by majorities in the House and Senate—Obama placed racial justice initiatives on the back burner while pursuing initiatives he attested would “look out for the interests of every American.”[132] During his first two years in office, Obama expended significant capital pursuing two such initiatives: the Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act, which expanded healthcare access for uninsured Americans, along with important Wall Street reforms.[133] However, when Republicans swept both houses in the 2010 midterm elections, Obama permanently lost his legislative mandate.[134] In essence, Obama ran out of time for Black women voters.[135]

With his legislative agenda neutered, President Obama spent much of his last year in office signing bills that renamed post offices or increased the mandate of federal law enforcement.[136] Even when Obama shifted his sights from pursuing legislation to exercising executive power, initiatives aimed at improving the lives of Black women did not garner much focus in his administration. Two of Obama’s most important initiatives—Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and a Department of Health and Human Services regulation expressly barring healthcare discrimination against transgender individuals—were principally aimed at supporting groups other than the Party’s loyal Black women voters.[137] The same can be said for My Brother’s Keeper, perhaps the only initiative rolled out by the Obama Administration that consciously centered around race.[138] The program, which devoted $200 million dollars to improving the lives of men and boys of color and providing them mentorship and employment opportunities, expressly excluded Black women and girls from participation.[139]

Although Obama’s Justice Department made some strides in the area of criminal justice reform and police accountability, the reform measures that the Obama administration pursued through agency action have been systematically unraveled by President Trump.[140] Ironically then, while one of the lessons of the Obama presidency is the enduring relevance of race—as evidenced by the backlash he faced—it did not stop President Obama from embracing the ideology of post-racialism in ways that limited the capacity of his presidency to be a lasting vehicle for racial progress, particularly in the lives of Black women.[141] The exclusion of Black women from presidential initiatives like My Brother’s Keeper also shows that, in the moments where Obama overcame his politics of racial neutrality, Black women voters were not his priority, even though their support was essential to him securing the presidency.[142]

3. Democratic President Joseph Biden’s Record on Race and Gender

Joseph Biden secured the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination and was elected the 46th President of the United States in large part due to Black women voters.[143] Yet, his record on race and gender leaves much to be desired, mirroring the impoverished record of prior Democratic presidents like Clinton and Obama.[144] As a Senator, President Biden was one of the architects of federal sentencing laws that singled out (primarily Black) crack users for mandatory prison terms and 100-to-1 sentencing disparities relative to (primarily white) cocaine users.[145] President Biden also helped author the 1994 Crime Bill, which led to an explosion in Black mass incarceration after the Clinton era.[146] Biden opposed busing initiatives aimed at integrating American schools.[147] Biden also routinely makes statements denigrating the Black community in racialized gaffes.[148]

President Biden also has a mixed record on issues related to gender. Although Biden is credited for supporting the Violence Against Women Act, he stands accused of sexually assaulting his staffer Tara Reade.[149] Biden’s sharp rebuke of Black professor Anita Hill during the 1991 confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas when he served as Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee also prevented a full vetting of her sexual harassment allegations and cleared Justice Thomas’s path to the Supreme Court.[150]

While enthusiasm for Biden among Black voters is often tepid, Biden garnered broad support from Black women primary voters who correctly judged him to be the candidate primed to defeat Trump.[151] Whether the Biden Administration’s approach to racial and gender justice will extend past mere platitudes remains to be seen. Two forces may disrupt this trend: the first is Biden’s historic selection of Kamala Harris, a woman of Black and South Asian descent, to be the nation’s first female vice president following a sustained advocacy campaign by people eager to see a Black woman represented on the ticket.[152] The second is the groundswell of support racial justice causes received from white voters following the police lynching of George Floyd, though signs suggest support for these causes may already be waning.[153]

However, pessimism about the Biden-Harris ticket also persists.[154] Drawing a through line between the presidential candidacies of Clinton, Obama, and Biden, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes: “Too often . . . in Black politics, symbolism has stood in for making a meaningful difference in the lives of Black people.”[155]

C. Assumption Three: Voting Empowers the Supreme Court to Act as a Guardian of Constitutional Democracy

Year after year, a key justification for electoral participation is the future of judicial appointments, particularly to the Supreme Court.[156] Here, the assumption appears to be that voting in presidential elections can fend off a conservative takeover of the Supreme Court and preserve the Court’s institutional role as a guardian of civil and constitutional rights.[157] This assumption falters as well because it misunderstands the status quo. Specifically, it fails to appreciate that—even prior to the confirmation of conservative ideologue Amy Coney Barrett—the Supreme Court had already abdicated its role in advancing and protecting civil rights in a manner that cannot easily be undone.[158]

1. The Supreme Court’s Open Hostility Toward Voting Rights

The Court’s decision to relinquish its role in enforcing civil rights is no more apparent than in the area of voting rights. In Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, a decision authored by now-retired liberal Justice John Paul Stevens, the Supreme Court rebuffed a challenge to Indiana’s voter identification law brought by indigent voters who argued that the state ID requirement was tantamount to a poll tax.[159] The Court acknowledged that one of the express purposes of the law was to disenfranchise voters.[160] However, applying a standard that cannot even be described as rational basis review, the Court reasoned that the law survived scrutiny because it served a secondary purpose too: “protecting the integrity and reliability of the electoral process.”[161]

Five years later in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court delivered a stunning blow to voting rights activists by dismantling one of the most important provisions of the Voting Rights Act.[162] In tandem with Section 5 of the Act, the Section 4 coverage formula deemed unconstitutional by the Court subjected nine states (including Alabama) with a demonstrated track record of voter disenfranchisement to federal oversight.[163] The Court ruled that Section 4 violated the principle of “equal sovereignty” because it subjected states like Alabama to special scrutiny based on “decades-old data” and “decades-old problems.”[164] In reaching the conclusion that supervision was no longer necessary, however, the Court disregarded a substantial body of evidence regarding the ongoing need for federal oversight over elections that appeared in the Congressional record.[165]

In the years since Crawford and Shelby County were decided, voter suppression has exploded across the country as legislators have taken the Supreme Court’s decisions in Crawford and Shelby as a permission slip to disenfranchise Black voters and other Democratic constituencies.[166] This political gamble was not accidental: since 2013, the Supreme Court has declined to engage in meaningful oversight of the electoral process even as voter suppression intensifies—delivering four losses to voting rights advocates in 2020 alone.[167] For instance, in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, the Court upheld an Ohio statute that purged duly-registered voters who failed to vote in a recent election, endorsing another powerful tool of voter suppression.[168] In Rucho v. Common Cause, the Court declared that partisan gerrymandering is outside the purview of federal courts, a decision that will have tremendous lasting significance on Black voters since racial gerrymandering and partisan gerrymandering are hard to disentangle.[169]

Given the steady creep of voter suppression laws, Black women’s strong voter turnout speaks to their determination to participate in the political process, notwithstanding the Supreme Court’s growing hostility towards disenfranchised minorities.

2. The Supreme Court’s Stagnant Jurisprudence on Racial Justice and Constitutional Torts

Voting is not the only area where the Court has shown cynicism towards racial justice and civil rights. In addition to giving plaintiffs alleging racial discrimination a heightened burden,[170] strict scrutiny has been a wolf in sheep’s clothing in the Court’s Equal Protection cases—one that the Court has used to attack initiatives aimed at remediating structural racism and inequality. The Court has repeatedly held that affirmative-action programs intended to redress historic discrimination are constitutionally suspect, but sustained them for the purpose of promoting “diversity” or non-remedial, cross-racial learning.[171] Even here, the Court has imposed strict limits: in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, the Supreme Court ruled that an initiative aimed at mass integration of Seattle-area schools with “sufficient numbers so as to avoid . . . any kind of specter of exceptionality,” violated Equal Protection and the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education.[172]

By ruling that diversity is a compelling state interest but remediation of discrimination or “racial balancing” is not, the Court has posited that the core permissible aim of affirmative action is to provide cross-racial educations to non-minority students. The Supreme Court has also gotten dangerously close to mandating a jurisprudence of colorblindness, despite the ever-present footprint of systemic racism on this country.[173]

The Court’s jurisprudence on constitutional torts has been equally rights-restrictive, due in part to the Court’s aggrandizement of qualified immunity, a judge-made doctrine that, in the Court’s own words, immunizes “all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.”[174] Pursuant to the doctrine, governmental officers who violate an individual’s statutory or constitutional rights can only be held liable for damages in cases where they “violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.”[175] But in Pearson v. Callahan, a unanimous Court ruled that judges do not have to address the legality of a defendant’s actions prior to granting immunity so long as they conclude the background law was not “clearly established.”[176] The Pearson decision continues to have significant reverberations because it has led courts to abandon their traditional function of “say[ing] what the law is” and ossified recognition of constitutional rights in many jurisdictions.[177]

The Court also expanded the footprint of qualified immunity in a series of recent cases involving victims of police brutality and unlawful law-enforcement action.[178] These decisions found that overly generalized descriptions of a constitutional right and even the slightest factual variations between precedents can be sufficient to render the law not clearly established and trigger the immunity defense.[179]

The Court has similarly immunized federal law enforcement officers from most constitutional claims by launching a frontal attack on Bivens v. Six Unknown Agents, the case in which the Court found that an implied cause of action exists against federal officials who violate the Constitution.[180] In Ziglar v. Abbasi, the Court rejected a Bivens claim brought by federal detainees challenging their conditions of confinement under the Eighth Amendment,[181] despite approving a federal prisoner’s Eighth Amendment claim nearly three decades earlier in Carlson v. Green.[182] In denying the remedy, the Court declared, “expanding the Bivens remedy is now a ‘disfavored’ judicial activity.”[183] Likewise, in Hernandez v. Mesa, the Court denied a Bivens remedy to a Mexican family whose son was shot and killed by Border Patrol officials on the ground that their Fourth Amendment seizure claim arose in a “new context.”[184]

The Court has also given a wide berth to law enforcement action in ways that have legitimated police brutality and expanded the system of mass incarceration.[185] In the past decade alone, the Supreme Court held in Plumhoff v. Rickard that officers who shot an unarmed Black motorist fifteen times acted reasonably because the motorist attempted to flee.[186] In Heien v. North Carolina, the Court authorized arrests based on “reasonable mistakes of law.”[187] Then, in Utah v. Strieff, the Court held that police officers who arbitrarily stop and frisk individuals could use any evidence recovered during an illegal search so long as an intervening act—here, a warrants check—could justify the stop.[188]

Collectively, these decisions have had the effect of ensuring that the Constitution and its guarantees are neither self-executing nor judicially enforceable.[189] For victims of police brutality and law enforcement abuses, it is difficult to see constitutional rights as more than mere words on paper.[190]

3. The Supreme Court’s Impoverished Jurisprudence on Reproductive Rights

Despite anxious commentary about the future of abortion rights and Roe v. Wade, the constitutional right to abortion has been a nullity for poor Black women since the Supreme Court’s 1977 and 1980 decisions in Maher v. Roe and Harris v. McRae.[191] In Maher, the Court upheld a state welfare regulation that denied Medicaid coverage for abortions unless a physician certified that the procedure was medically necessary.[192] Then, in Harris, the Court upheld the federal Hyde Amendment, which banned Medicaid recipients from receiving abortion care through their insurance, except in cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment.[193]

The Court openly acknowledged that these laws were intended to prevent indigent women from receiving abortions, but it was untroubled by this result. Instead, the Court voiced general support for laws restricting abortion, stating that it was permissible for legislators to “encourage[] childbirth except in the most urgent circumstances”[194] and to make “a value judgment favoring childbirth over abortion . . . by the allocation of public funds.”[195] The Court also held that states could not be expected to make up the shortfall in federal funding, effectively putting abortion out of reach for poor women.[196] Explaining its decision to turn its back on this disadvantaged group, the Court stated glibly that poverty is not a “suspect classification.”[197]

While the Court’s recent decisions in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt[198] and June Medical v. Russo[199] could be cited as a triumph of liberalism and the rule of law, they followed decisions where the Court expressed apathy about the rise of mandatory waiting periods, parental consent and notification requirements, fetus burial mandates, and other laws that inconvenience or chill abortion seekers.[200] As such, the Court has merely guarded abortion for those with the privilege and wherewithal to navigate a herculean web of state restrictions and pay for services out of pocket—a policy with pronounced racial impacts.[201] The Supreme Court’s recent decisions have also put family planning out of reach of the working poor by authorizing employers with moral objections to exclude contraception from their insurance plans.[202]

4. Shiny Baubles: The Supreme Court’s Deceptive Jurisprudence on Other Social Issues

Thanks to the growing influence of conservatism on the Supreme Court and the recent confirmation of Justice Barrett, many of the Court decisions celebrated by progressives may be Pyrrhic victories in the end.[203] For instance, although the Supreme Court has delivered victories to LGBTQ+ rights advocates in five successive cases,[204] the Court has simultaneously enlarged the religious refusal rights of companies and individuals. For instance, in Bostock v. Clayton County, a decision which found that LGBTQ+ employees were protected under laws banning sex discrimination, the Court also signaled its receptiveness to the argument that LGBTQ+ employees could lawfully be terminated due to an employer’s religious objections.[205] Then, in Our Lady of Guadalupe School, the Court held that discrimination claims brought by certain employees of religious organizations were categorically barred, casting even greater doubt on the reach of Bostock’s holding.[206]

In Little Sisters of the Poor, the Court authorized private employers to deny contraception coverage to employees based on religious and moral objections, on the heels of striking down restrictive abortion laws in June Medical.[207] In Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, the Court ordered the State of Montana to provide taxpayer-funded tuition reimbursements to religious schools, further clawing away at the doctrine of separation of church and state.[208]

And although the Supreme Court blocked the Trump Administration from dismantling DACA in 2020, the Supreme Court—including late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justices Breyer and Kagan—did not find that terminating DACA raised constitutional concerns.[209] The Court merely chided the Trump Administration for not following the proper procedure.[210] Likewise, in Department of Homeland Security v. Thuraissigiam, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, curtailed the due process rights of undocumented immigrants seeking protection from removal.[211] These decisions serve as an important reminder that even the Court’s liberal justices have shied away from demanding robust enforcement of civil and human rights. Thus, for Black women voters, supporting Democrats who can make liberal judicial appointments still offers only a limited reward.

5. Implications for Voting

Based on recent Court decisions, the assumption that voting preserves a status quo wherein the Supreme Court safeguards civil rights and democracy is simply a myth. In recent decades, little progress has been made toward advancing racial justice and police accountability—two of the issues Black women voters hold most dear—even though the Court only gained a decisive conservative majority in October 2020 following the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett.[212]

The notion that the Supreme Court will chart a new course under a Democratic president also appears to be mythical. Reversing the Court’s cynical jurisprudence on civil rights requires more than securing a coveted fifth liberal vote, since rights-restrictive decisions on qualified immunity, voting, economic justice, and corporate personhood currently blanket the field.[213] Unlocking the Court’s potential to act as a protector of civil and constitutional rights likely requires revisiting the doctrine of stare decisis in favor of a jurisprudence more willing to acknowledge judicial error—a paradigm shift that few would countenance.[214] In addition, since even “liberal” justices have been willing to deliver racial justice advocates stinging losses, it would also require applying an even greater level of partisan scrutiny to the judicial confirmation process—a move that is at odds with the air of impartiality that judges are called upon to convey.[215]

Accordingly, another key belief about voter turnout in presidential elections—namely, that it is a stopgap measure to prevent the Supreme Court as an institution from doing harm—has proven uniquely untrue in the case of Black women voters. Once more, this inevitably invites the question: Why vote at all?

IV. The Paradoxes of Black Women’s Voting: The Trapped Constituency Problem and the Caretaker Vote

Examining the socioeconomic status of Black women and the extent to which they have been prioritized by the political branches leads to a startling but inescapable conclusion: Black women’s engaged political participation bears an inverse relationship to their overall political power.[216] This Article contends this phenomenon is by design. Stated simply, Black women’s eager and enthusiastic use of the right to suffrage is paving the way for their disenfranchisement in electoral politics for two reasons: the “trapped constituency problem” and “caretaker voting.”

A. The Trapped Constituency Problem

The “trapped constituency problem” is one of the most significant challenges facing Black women voters. While the term “trapped constituency” is a unique contribution made by this Article, the phenomenon it describes is well known.[217] At the root of the trapped constituency problem is America’s two-party system where third-party voting is inviable and where one party—the Republican Party—has purposefully branded itself as the party of white identity.[218] As political scientist and gender and sexuality scholar Jane Junn explains:

There is no uncertainty about where the Republican Party stands relative to the Democratic Party on gender issues, on women’s equality issues, nor is there much misunderstanding about where the Democratic Party stands relative to the Republican Party in terms of race.[219]

Stated another way, Black women “understand that they have nowhere to go other than Democratic candidates, even if they’ve got to hold their nose to do so.”[220] As the trapped constituency thesis contends, the political establishment also appreciates that Black women lack viable alternatives. Therefore, in any given election year, Democratic Party officials can feel confident that Black women will not defect from the Party in any meaningful numbers.[221]

By virtue of the trapped constituency problem, not only are Black women’s electoral concerns deprioritized within the party to whom they remain loyal, Democrats are free to direct their resources to courting coveted “swing voters”—a group that, on the whole, trends white and conservative—in ways that diminish Black women’s power.[222] Once Democratic presidents take office, Black women’s priorities frequently yield due to the perceived lack of consequence for these moments of political abandonment.[223]

B. Black Women and the Caretaker Vote

Even Black women voters who grasp the fullness of their status as a trapped constituency continue to vote in ways that safeguard the rights of others while threatening their own political power.[224] I have coined the phrase “caretaker voting” to describe this behavior.

While Black women voters have rightfully decried the notion that it is their duty to “save America from itself,” their voting habits suggest otherwise. Rather than voting primarily to advance their self-interest, Black women appear to be voting with the welfare of a much larger polis in mind—American democracy itself—motivated in part by their own experiences of navigating racism, misogyny, and bias.[225] Black women’s voting habits in the 2016 and 2020 elections offer a clear example of caretaker voting.[226] In each election, Black women consolidated their support around Democratic candidates with obvious flaws to block what they perceived as a greater evil—a Donald Trump presidency.[227] Black women also flooded the polls in 2012 to stave off a Mitt Romney presidency and preserve legislative victories like the Affordable Care Act, all while overlooking the ways Black women were ultimately sidelined by the Obama Administration.[228]

Explaining these voting habits in a poignant op-ed, Reverend Renita Weems writes: “Voting allows us [Black women] to marshal our agency to love ourselves, to write our own history, and to use our anger in the service of hope for a better world.”[229] However reluctantly, Black women have assumed the role of caretaker for American democracy.

How do we overcome this phenomenon of caretaker voting? The answer is not adopting a politics of self-interest that makes Black women lose the distinction of being highly empathetic, multi-issue voters. Instead, the solution lies in disrupting the powerlessness that Black women voters face by abandoning the model that equates voting with self-sacrifice.

V. Not Your Mule: Answering the Trapped Constituency Problem

Although the trapped constituency problem and caretaker voting are formidable challenges that work in tandem to limit Black women’s political power, an important avenue exists for Black women to reclaim power: becoming proverbial “swing voters” whose loyalty must be earned election after election. Devising strategies for Black women to become swing voters within the confines of a racialized two-party system is no easy feat. However, instead of hinging swing voting on the non-credible threat that Black women intend to join the Republican Party en masse, Black women can act like swing voters by placing their voter turnout in jeopardy. There are four key aspects of this swing-vote strategy.

First, since Black women’s electoral power is at its zenith in presidential primaries, an initial strategy could be lobbying candidates ahead of the primaries and hinging votes on articulated demands.[230] For instance, voters could demand the inclusion of certain policies on a candidate’s platform or interrogate their positions on key racial justice issues, forcing candidates to sharpen and refine their racial justice and gender justice commitments ahead of Democratic primaries. Black women voters could direct their votes to the primary candidates who demonstrate the strongest social justice bona fides, rather than the person deemed most electable, forcing candidates to compete against one another with respect to their credentials. This would help to overcome the trapped constituency problem because it would mean that only candidates committed to making lived equality a reality for Black women would advance to the general election.

Second, deepening the tradition of Black feminist organizing, Black women voters could continue their political engagement after elections to make sure electoral promises made are executed. The Black Futures Lab, originated by Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza, describes one aspect of this work as “mobilizing voters year-round and building relationships with candidates on our own terms.”[231]

Third, and perhaps most significantly, Black women voters overlooked by the political establishment could consider staging a protest non-vote—that is, publicly refusing to vote in national elections where candidates refuse to prioritize Black voters’ needs. To ensure that protest non-voting would not be mistaken for voter apathy, such as the across-the-board drop in turnout in 2016, voters who pursue this strategy would need to clearly announce their tactics and intentions in advance. Ideally, this would entail Black women voters collectively signing on to a pledge or platform that explains their votes are being strategically withheld until Black women’s needs and demands are prioritized. Black women could also try to redirect their civic engagement work to issue-organizing and local elections in the interim.[232]

In a year that has been marred by the twin pandemics of Covid-19 and racialized police violence—one where the enduring realities of systemic racism have been laid bare—important conversations about the Democratic Party’s relationship to Black voters are already taking place.[233] Black women voters have begun interrogating the assumptions that led prior generations to dutifully vote for Democrats who ignored or demeaned them, and Black women voters are increasingly making their own demands of the political system.[234] One prominent demand—to add a Black woman to the presidential ticket—was resoundingly answered when Joe Biden added Kamala Harris to his ticket as vice president.[235] Harris’s selection as the nation’s first female vice president is thus a case study on the power that Black women can wield when they couple their voting with political demands—albeit, a strategy that could benefit from refining to place greater emphasis on policy priorities.[236]

Calling on Black women to become a “swing voting bloc” whose turnout depends on the quality of a candidate and their political platform seems a logical next step.[237] Yet, articulating a strategy for Black women voters to become “swing voters” in a highly contested election year inevitably prompts questions and perhaps even skepticism. This is especially true on the heels of the 2020 elections, which served as a referendum on, and rebuke of, Donald Trump—albeit by a razor’s edge.[238] Herein lies the fourth and final strategy articulated by this Article: “exceptional circumstances.” Exceptional circumstances voting accommodates election years like 2020 where the argument for voting Democrat is especially compelling due to the perceived costs of nonparticipation, even if voters’ concerns have not been meaningfully prioritized. Black women voters who find themselves in this situation can draft and sign onto a national pledge that explains their decision to engage in caretaker voting, their expectations of the Democratic Party and candidates going forward, and their commitment to withdraw support in future elections if their policy demands are ignored.[239] That way, Black women voters can respond to urgent “all hands on deck” political moments without engaging in the same cycle of caretaker voting that leads Black women’s political priorities to be sacrificed year after year, along with their overall well-being.[240]

Conclusion

Although Black women have fought hard to realize the promise of the Nineteenth Amendment and grown into an electoral force that votes at incredible odds, the fruits of this labor have yet to materialize for voters themselves. Ironically, Black women’s faithful and unwavering support for the Democratic Party in recent years has led them to become “trapped constituents” whose votes are largely taken for granted by the political establishment. As a consequence, Black women’s political participation has come to bear an inverse relationship to Black women’s socioeconomic and political power in ways that challenge conventional wisdom about voting. This Article argues that Black women should disrupt this trend by proliferating strategies—including non-voting—that put them on equal footing with traditional swing voters.

It is unclear whether the swing voting strategies I identify here will gain widespread traction. If they fail to do so, it may be a result of the continued pull of the precise forms of caretaker voting described in this Article—voting habits that lead Black women to act as the guardians of American democracy, time and again. Yet, as this Article has illuminated, Black women’s tendency to prioritize the well-being of the collective over their own political goals is a costly strategy: one that allows all three branches of government to turn their backs to Black women’s concerns.

Without putting Black women’s voter turnout into issue, Black women’s electoral taken-for-grantedness will persist in ways that continue to threaten their welfare as well as their political power. The swing vote strategy articulated here disrupts this cycle of powerlessness. By conditioning voting on the quality of the Democratic Party’s platforms and making election turnout something Democratic candidates must earn, Black women voters have “nothing to lose but our chains.”[241]

*Legal Scholar and Senior Attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights. Special thanks to Nicole Humphrey, Dorian Boncoeur, and Kelechi Ezie, who shared invaluable advice and comments.

- U.S. Const. amend. XIX. ↑

- See Jennifer K. Brown, The Nineteenth Amendment and Women’s Equality, 102 Yale L.J. 2175, 2177–81 (1993) (summarizing the history of the Nineteenth Amendment, from the 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls to its ratification in 1920). ↑

- Another Amendment Ratified, N.Y. Times, Aug. 19, 1920, at 8. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See infra Section I.B. ↑

- Kamala Harris’s historic selection as the nation’s first female vice president can be understood as a response to these historical trends. See discussion infra Part V. ↑

- See infra Parts II, III, and IV, for an in-depth exploration of these arguments. ↑

- See infra Section III.A. ↑

- See infra Section III.A. ↑

- See infra Section III.B and Part IV. ↑

- See infra Part III. ↑

- See infra Part IV. ↑

- See Liette Gidlow, More than Double: African American Women and the Rise of a “Women’s Vote”, 32 J. Women’s Hist. 52, 53 (2020). ↑

- See John E. Filer et al., Voting Laws, Educational Policies, and Minority Turnout, 34 J.L. & Econ. 371, 373 (1991) (noting that poll taxes were also due by deadlines Black voters were rarely advised of). ↑

- See id. at 374. ↑

- See id. at 374, 387–89 (tracking the impact of literacy tests on Black voter turnout); Gidlow, supra note 13, at 55–56. ↑

- See United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214, 220–21 (1876). ↑

- See id.; see also Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide 32–37 (2016) (explaining that Reese formed part of a disastrous series of Supreme Court cases that rendered the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments a virtual nullity). ↑

- See Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213, 222 (1898) (noting that a stated goal of the poll tax was to “obstruct the exercise of suffrage by the negro race”) (citation omitted); see also Anderson, supra note 18, at 35 (demonstrating that animus towards Black voters motivated the poll tax’s adoption). Interestingly, as poll tax laws expanded, poor white Southerners also became a casualty. According to a 1943 survey, over 6.8 million white voters were disenfranchised across the South as a result of poll tax laws, compared to at least 4 million Black voters. See William M. Brewer, The Poll Tax and Poll Taxers, 29 J. Negro Hist. 260, 265 (1944), for the total of “Whites Disfranchised” and “Colored People Disfranchised.” ↑

- See Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903); Giles v. Teasly, 193 U.S. 146 (1904). ↑

- See Anderson, supra note 18, at ch. 2. ↑

- See, e.g., Breedlove v. Suttles, 302 U.S. 277 (1937) (upholding Georgia poll tax applicable to both women and men); Lassiter v. Northampton Cnty. Bd. of Elections, 360 U.S. 45 (1959) (upholding North Carolina’s use of a literacy test). ↑

- See Gidlow, supra note 13, at 54–55. ↑

- Darlene Clark Hine, Blacks and the Destruction of the Democratic White Primary 1935-1944, 62 J. Negro Hist. 43, 43 (1977). ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U.S. 45, 55 (1935) (initially upholding Texas’s white primary); Smith v. Allright, 321 U.S. 649, 661–62 (1944) (overruling Grovey and holding that primaries were subject to scrutiny under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments); Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461, 470 (1953) (finally barring all-white primaries in all their forms); see also Robert B. McKay, Racial Discrimination in the Electoral Process, 407 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. & Soc. Sci. 102, 106–07 (1973) (describing the long half-life of white primaries in states like Texas); Ellen D. Katz, Resurrecting the White Primary, 153 U. Pa. L. Rev. 325, 332–50 (2004) (tracking history of legal challenges). ↑

- Gidlow, supra note 13, at 56. ↑

- Tara McAndrew, The History of the KKK in American Politics, JSTOR Daily (Jan. 25, 2017), https://daily.jstor.org/history-kkk-american-politics/ [https://perma.cc/7XF6-RADN]; Gidlow, supra note 13, at 54–55 (describing the Klan revival in Jacksonville, Florida). ↑

- For instance, although Black people comprised just 10 percent of the U.S. population in 1940, they constituted approximately 35 percent of the population in Alabama, Louisiana, and Georgia; 43 percent of the population of South Carolina; and just under 50 percent of the population of Mississippi. Campbell Gibson & Kay Jung, Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States tbls.1, 15, 25, 33, 39 & 55 (U.S. Census Bureau, Working Paper No. 56, 2002), https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2002/demo/POP-twps0056.pdf [https://perma.cc/7D4Q-8ZUT]. ↑

- See Gidlow, supra note 13, at 56–59. ↑

- See, e.g., Brent Staples, Opinion, How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women, N.Y. Times (July 28, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/28/opinion/sunday/suffrage-movement-racism-black-women.html [https://perma.cc/L6BW-5E5H]; Phillip N. Cohen, Nationalism and Suffrage: Gender Struggle in Nation-Building America, 21 Signs 707 (1996); Steven Mintz, The Passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, 21 OAH Mag. Hist.: Reinterpreting the 1920s 47, 47–48 (2007); Lynn Dumenil, The New Woman and the Politics of the 1920s, 21 OAH Mag. Hist.: Reinterpreting the 1920s 22, 22 (2007). But see Dasha Matthews, Ida B. Wells: Suffragist, Feminist, and Leader, UMKC Women’s Ctr. (Feb. 21, 2018), https://info.umkc.edu/womenc/2018/02/21/ida-b-wells-suffragist-feminist-and-leader/ [https://perma.cc/YM64-DBAH] (noting the important contributions of Black women suffragists like Ida B. Wells). ↑

- See, e.g., Gidlow, supra note 13, at 58; Dumenil, supra note 31, at 22; Staples, supra note 31. ↑

- Gidlow, supra note 13, at 58–59 (citing the National Women’s Party and the League of Women Voters as examples of prominent women’s rights organizations that eventually turned their backs on Black women voters); see also Dumenil, supra note 31, at 24 (discussing the fractures in the female community after ratification). But see Anita Shafer Goodstein, A Rare Alliance: African American and White Women in the Tennessee Elections of 1919 and 1920, 64 J. S. Hist. 219, 219–22 (1998) (describing a rare period of cross-racial voter rights organizing in Tennessee). ↑

- Katherine Blee, Women in the 1920’s Ku Klux Klan Movement, 17 Feminist Stud. 57, 58 (1991); see also JR Thorpe, How the Fight for Women’s Voting Rights Actually Benefitted White Supremacy, Bustle (Aug. 18, 2017), https://www.bustle.com/p/white-supremacy-benefitted-from-womens-suffrage-the-impact-is-still-felt-today-76420 [https://perma.cc/3TBA-QVGZ]. ↑

- Goodstein, supra note 33, at 238. ↑

- Gidlow, supra note 13, at 58. ↑

- See Blee, supra note 34, at 58, 72. ↑

- See infra Part II for a discussion of women’s voting habits. ↑

- See Anderson, supra note 18, at 22–24. ↑

- Id. at 19–20. Though Black Codes varied state to state, they included prohibitions on vagrancy, “disobedience or imprudence,” and a requirement that newly emancipated Black people obtain employment as plantation laborers or domestics or face criminal punishment. Id. ↑

- Gidlow, supra note 13, at 54–55, 59. ↑

- Anderson, supra note 18, at 32–37 (discussing the long line of cases that were regressively decided and joined by Republican-nominated justices and noting Republican Justice Joseph Bradley’s open contempt towards Black litigants seeking the Court’s protections). ↑

- Gidlow, supra note 13, at 57. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. (citing Glenda E. Gilmore, False Friends and Avowed Enemies: Southern African Americans and Party Allegiances in the 1920s, in Jumpin’ Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights, 219, 222 (Jane Daily, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, & Bryant Simon, eds., 2000). ↑

- Gidlow, supra note 13, at 55–56. ↑

- Jerry DeMuth, Fannie Lou Hamer: Tired of Being Sick and Tired, Nation (June 1, 1964), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/fannie-lou-hamer-tired-being-sick-and-tired/ [https://perma.cc/9SUC-73HB]. ↑

- Margalit Fox, Amelia Boynton Robinson, a Pivotal Figure at the Selma March, Dies at 104, N.Y. Times (Aug. 26, 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/27/us/amelia-boynton-robinson-a-pivotal-figure-at-the-selma-march-dies-at-104.html [https://perma.cc/T4UN-5S5A]. ↑

- Voting Rights Act of 1965, 52 U.S.C. §§ 10101–30146; see also Chandler Davidson, The Voting Rights Act: A Brief History, in Controversies in Minority Voting 7, 21 (B. Grofman & C. Davidson eds., 1992) (“[I]n the five years after [the VRA’s] passage, almost as many Blacks registered [to vote] in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and South Carolina as in the entire century before 1965.”); Gilda R. Daniels, Racial Redistricting in A Post-Racial World, 32 Cardozo L. Rev. 947, 951, 951–56 (2011) (describing the operation of the Voting Rights Act and dubbing it “one of the most effective pieces of legislation in this country’s history”). ↑

- This graph was created by the author using data from Danyelle Solomon & Connor Maxwell, Women of Color A Collective Powerhouse in the U.S. Electorate 29 (2019), https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2019/11/18120343/Women-of-Color-in-the-American-Electorate.pdf [https://perma.cc/ZF26-2RD4] [hereinafter Solomon & Maxwell, Women of Color], and Ctr. for Am. Women & Pol., Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, Gender Differences In Voter Turnout 2 (2019), https://cawp.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/resources/genderdiff.pdf [https://perma.cc/Z63Y-PQJT] [hereinafter Ctr. for Am. Women & Pol., Gender Differences]. ↑

- See supra Graph I. ↑

- Solomon & Maxwell, Women of Color, supra note 50, at 29 (tracking voting patterns of women). ↑

- Ctr. for Am. Women & Pol., Gender Differences, supra note 50, at 2 (providing data regarding turnout by men). ↑

- See Graph I (citing Solomon & Maxwell, Women of Color, supra note 50, at 29). ↑

- See Graph I (citing Ctr. for Am. Women & Pol., Gender Differences, supra note 50, at 2). ↑

- Erin Delmore, This Is How Women Voters Decided the 2020 Election, NBC News (Nov. 13, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/know-your-value/feature/how-women-voters-decided-2020-election-ncna1247746 [https://perma.cc/QM6D-6FJ7]. ↑

- Kelly E. Dittmar, Women and the Vote: From Enfranchisement to Influence, in Minority Voting in the United States 99, 110 (Kyle L. Kreider & Thomas J. Baldino eds., 2015) (citations omitted). ↑

- Id. ↑

- This graph was created by the author using data from Maya Harris, Women of Color: A Growing Force in the American Electorate (2014), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2014/10/30/99962/women-of-color/ [https://perma.cc/78LA-W4SC]; Stanley Feldman & Melissa Herrmann, CBS News Exit Polls: How Donald Trump Won the U.S. Presidency, CBS News (Nov. 9, 2016), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cbs-news-exit-polls-how-donald-trump-won-the-us-presidency/ [https://perma.cc/3G5P-DC58]; Whitney Blake, The GOP Can Attract Young Black Voters—And Already Has, Wash. Examiner (Aug. 12, 2014, 7:20 AM), https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/the-gop-can-attract-young-black-votersand-already-has# [https://perma.cc/N6QH-TTBZ]; John Cassidy, What’s Up with White Women? They Voted for Romney, Too, New Yorker (Nov. 8, 2012), https://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/whats-up-with-white-women-they-voted-for-romney-too [https://perma.cc/67SN-P7AS]; Holly K. Sonneland & Nicki Fleischner, How U.S. Latinos Voted in the 2016 Presidential Election, Am. Soc’y Council of Ams. (Nov. 10, 2016), https://www.as-coa.org/articles/chart-how-us-latinos-voted-2016-presidential-election [https://perma.cc/BZY9-74HX]; Jessica Lavariega Monforti, The Latina/o Gender Gap in the 2016 Election, 42 Aztlan; J. Chicano Stud. 229, 238, 240, 245 (2017), http://mattbarreto.com/mbarreto/courses/lavariega_aztlan.pdf [https://perma.cc/97Z5-NAFD] (citing pre-election polling data which may be less reliable); How We Voted in the 2018 Midterms, Wall St. J. (Nov. 6, 2018, 11:30 PM), https://www.wsj.com/graphics/election-2018-votecast-poll/ [https://perma.cc/P2VC-KJ7Z]. ↑

- See supra Graph II. ↑

- Harris, supra note 59. ↑

- See generally Graph II. ↑

- Feldman & Herrmann, supra note 59 (reporting on white male voting habits); Harris, supra note 59 (reporting on voting by other groups). ↑

- Feldman & Herrmann, supra note 59. ↑

- Id.; see also Sonneland & Fleischner, supra note 59. ↑

- Feldman & Herrmann, supra note 59. ↑

- Id.; see also Katie Rogers, White Women Helped Elect Donald Trump, N.Y. Times (Nov. 9, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/01/us/politics/white-women-helped-elect-donald-trump.html [https://perma.cc/Z2G3-99MR]; Lorrie Frasure-Yokley, Choosing the Velvet Glove: Women Voters, Ambivalent Sexism, and Vote Choice in 2016, 3 J. Race, Ethnicity & Pol. 3, 3–19 (2018) (attributing white women’s support of Trump to racial resentment and ambivalent sexism). ↑

- See Feldman & Herrmann, supra note 59; see also Jane Coaston, The Gender Gap in Black Views on Trump, Explained, Vox (May 9, 2020, 12:30 PM), https://www.vox.com/2020/3/9/21151095/black-women-trump-gop-conservatism-gap-2020 [https://perma.cc/4D7P-8QRY] (explaining that a gender gap between Black voters continues to persist regarding Trump). ↑

- See Feldman & Herrmann, supra note 59; Sonneland & Fleischner, supra note 59. ↑

- How We Voted in the 2018 Midterms, supra note 59. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑